For years, millions of Indonesians across the vast archipelago watched the same movie on the last day of September. The Treachery of the September 30 Movement/PKI inculcated in a generation the founding myth of the Suharto regime: that in 1965 the courageous army worked with patriotic civilians to defeat a brutal communist takeover.

In fact, the estimated one million victims of the political genocide of 1965-66 were virtually all killed for non-violent political participation in groups for farmers, writers, workers, or women; for being ethnically Chinese; or simply to settle scores. Survivors faced lifelong restrictions in voting, education, and employment, and even their grandchildren face discrimination. A half-century after the killings and 15 years after the fall of the President Suharto, no perpetrators have been held accountable.

This year, however, September 30 was marked by the free, online release of a remarkable corrective to the propaganda many Indonesians were raised on. Several years ago, an American named Joshua Oppenheimer began filming victims and their families. His subjects encouraged him to interview the perpetrators living among them, confident they would speak freely, even proudly, about their role in the killings.

The result is the documentary, The Act of Killing, which has profoundly impacted audiences at film festivals and art houses around the world over the last year. Filling in as anchor of the The Daily Show, John Oliver told Oppenheimer, "It took me two hours to watch and about three days to get over . ... I've thought about it every day since I saw it."

Although the documentary is ultimately about much more than the violent past of one country, its impact may be most significant inside Indonesia. Can a documentary help transform the political and social landscape of a country held prisoner by a violent, unexamined past? After a discussion of the film, this post considers the promise and the limits of the film's impact.

The Film

Anwar Congo is a loving grandfather, a charming, dapper white-haired man in the autumn of his life. In 1965 and 1966, Anwar killed as many as 1,000 people in the North Sumatran city of Medan, using a length of wire and a piece of wood. (He explains, "At first we beat them to death. But there was too much blood.")

In 1965, Anwar and his friends were preman bioskop, small-time gangsters who scalped tickets while planning crimes from a base at a movie theater. When the killings started, their death squad began operations on a nearby rooftop, borrowing methods and styles from the gangster movies, and even the Elvis vehicles, that they had just watched across the street. Violence and performance were intertwined from the very beginning in a never-ending cycle of tragedy and farce.

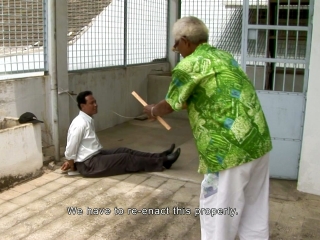

As Oppenheimer filmed the process with Christine Cynn and an Indonesian co-director (listed as Anonymous due to fear of reprisals), the perpetrators wrote, directed and performed recreations of the killings in the genres they loved: a western, a gangster movie, a musical. (Oppenheimer describes how the reenactments came about here).

As Oppenheimer filmed the process with Christine Cynn and an Indonesian co-director (listed as Anonymous due to fear of reprisals), the perpetrators wrote, directed and performed recreations of the killings in the genres they loved: a western, a gangster movie, a musical. (Oppenheimer describes how the reenactments came about here).

The result is a glimpse into how Anwar and Indonesia -- and the rest of us -- use myth, imagination, and denial to make the past tolerable to the conscience. Long unchallenged by other narratives, the killers build and maintain absurd versions of the past: in a garish and dreamlike musical number set in heaven, a victim thanks Anwar for his own execution.

It's shocking, but that very overreach may be the most effective way to tear down decades of myth-making. You can't defeat propaganda with more propaganda, or even always with the truth, but you can use it against itself.

The reenactments even begin to produce cracks in the perpetrator's own walls of denial and forgetting. Anwar cuts short a film noir reenactment where he plays a victim. A scene in which the paramilitary attacks a village (filmed a few hundred yards from a mass grave, the director later learned) creates a degree of fear and emotion that persists long after the actor/director/gangster Herman yells "Cut!" A final scene on the rooftop drives home the degree to which Anwar's actions have taken a toll on him.

The reenactments even begin to produce cracks in the perpetrator's own walls of denial and forgetting. Anwar cuts short a film noir reenactment where he plays a victim. A scene in which the paramilitary attacks a village (filmed a few hundred yards from a mass grave, the director later learned) creates a degree of fear and emotion that persists long after the actor/director/gangster Herman yells "Cut!" A final scene on the rooftop drives home the degree to which Anwar's actions have taken a toll on him.

Oppenheimer emphasizes that the film is actually about the present, not the past. In his note to Indonesian viewers he explains that he and his anonymous Indonesian colleagues wanted "to understand how impunity for past atrocities underpins a present day regime of corruption, thuggery, and terror."

Oppenheimer emphasizes that the film is actually about the present, not the past. In his note to Indonesian viewers he explains that he and his anonymous Indonesian colleagues wanted "to understand how impunity for past atrocities underpins a present day regime of corruption, thuggery, and terror."

