For decades, artists like the projectionist Jenny Holzer have found political power in all-caps writing. So why is the Caps Lock key so reviled?

Good Internet citizens are supposed to hate all-caps writing. It's shouty, it's misused. But it can also help solve a modern visual problem. Imagine "someone looking at a feed,” says the Canadian artist Alex McLeod, and wondering, “How can I stand out?”

For a living, McLeod sells phantasmagoric prints and digital files through his website. Twitter is where he hones his online persona, by writing surrealist thoughts in all-caps to attract attention. He's one of an informal group of tweeters who's adopted this style. He's not a grandpa angry about Obama, or a tween obsessed with Ariana Grande. All-caps tweeters are hard to pin down: they can sound infantile or clever, angry or silly. Because they're at the edge of a trend, they tend to seem uniformly millennial (McLeod is 30 years old).

There's a basic utility to the style. McLeod sees Twitter as a crowd he's shouting into, a fantasy shaped by the feed's endless scroll of competing voices. If he communicated as aggressively in person, “my friends would probably hate me,” he admits.

All-caps tweeters twist their humor differently. The modernists and their kin are lo-fi. The Caps Lock Key, as Kanye West once wrote, "IS LOUD.”

Perhaps understandably, writers from marginalized communities seem more inclined to amplify their words this way than others. Last year's slim debut volume of poetry by the Palestinian-Danish teen Yahya Hassan partly got noticed for an obvious reason: every incensed word was printed in caps. Decades earlier, the American poet Langston Hughes legitimized the formula. His entry, a volume of epic all-caps poetry -- Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods For Jazz -- may not have landed as loudly as Hassan's book in its day, but today it is considered one of Hughes' most daring works.

When he wrote it, Hughes was facing the problem McLeod describes, of forcing an audience. His career was in transition. Spooked by the government’s anti-communist stance, he’d begun backtracking on his socialist past, omitting early radical poems from self-edited collections. The former Harlem Renaissance leader was soon getting “castigated for being an Uncle Tom,” says Donna Akiba Harper, a Hughes scholar at Spelman University.

Hughes’ only all-caps work came as a surprise. Written five years before his death at the age of 65, the poem was one of his "most innovative," says Harper, intended to live on as a score for a multimedia performance.

As with Hassan, who wrote as only a teenager can of the sins of his parents' generation, Hughes was in the mood to shout. He began the poem in a hotel room in Rhode Island in the summer of 1960, a day after witnessing a riot at the Newport Jazz Festival. It was the dawn of the civil rights movement, a time of high energy in the black community that led the festival’s headliners, jazz greats like Oscar Peterson and Ray Charles, into prominence.

The rioters were fans, mostly young and white, who found themselves unable to enter the sold-out festival. Their violent attempts to get in anyhow led to the arrival of the National Guard. Today, we might call the riot a show of white privilege. Hughes saw in it a promise deferred nearly a century after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, of racial harmony.

Logistically, book-length shouts are harder to write today. For such a small thing, the Caps Lock key has big enemies. In 2010, Google abolished it from its keyboards in the hope, said the company in a statement, that making all-caps writing inconvenient might “improve the quality of comments on the web.” Three years later, the U.S. Navy followed suit, revamping its internal communications from all-caps partly to appease younger enlists who felt they were being screamed at.

