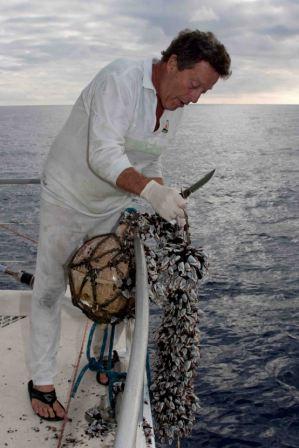

On June 10, 2009 Captain Charles Moore set off on Algalita's Oceanographic Research Vessel for the first leg of a-four month expedition from California to past the Northern Hawaiian Islands to test for plastic marine debris.

Captain Moore discovered the Eastern Pacific Garbage Patch, known as the the Pacific Gyre, and he is continuing his research to help all of us understand that the rapid rise in global plastic production is leading to a rise in plastic pollution and its devastating effects on our oceans and our lives.

Over the next few weeks, I will be posting emails directly from Captain Moore so we can follow his journey and better understand what we are doing to our oceans.

In his email from July 12th, Captain Moore describes how what we know as Styrofoam breaks down faster in the ocean and tells us of yet another danger of the floating plastic trash and its potentially devastating impact on species diversity.

July 12, 2009

Day 31

175 West LongitudeDear Laurie,

Styrofoam is a copyrighted term for a Dow Chemical insulation material. The generic term for the spongy white cups and take out containers we are all familiar with is expanded polystyrene.

Photos of waterborne trash accumulations from urban centers invariably show large quantities of expanded polystyrene containers. When polystyrene -- think clear CD cases that crack -- is expanded, gas is dispersed into the melted polymer creating innumerable channels and bubbles in the material. This makes it a good insulator for hot beverages and food, and gives it a texture that is easy to handle. It also makes it float, since plain polystyrene is heavier than water.

Dr. Anthony Andrady, Algalita Marine Research Foundation's lead polymer scientist, conducted experiments with different types of plastic in the ocean and on land to determine how they lose flexibility, become brittle, and break down into fragments. He found that all plastics except one, expanded polystyrene, broke down faster on land than in the ocean.

For most plastics, heat absorption was the key to rapid embrittlement, and the cooler ocean environment acted as a heat sink, slowing the process. But with expanded polystyrene, the increased access of seawater into the pores of the plastic accelerated breakdown more than the increased heating on land. Dr. Andrady found that expanded polystyrene was the only common plastic to break down faster in the marine environment.

When I sampled the Eastern Garbage Patch, halfway between San Francisco and Hawaii in 1999, I only found about 10% of the particles in our trawls were expanded polystyrene. These most probably originated in debris from Asia following the debris highway created by the Kurashio current's easterly extension.

Now that we are nearly two-thirds of the way to Japan, we would expect to see more expanded polystyrene and to see it in a less degraded state. This is indeed what we are finding, little bits, medium sized pieces and big blocks.

As we approach our goal, the International Dateline, (only 5 meridians to go), we also are seeing more Asian PET drinking water and soda bottles. Since the caps are made of Polypropylene, not PET and degrade faster, when the caps crack, the bottles fill with water and sink, so we don't find as many of them in the Eastern Garbage Patch.

The Asian origin of the debris is corroborated by markings on much of what we are finding. A Taiwanese fishing float stating "Yung Plastic Industry, Republic of China," a Japanese Coca Cola bottle, a thin piece of plastic film with Chinese Characters and a Japanese survey stake.

All of this debris creates an amazing habitat for a great variety of free-floating larvae looking for a place to settle on and grow. According to David Barnes, of the British Antarctic Survey, plastic debris at the surface of the ocean has at least doubled the mass of the organisms living there.

Not only are new species showing up on plastic transported to coastal environments where they have never been before, species that normally live in coastal habitats can be found associated with debris in the deep ocean.

This is analogous to the introduction of European weeds and pests into the New World, species that displaced and decimated the natives. It has been speculated that this mixing of biota could result in a reduction of species diversity in the ocean by half.

From Captain Charles Moore, sailing toward the dateline aboard ORV Alguita.