Only rarely can a documentary match feature films for gripping human drama, but this one, The Two Escobars, has more than done that. Its two illustrious characters, born into unrelated Medellin families named Escobar, captivated the nation of Colombia for several years (ending in 1994) and shook its laissez-faire roots. Now their story captivates us. The 100-minute film premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival April 22, and it will show Friday, May 14, at the Cannes Film Festival that begins this week. It is an official selection in Cinema de la Plage.

This story of ill-gained power turned loose on soccer was directed by brothers Jeff and Michael Zimbalist (Favela Rising, TFF '05). It traces the lives of Pablo Escobar, who rose to become Colombia's #1 drug lord and soccer supporter, and Andres Escobar, who, as inspirational team captain, helped produce a great national soccer team that unified the country. Neither would have had as much influence on reshaping their country had their lives not become entwined. But they did, and this combination created a saga of Shakespearean proportions that brought their country both blood and glory that would not last.

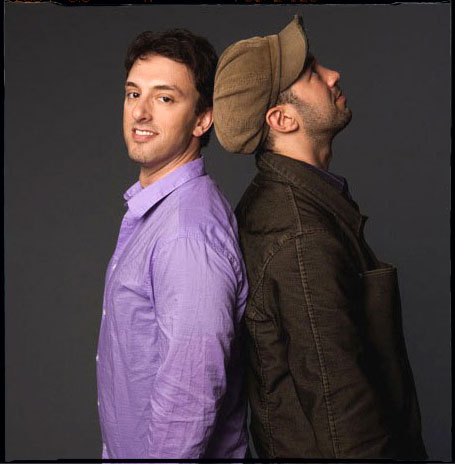

Michael and Jeff Zimbalist / Portrait by Leslie Hassler

The Zimbalists reveal the paths of these men through archival film and current interviews with family and key informants. We finally learn why Colombia's government allowed drug cartels free reign for so long, destroying the country's international reputation. Pablo's illicit career began in the '70s, when his youthful Robin Hood convictions were to help the poor by any means necessary. Jeff says: "By the '80s, his values and convictions began to mutate. The more infamous he became, the more dangerous his life became. He turned to more desperate measures."

Protecting his turf from rivals and issuing paybacks, Pablo ordered killings as dispassionately as ordering coffee. At the same time, he built soccer fields for small towns far and wide. During his ascent to power (and descent into hell), he and two rival drug lords began laundering their millions through the National Soccer Federation, thus birthing the term "Narco-soccer." The federation's top officials were knowingly complicit in this illegal relationship and later paid with jail time. Pablo supported the Medellin team on which Andres played, and the Nacionale team Andres later joined, yet Andres and his team were never told where their money was coming from. Most strongly suspected Pablo was behind the sudden rise in their fortunes but everyone followed a 'don't ask, don't tell' policy. New equipment, coaches and higher salaries meant the better players stayed and good foreign talent was hired. The team's skills improved rapidly. And Andres' honorable goals inspired his team. He wanted to popularize soccer so kids would want to play and keep off drug-infested streets. At that time, Colombia offered very few options for its youth. So he established soccer clinics and a soccer scholarship.

During the late '80s and early 90s, the Nacionale team began to rise. Large bets were placed. National attention grew with each win, and the crowds grew more excited. In 1993, Andres' team played 26 games, losing only one. Heroes were born. Soccer's greatest, Pele, came from Brazil to see them play. They moved on to play international teams and won or tied most or all or them. Finally, in order to quality for the World Cup, they would have to beat the great Argentine team, two-time World Cup winners. Playing magnificently, they defeated the Argentine team 5-0 on its home field, after which the Argentinian crowd gave them a standing ovation. They had qualified for the 1994 World Cup. At this point, the film reaches a very exciting, sordid, and extended climax that should not be revealed if you want the maximum emotional experience. The directors' advice is the same. Don't read too much about this film before seeing it!

The characters are large enough to move the direction of an entire country. After Pablo killed more than 5,000 people with bombs and made his country a universal menace, he was the devil to the law-abiding. But to the vast poor, he was an angel . During his reign, he bought them homes and fed them. And his money was improving aspects of the country. Arresting Pablo would have meant riots on a grand scale. On how the film treats Pablo, Jeff said: "We didn't want to put a filmmaker's judgment on Pablo. We didn't live through those times. We just wanted to create a very balanced portrait for both sides."

When the U.S. wanted him extradited, Pablo threatened legislators with the question "Silver or lead?" (money or a bullet?) forcing them to strike Colombia's constitutional law allowing extradition. He had said, "Better die on Colombian soil than rot in a U.S. prison." By this method, he never faced trial in the U.S. Pablo's bullying continued until U.S. President George H.W. Bush insisted Colombia's president stand up to him and sent special forces. By this time, Pablo's noose was tightening. He was killed in December, 1993, but it wasn't at the hand of either government.

How did you come to find and tell this story?

Michael: ESPN approached us to be one of 30 documentary filmmakers making films for their 30th anniversary series called 30for30. They wanted stories showing how sports influenced society and vice versa over the past 30 years. They wanted a story from South America and knew of our 2005 South American film Favela Rising, which won 37 international awards. We asked around for ideas, and a colleague, Nick Sprague, suggested the amazing overlaps between these two Escobars as a way to talk about both elements of soccer at that time.

Michael and Jeff Zimbalist / Portrait by Leslie Hassler

We watch the shoot-out between police and Pablo's armed tanks in which more than 540 police were killed and 1,000 injured. One wonders how so much footage was found and released.

Michael: We hired a great Colombian "fixer" who cajoled hundreds of hours of archival films from 46 Colombian programmers, the police, the press, co-workers, and friends. Tapes were often unmarked. We rented a Medellin apartment and spent weeks going through these and our subjects' family archives. Finally, Jeff and the other editor, Greg O'Toole, sifted through 150 hours of selected footage to pick the shots for the film.

How did you get such detailed and critical information from Pablo's closest cousin and "Popeye," his top executioner?

Jeff: One explanation is that it is therapeutic to go into the story when its been bottled up for a long time. And while anyone can talk about Andres' story, there was no way to talk about Pablo's without hearing from his former companions.

Michael: "Popeye" has been in jail a number of years and feels he's atoned for his sins. He wants to cooperate as far as telling how things were. It's clear that he is excited and reliving those days as he tells his story.

How do you feel your film will help change our image of Colombia as a bed of corruption?

Jeff: We felt a responsibility to give a positive portrayal of Colombia as it is today. We wanted people to know it has come a long way toward legitimately restructuring its athletic programs and its political and social life. It's become a much more secure country with a peace-loving, hard-working population. It's becoming just as Andres wanted.

For more on The Two Escobars: http://30for30.espn.com/film/the-two-escobars.html

To follow Linda Hassler on Twitter: http://twitter.com/lindahassler

To see more of Leslie Hassler's photography: www.lesliehassler.com