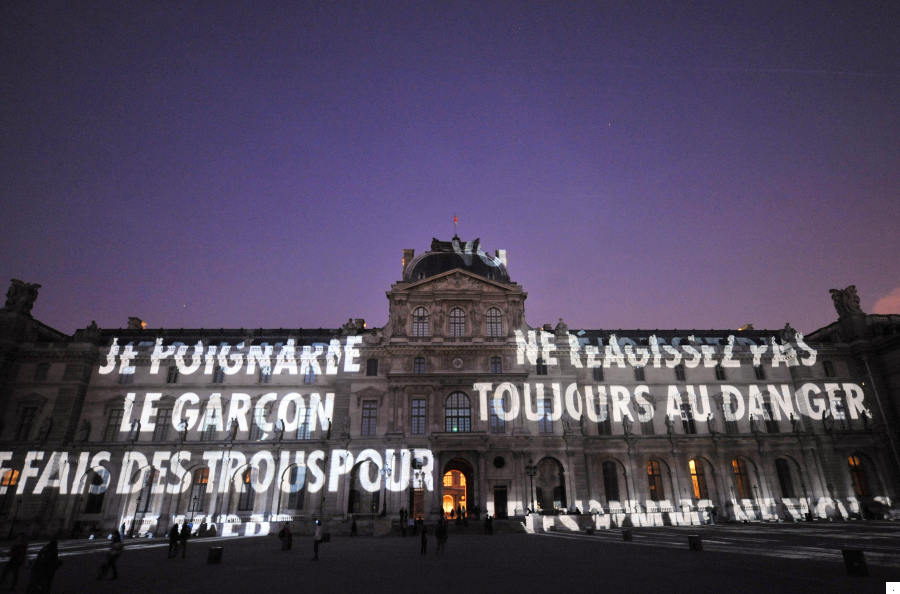

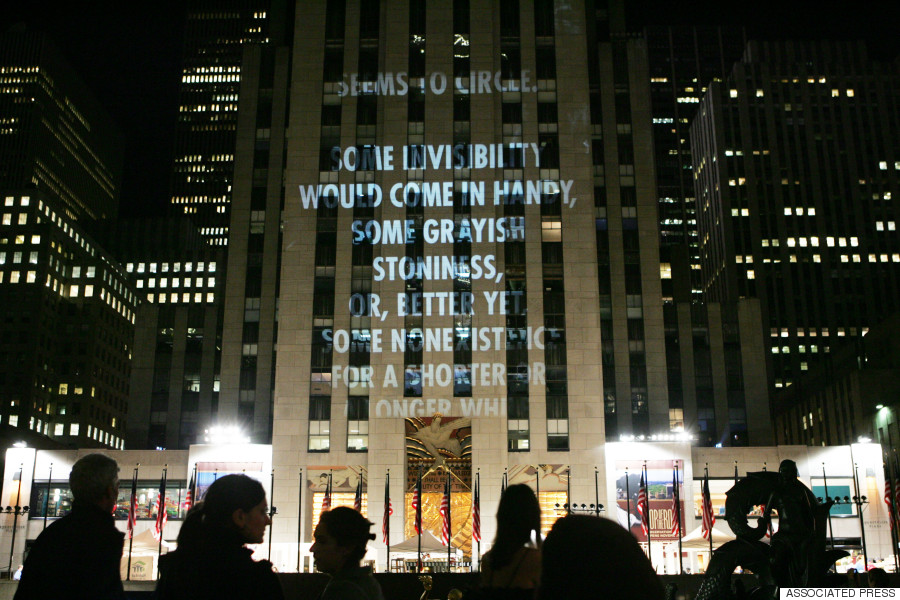

Offline, we celebrate the heft of capital letters. The provocative signage of the artist Jenny Holzer has lit up some of the world's best-known monuments. Protest signs too, are usually written in the largest letters possible. The “twelve moods” of Hughes' title reference a form of individual protest: the traditional African American partner game of “playing the dozens,” a verbal sparring match played until one opponent gives up.

Hughes' all-caps version reveals the hostility under the surface of American life. "ASK YOUR MAMA!" shouts a wealthy black man to his new white neighbor, when asked for a reference for a good maid.

In her 2005 installation For The City, Holzer projected capitalized lines from poems and declassified documents across landmark buildings in New York City in recognition of the events of Sept. 11, 2001.

Those power dynamics shift online. Crazed commenters and paranoiacs complicate the issue so it's the anti-caps crusaders who seem to be the protesters, picketing for peace on the Internet. After the Navy announced its news, the feminist blogger Lindy West articulated a rare counter-argument. Writing (in all-caps, naturally), she defended the "VITAL LITERARY TOOL" of Hughes' toolbox:

I LOVE THE UNFILTERED, UNAPOLOGETIC PUSHINESS OF ALL-CAPS. I LOVE THE BREAK FROM PROPRIETY. I LOVE THE HONESTY OF IT. I LOVE LETTING LOUD FEELINGS BE LOUD. I LOVE HOW ALL-CAPS HELP ME FILTER OUT PEOPLE WHO PRIORITIZE CONVENTION OVER CONTENT, BECAUSE I DO NOT CARE VERY MUCH ABOUT IMPRESSING THOSE PEOPLE.

