“You're lying to me," the man said. Carlos Toro took a gulp of wine and tried to maintain his composure. For years, he had dreaded hearing those words.

It was February 2011, and Toro, who was then 61, had come to this upscale steakhouse in Madrid expecting a casual meal between two friends with business to discuss. His companion was a South American diplomat and high-level cocaine trafficker eager to break into the European drug market, where a kilo purchased for less than $1,000 wholesale back home could sell for more than $40,000 on the street. Toro was a onetime top official in the Colombia-based Medellín cartel, which dominated the global cocaine market in the 1970s and '80s.

In his sharply tailored blazer and slacks, a shock of thinning, gray hair atop his head, Toro certainly looked the part of a high-rolling cartel boss. He made up for his short and slightly sagging frame with a confident, easygoing charm. He had offered to facilitate a partnership with a Spanish airline employee who could supposedly transport drugs between South America and Europe aboard commercial planes.

Over the previous two years, Toro and the diplomat had shared many dinners like this one. They had exchanged intimate details about their personal lives, and Toro had even met the man's young son. Everything Toro told him, though, had been a lie.

For well over two decades, Toro had been a confidential informant for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration -- and a very effective one at that. But now the diplomat had stumbled across a piece of incriminating evidence: Toro's airline contact wasn't real. When the diplomat analyzed their email correspondence, he discovered that the messages from Toro and the airline employee originated from the same IP address. If the airline contact really was a Spaniard living in Barcelona, why did he appear to be with Toro in the United States, sending emails from Toro's computer?

"What are you talking about?" Toro replied, trying to sound confused. The man stood up. "Who are you working for?" he snarled. "Are you working for the DEA?"

The restaurant seemed to come to a standstill, and Toro began to panic. Feigning outrage at the accusation, he stormed off to the bathroom and frantically called the U.S. embassy, hoping to reach his DEA handler.

But before Toro could get his supervisor on the line, someone grabbed his jacket collar. Toro turned and swung at his assailant's face. It was the diplomat, and the blow sent him staggering backwards to the floor. Just then, another patron walked in, preventing a brawl. Toro's target picked himself up, and they awkwardly returned to their table.

The diplomat demanded to see Toro's cell phone. Knowing his call log would show his recent attempt to contact the DEA, Toro refused, challenging his companion to turn over his phone instead. When he did, Toro grabbed both phones, slammed them on the tile floor and stomped them to pieces. "I don't trust you. I don't want to work with you. You doubted me. I don't have to do this. I came all the way from the United States to help you," he shouted. "This is outrageous."

Every customer and employee in the establishment was now following the commotion. People stood up, craning their necks to watch the drama unfold. Servers hurried over to defuse the situation. The diplomat, who had no desire for a spectacle, finally left the restaurant.

Toro apologized to the manager, paid the bill, cleaned up the shattered cell phones and headed for the exit. But before he reached the street, he hesitated. What would happen when he walked out the door? Was he about to be gunned down by a drive-by assassin -- or worse, tossed into a car trunk and taken off to be tortured?

Toro took a deep breath. It was after 1 a.m., and the lingering smell of grilled meat was now infused with the acrid odor of cleaning supplies. He pushed through the doors and found the diplomat waiting for him on a metal bench outside.

For a moment, Toro wondered if the diplomat was planning to pull the trigger himself. But his tantrum had apparently been effective. The man seemed almost apologetic, acknowledging that he may have overreacted. Perhaps the airline contact was actually the DEA snitch, he suggested.

Toro bid the diplomat a cold good-night and walked swiftly to his hotel, making sure he wasn't being followed. When he made contact with his DEA handler, he was ordered to extract immediately. Toro got on the first flight out of Madrid. Within a few hours, he had arrived safely in Lisbon.

Soon, he'd be back in the U.S., awaiting his next assignment.