The implications of the film extend subtly across borders as well as decades. Oppenheimer has told interviewers that the controversial decision to render a mass killer in a humane, nuanced way serves to uncomfortably narrow his distance from the viewer: "by identifying with Anwar, audiences are forced to confront the fact that we are all much closer to perpetrators than we would like to believe." Our normality is also built on a foundation of violence and lies, from Abu Ghraib to the factory floors of Bangladesh.

The Release in Indonesia

Victims and human rights advocates have struggled for years to undo the myths of 1965. There have been more than a dozen movies with testimony by victims and experts on the killings, and last year an 850-page report by Indonesia's National Commission on Human Rights found the killings to be a gross violation of human rights. They recommended army officials be investigated for rape, torture, murder and other serious crimes; the Attorney General sent back the report without acting.

The Act of Killing is something different, in form and impact on audiences. Before it was released online, there were a thousand underground screenings and discussions across Indonesia. The film prompted an unprecedented cover story on "Executioners' Confessions" from around the country in the magazine Tempo, as well as other stories on the legacy of 1965 by CNN and Al Jazeera.

In a 2012 article, Indonesian sociologist Ariel Heryanto, an expert on the impact of the 1965 violence on Indonesian public life, looked forward to a wider release of the film, anticipating the irony: "that the nation's biggest and most atrocious deception is being ripped apart... courtesy of a bunch of boastful killers that many of us would love to hate."

Instead of submitting the film to Indonesian censors for release in theaters (which might have become targets of violence), the director worked with Drafthouse Films, VICE, and VHX to make the director's cut available for free download in Indonesia.

In the first week the filmmakers counted about 6,500 downloads, two-thirds of them outside the capital; they have also made available 1,000 DVDs. Oppenheimer's goal is to spark conversation, as he explained in an email: "We have always wanted people to watch the film together, in groups, and to discuss it. ... To imagine solutions requires collective dialogue. And the struggles for change will also need to be collective."

Many observers consider The Act of Killing and the debate it has provoked as a turning point in Indonesia's political life. In a recent email about the online release, Andreas Harsono, a veteran journalist and a consultant to Human Rights Watch, expressed confidence that the film "will bring the discussion of the 1965 massacre to a new level in Indonesia. It will gradually change the narrative of the 1965 killings."

Usman Hamid, a human rights activist who heads Change.org's branch in Indonesia, told me the film is slowly going viral in Indonesia, helped in part by the demand to get into underground screenings over the past year.

While some viewers have pointed out gaps in the film concerning the political context, the victims, and the role of the army, for Usman the film is so effective because it leaves many questions unanswered. In the absence of a straightforward narrative structure, viewers are left to wonder:

how seemingly normal men could do such heinous things and then go unpunished, and about the political context and the role of the international community, including the CIA. The gaps and ambiguities provoke conversation among everyone, and particularly younger Indonesians who are more used to active engagement with the world through technology. ... This movie didn't tell you where you have to take a stand. It's up to you. Why and what do you want to do? It makes people start to learn and talk and have a conversation.

Usman believes next year's elections will mark a generational change for voters and leaders. But a first-time voter in 2014 was born in the last full year of Suharto's reign, and even many older voters will have limited memories of his 30-year regime, let alone the 1965 killings it was founded upon. Usman says, "The Act of Killing demolishes their understanding, memory, feelings, their views about everything. Even about their own middle class, apolitical positions." The crimes of the past are not abstract notions: among the candidates for president are former generals linked to crimes against humanity and forced disappearances.

At the same time, some observers feel that their admittedly high expectations for the film's impact have not been met. At an August conference in Melbourne called "After The Act of Killing," the sociologist Ariel Heryanto tempered his earlier optimism. He is a fan of the film, calling it a masterpiece that profoundly affected him and many others. But he is no longer so confident it will radically alter Indonesia's political life or perspective of the past.

Heryanto speculated that Indonesia's "moral and political deficits" may be even worse than they appear onscreen. The lack of a political controversy on the scale he hoped for only underscores the film's argument, serving as a

most obscene testimony to the absolute impunity enjoyed by political gangsters who have run the country for nearly half a century. ... If Indonesians are not reacting like their international counterparts, the reason is not fear in expressing themselves, but because news about gangsterism, criminal behavior, boasting and impunity is all too common.

In the end, Heryanto's position is fully consistent with the filmmakers and others who want to see change come to Indonesia, but recognize a dogged, realistic approach is needed. As Oppenheimer told me in an email, "A film cannot change a country -- it can only create a space for the people who see it to discuss the nation's most painful and important problems without fear, and for the first time."

In an interview with Film Comment Oppenheimer explained more fully how a mix of optimism and pessimism was actually essential to his work:

The point of art is to unsettle people. And therefore there has to be pessimism or you're not, for me, making art. But why do I make this? How could I do this for seven years? Because somehow some other part of me is optimistic. It'll do something. It'll touch people. And it'll make real change in Indonesia, and it's already starting to, and that double movement between optimism and pessimism is the only way.

And because the film is not just about 1965, or about Indonesia, the rest of us are also left to wrestle with our culpability and the stories we create about the past, caught between despair and hope, tragedy and farce, pessimism and optimism.

Photo credits: Drafthouse Films