That line "between convention and content" blurs on Twitter, where emphasis is a binary choice. Either you capitalize or you don't. Italics, bolding and underlining aren’t possible. The scenario isn’t so different from the days of typewriters and early computers, when the Caps Lock key was given pride of place due to similar limitations.

Consequently, all-caps writing has become convention for some users. Jazper Abellera, a 27-year-old all-capser who tweets under the handle @BOYTWEETSWORLDX, identifies less with what he calls "white hipster humor" than with the all-caps absurdity found in the sub-platform known informally as Black Twitter.

Despite the terms, he puts his allegiance down to "a culture more than a race thing." Abellera is Filipino-American; he mostly tweets in and around "hip hop culture," whether that means making fun of Electronic Dance Music, or tweeting a silly, Weird Twitter-apt description of a video he likes. He even sees a through-line in the look of the letters, which remind him of Roman numerals and correspondingly, the luxe vibe of rap videos. (Or another adolescent staple: CD liner notes printed with all-caps lyrics.)

This is Caps Lock as a permanent state, apt for any mood or topic. It's a somewhat avant-garde idea. The Caps key is hardly considered an enabler of nuance. Those who would see it banished cite the inflexibility of the emotion most associated with it, outrage. Even visually, we describe blocks of all-caps writing as insurmountable: a wall of text.

Hughes offers the counterpoint of a shout in different pitches. At one point, he contemplates the flight of Richard Wright, the black writer who followed other black artists to France for a freer life. What in mixed-case might read as a straightforward expression of grief, turns halfway accusatory in all-caps:

AND WHY DID RICHARD WRIGHT/ LIVE ALL THAT WHILE IN PARIS/ INSTEAD OF COMING HOME TO DECENT DIE/ IN HARLEM OR THE SOUTH SIDE OF CHICAGO/ OR THE WOMB OF MISSISSIPPI?/ AND ONE SHOULD LOVE ONE’S COUNTRY/ FOR ONE’S COUNTRY IS YOUR MAMA

Twitter's literary equivalent may not be canonical, but it is wrapped up in identity politics. Most all-caps tweeters cite two men as the originators of the style: the absurdist rapper Horst Simco, aka Riff Raff, or @JODYHiGHROLLER; and @LILINTERNET, an anonymous music video producer. Both are online demigods, the kind of celebrities every 14-year-old -- and almost no 40-year-old -- knows about. Such a creature of the web is @LILINTERNET, for instance, that on the liner notes for Beyoncé's 2014 video album, he is credited for a directorial contribution by his Twitter handle.

In the school-cafeteria-like atmosphere of the Internet, these guys are running entire tables -- bellowing en masse, where Hughes yelled alone. Part of the new appeal of caps writing is how it creates a visual alliance, a code by which outsiders can band together. Take Simco, a white Texan who muscled his way into cult rap star status with multiple aliases and a stylized "rapper" persona. Much of his rise happened online, in message boards, on YouTube and on Twitter. In these unorthodox venues, his signature text style -- all caps, except the letter "i" -- is echoed by fans, like a catchphrase.

Manic earnestness can be powerful PR. As Lindy West wrote (shouted), the all-caps format breaks propriety. Ordinary lines become intimate by virtue of the degree of passion imbued inside, whether written by Riff Raff, Kanye, or @HotMessSWAG, a makeup artist from New Jersey whose offbeat all-caps insights are among McLeod's favorites. These lines may also demand more attention. Studies conducted in the early days of word processors found that our brains treat capitalized text differently than mixed-case, reading each letter on its own rather than in units.

In the digital age, the innovation is practically Hughes-level. "It's like seeing inside someone's brain," McLeod says. "You don’t feel like they’re trying to sell you anything." How often can Twitter make you feel that?