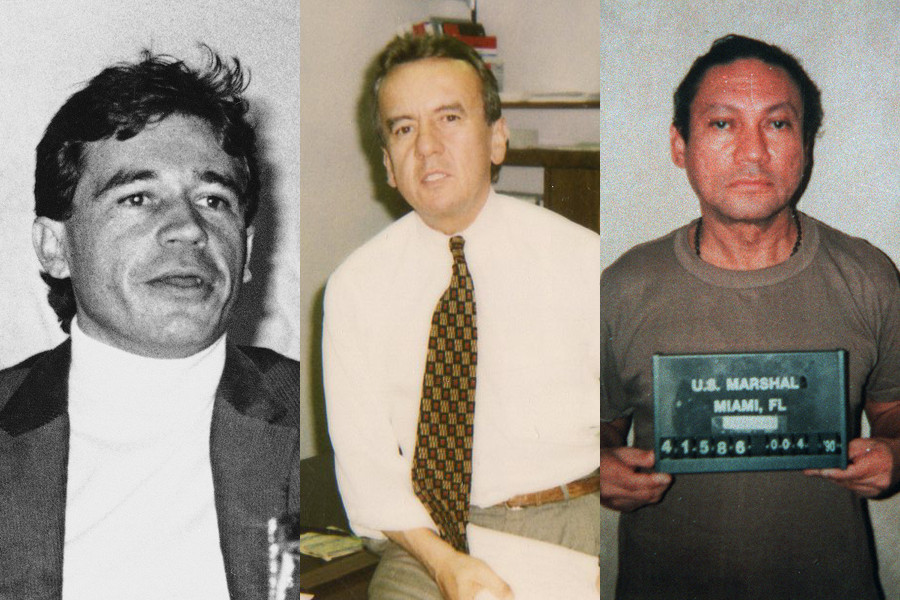

Confidential informants are the lifeblood of the DEA, and Toro is what agents would characterize as a "good asset." He has served the DEA for 27 years. His intelligence-gathering has helped take down arms dealers, money launderers and narcotraffickers across the globe, including legendary figures such as Medellín cartel kingpin Carlos Lehder and Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega. Toro testified against Noriega in federal court. And in 2010, the DEA, citing his contributions to those cases, gave him an award for lifetime achievement. He is one of the most productive DEA assets ever to come forward and tell his story.

Toro's escapades in narcotrafficking often sound fantastical. This is, after all, a man who regularly lies for a living. But Toro spoke to The Huffington Post extensively over the course of several months. He provided numerous documents to support his account, including emails, photos and DEA incident reports detailing the Madrid episode and others. The following story has been based largely on those sources. (The DEA denied repeated requests for comment and typically does not speak publicly about specific informants.)

For Toro, going public in this manner comes with obvious risks. But he feels that he has no other choice. Now 65, he has grown tired of facing down dangerous criminals. He is no longer in good health, too old to square off with would-be assassins or make quick getaways down darkened streets. He wants to retire and live out his remaining years with his family in the United States -- his wife of 35 years, Mariana; their son and daughter; a grandson. (The name of Toro's wife has been changed to protect her identity.)

The DEA, however, has a different idea. For the last five years, the agency has issued Toro a temporary immigration document that requires him to assist in active investigations. If he stops snitching, however, his immigration status will lapse. That could mean deportation to Colombia, Toro's country of birth, where he fears he'd be assassinated by the former cartel associates he once helped put behind bars.

In 2012, Alejandro Bernal Madrigal, a former member of the Medellín cartel, was murdered in Colombia just a month after returning home. He had served time in a U.S. prison for trafficking cocaine, but had bargained down his sentence in exchange for testimony against a top cartel financier. Colombian authorities believe it was a revenge killing.

To avoid a similar fate, Toro has asked the DEA to help him obtain U.S. citizenship or legal permanent residence, allowing him to avoid deportation and access the federal benefits he's paid into over the course of his life. But he said the DEA has refused to change the terms of their arrangement. For years, Toro told himself that this was a partnership of equals. Now, he's come to realize that despite his record of success and years of risking his life, to the DEA he is merely a useful idiot.

Toro's situation conforms to the experience of many other DEA informants, according to criminal justice experts and former agents. There are an estimated 4,000 such operatives working for the agency at any given time, according to a 2005 report by the Department of Justice. "Sources make you or break you," said Finn Selander, a former DEA special agent and a member of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, which opposes the war on drugs. "They are everything for an agent's career."

According to former undercover agent Michael Levine, agents come under enormous pressure to obtain results, and they lean on their sources heavily. "Agents are only interested in one thing, and that is numbers: What can you do for me? Who can you get for me? What kind of headlines can you get? What kind of cases? How far can I go with you?" said Levine, who spent 25 years with the DEA.

When a DEA agent has leverage over an informant, Selander said, "for lack of a more politically correct way of saying it, you've got that person by the balls." He added that agents often view their sources as "dirtbags" and have no qualms about exploiting them.

It's a situation in which the government holds all the cards, said Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Loyola Law School and an expert on informants in the criminal justice system. "If you've committed a crime, then you're on your own," she said. Agents may benefit greatly from a source's information, but there are no legal protections for the informants themselves. In dealings with the federal government, Natapoff said, "those individuals often fare very badly."

Toro was on his cell phone when he opened the door to his Washington, D.C., hotel room on an overcast January afternoon and ushered me in. "DEA," he whispered loudly, pointing to his phone. He placed it on the desk and switched on the speaker, as if to show me there was actually someone on the other end.

When he finished the call, Toro extended his hand, flashing a disarming smile. He had flown in earlier that morning to tell me his life story in person. He was dressed in a blue zip-up sweater and skinny jeans -- an outfit he jokingly referred to as his "drug dealer clothes." Over the next three-and-a-half hours, he paced the slate gray carpet almost maniacally as he painted a detailed portrait of his life. He spoke quickly and assuredly, often without pause -- a regular habit of his. It was easy to see how he had made a career out of getting people to trust him.

Toro was born in 1949 in the city of Armenia, in the heart of the coffee-growing Andes region of Colombia. His family was wealthy. His father had been a pioneer in the broadcasting business, founding one of the nation's first private radio stations.

As a child, Toro recalled, he developed a close relationship with a family friend named Carlos Lehder. They were born just days apart, but shared little in terms of personality. Lehder was a rebellious youth who would go on to become one of the most powerful members of the Medellín cartel. Toro was personable and loyal but always more reserved, a trait he said was a function of his Christian upbringing. As a child, Lehder lived with Toro's family for a few months. In the mid-1960s, however, he left for the United States with his mother.

Toro also traveled to the U.S. in 1967 to attend high school in Hartford, Connecticut, where he could learn English and get an American education. He attended Emerson College in Boston, and during the summers toured with Campus Crusade for Christ and interned for Pat Robertson and the Christian Broadcasting Network. He eventually left school to join CBN and travel the world as a cameraman, before moving to New York in the mid-1970s.

Back in the U.S., Lehder took every opportunity to try to lure his friend away from the straight-and-narrow lifestyle. Toro recalled meeting with Lehder on several occasions, including at two separate parties at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York. In 1978, as America’s cocaine binge was in full swing, he visited Lehder in the hotel's presidential suite.

"He's got 20 prostitutes, there's a kilo of cocaine on the center table, and a bunch of friends and everybody is having a party," Toro said. "We were there for three days, I don't even know."

Lehder explained to Toro his grand vision for a new Colombia, controlled by the cartel and its ever-expanding cocaine empire. Lehder was on top of the world, making $2 million a week and entertaining foreign dignitaries, prime ministers and presidents. He'd even bought an island in the Bahamas, which the cartel would soon be using as a staging ground for cocaine shipments into the States.

Toro visited the Caribbean compound a few times a year in the late '70s and described it as an enclave overflowing with sex and drugs, guarded by a small army of men with Uzi submachine guns and packs of attack dogs. Each time he'd go, Lehder would insist that Toro join the cartel, but Toro remained wary of his friend's criminal enterprises.

In 1980, Toro married Mariana, a Colombian-American born and raised in Miami. Their first child was born in 1981. Shortly thereafter, the family moved from New York to Tamarac, Florida, where Toro managed a janitorial services company. Yet he couldn't deny that he was drawn to the perks of working for the cartel.

One day in 1983, Alvaro Triana, another childhood friend then in charge of the cartel's finances in Florida, showed up with an offer from Lehder. "You will never, never be exposed to the drugs. You'll never touch the drugs. We need you as a PR man. You're the perfect person to do public relations," Toro recalled being told by Triana, a bulbous man with a mop of curly red hair and a fondness for whiskey. "We're having problems finding landing strips to refuel our airplanes, recruiting pilots, training pilots, buying airplanes, repairing airplanes."

The offer would bring Toro a fortune -- and all, he convinced himself, without having to get his hands dirty. Still, Toro didn't want to tell his wife he was getting involved in the cocaine trade that was then terrorizing large swaths of South Florida. Instead, he claimed that they were setting up a scheme to sell contraband luxury French goods, like perfume and lingerie. He said they would have both legal and physical protection, and that they would be moved into a brand-new, villa-style home in Boca Raton and given whatever kind of car they wanted to drive. Toro took a sabbatical from his cleaning business, and within a few weeks, he was working for the cartel.

Over the next few years, Toro's role in the organization expanded. He coordinated logistics for cocaine smuggling operations, arranging flight paths, cutting deals with foreign leaders and paying pilots and couriers. (Years later, he described his responsibilities and the internal workings of the Medellín cartel in a 2000 interview with PBS's "Frontline.")

Throughout the mid-'80s, Toro regularly saw $10 million a week flow through the attic of his home. He also purchased a .38-caliber revolver, which he carried under his jacket.

One day while Toro was out, Mariana unzipped one of the army-green duffel bags lying on the attic floor. It was full of rubber-banded rolls of hundred-dollar bills -- a total of $1.2 million in cash. Mariana had suspected her husband was involved in something more serious than selling stolen Chanel No. 5. When she confronted him, he promised the work was only temporary.

Toro claims the situation left him desensitized to wealth. He was being paid handsomely and everything he could want was at his fingertips, so he never felt the need to save. He had planned to retire after a couple of years but never put money aside, unwisely assuming it would always be available to him.

Respect for the chain of command was a central tenet of the Medellín cartel. So in 1985, when Toro found out that Triana wasn't paying pilots on time, he was faced with a hard decision: go over Triana’s head or risk losing key links in their supply chain. Toro decided to make sure the pilots were paid immediately. He contacted the cartel's financial backers in Colombia, who gave him $7 million to distribute. It was the latest episode in an already escalating feud between Toro and Triana, and perhaps Toro should have known better. Triana was volatile, insecure and impulsive -- not the sort of man you wanted to antagonize.

The next afternoon, Triana showed up at Toro's house looking disheveled and cradling a nearly empty bottle of whiskey. "Come out, you son of a bitch," Toro remembered Triana yelling from his front yard. Triana continued to hurl insults at Toro as they took the argument down the street to Triana's house. In the living room, Triana sank into a recliner and gave Toro an ultimatum: He had 24 hours to leave the Boca Raton house and return the cartel's property.

Toro accused Triana of stealing the money meant for the pilots and threatened to go to the cartel bosses with the allegation. Triana exploded. "I'm gonna kill you!" he screamed, reaching down and pulling an Uzi from beneath his armchair. Toro grabbed his revolver and fired three times, hitting Triana in the chin and the groin and sending him slumping to the floor. The third shot hit the ceiling. "I don't know how I did it," Toro recalled. "I wasn't looking."

Triana was alive and conscious but losing blood fast. The hospital was out of the question: Triana was living in the U.S. under a fake identity. Taking him to the emergency room would have put the entire Florida-based cartel operation in jeopardy. Toro called a former business partner and asked him to send over his son, a medical student. The young man dressed Triana's wounds and gave him a morphine injection, while Toro tracked down a cartel pilot to fly Triana back to Colombia for more extensive treatment. In the middle of the night, Triana was loaded onto a small plane and secreted out of the country.

Toro called Lehder to tell him what had happened, expecting that his old friend would understand. "You shot one of my men?" Toro remembered Lehder saying. "You're dead."

Toro and his family fled back to Tamarac. One morning a few months later, the cartel apparently caught up with him. In a parking lot a few miles from his house, police discovered the body of a young woman, a small-time cocaine dealer Toro had known, in the trunk of a car. She had been stabbed more than 15 times, and her head had been cut off. Toro said he believes she was killed by a cartel hit man and dumped near his house to frame him.

Police arrested Toro for the murder, but with no real evidence to link him to the girl's death, the charges were dismissed. During his 12-hour interrogation, however, Toro let slip that he'd helped the Medellín cartel buy fuel for its planes. That gave the local district attorney a charge that could stick: conspiracy to traffic cocaine. If convicted, Toro would face a 15-year mandatory minimum prison sentence.

Convincing a jury of his innocence seemed like a long shot. Toro had in fact been a party to a massive criminal enterprise. It didn't help that the drug violence sweeping Florida had made many people suspicious of Colombians. An innocent Colombian stood little chance in front of a Florida jury at that time. A guilty one with a taped confession had even less.

Toro's lawyer brokered an alternative: Toro could become an informant for the DEA. If he provided substantial assistance to the agency within 90 days, he could plead no contest to the conspiracy charge and remain a free man, with his criminal record sealed.

If Toro didn't already have a price on his head, he knew that working for the feds would surely earn him one. But 15 years in prison would have meant losing his family, including his two young children. It also didn't hurt that the deal would allow him to exact revenge on his former cartel associates who had turned their backs on him.

Toro's first order of business was to begin identifying cartel assets -- account numbers, stash houses, residences, banks and other properties that had been used to facilitate their drug operation. His handler was Michael McManus, a young, ambitious DEA special agent cutting his teeth in the drug war then raging in Florida. Toro was productive, and when his three months of service were up, he could have walked away from the DEA for good. In hindsight, he should have. Instead, he made a decision that would define the rest of his life.

"Deep inside, I felt that the more I contributed to the DEA, the more the government would appreciate what I do, and I could re-establish my life as a private citizen," Toro said, taking a break from his patrolling of the hotel room to sit on the bed across from me. "I knew I screwed up, and I felt the need to atone and pay back, and to this day I feel that way."

Toro agreed to expand his role with the DEA and became drawn, almost obsessively, to the work. Going undercover provided many of the same things that had led him to join the cartel: an adrenaline rush, a lavish lifestyle, a feeling of importance.

"It's fun to be a drug dealer with a permit -- to be a drug dealer legally," Toro said. "I leave my humble apartment in Miami to go the next day and sleep at the presidential suite in Paris in a Hyatt, and I go and rent a car that costs me $800 a day to drive around Paris, and I have a watch that is a $5,000 Rolex."

Over the next few years, Toro contributed intelligence to investigations that would eventually lead to the arrests and extraditions of Lehder in 1987 and Triana in 1988, as well as a number of other cartel members and their allies in the U.S., the Caribbean and Latin America. As rumors of Toro's involvement in these cases trickled back to Colombia, he became a pariah in his country of birth, and his relatives received death threats. Toro, Mariana and their children spent almost two years in the Witness Protection Program, living in the U.S. under assumed identities, moving from city to city to prevent possible exposure. Tired of the constant upheaval, Toro and his family voluntarily left the program in 1988, against the advice of his supervisors.

When not pursuing cases, Toro took a number of civilian jobs to supplement his wife's income as a medical assistant. Over the years, he scanned mail for the U.S. Postal Service, sold appliances at Sears, handled credit and collections for Microsoft, worked as a repo man for Ford and translated for Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The lure of his DEA gigs -- for which he was paid only minimally -- always superseded his other commitments, however, and his family suffered as a result. "Financial instability defined our lives," Toro's son, now 30, told The Huffington Post.

Mariana said that the DEA knew it had effective control over her husband and didn't hesitate to take advantage of it. "Carlos would find a job and he gets into the rhythm of having regular employment, and then the DEA would entice him with this thing that by his nature he likes," Mariana said. "In my mind he likes that adrenaline, that dual persona -- that persona that lies within him. He doesn't want to be the 9-to-5 and the boring life and the mundane -- he doesn't want that. A lot of times he took the jobs for that reason, because he got bored."

By 2006, the adrenaline rush was starting to wear off. Toro was 56 years old, and he'd spent the past two decades at the beck and call of the DEA. With an eye on retirement, he took a job in Costa Rica as a credit and collections manager with Hewlett Packard. He and Mariana traveled there together. He saw the two-and-a-half year contract as a chance to finally step away from DEA work and ease their money troubles.

Less than a year later, however, Toro flew to Chicago to attend a work conference. As he went through passport control at O'Hare International Airport, security stopped him and took him to a room for a secondary inspection. With the passage of the Patriot Act, any known member of a drug cartel was classified as a terrorist. Toro's criminal record had been unsealed, and he had been declared inadmissible -- never again permitted back into the country.

"The agent told me I had two choices," Toro recalled. "You leave the country today under your own will to the country of origin, to Costa Rica -- you pay for your ticket -- or we have to take you into custody and you'll go through deportation hearings and you'll be shipped to Colombia. I knew I couldn't go to Colombia, because I'd be dead."

Distraught, Toro returned to Costa Rica. When his contract with Hewlett Packard expired in 2009, he was given 30 days to vacate the country. Now he was a man without a home. Toro still couldn't believe he was being locked out of the U.S., a nation he'd lived in and served for so long.

The DEA finally offered him a lifeline, asking him to gather intelligence on a drug-trafficking scheme in South America. Toro dusted off his second identity as a drug trafficker and moved to a new base in Peru.

"I thought, 'If I go back to DEA, this will be solved. I'll be able to come back to the United States very soon,'" Toro said. "It sounded so simple that after working for a few months they would reverse the inadmissibility or that they would make an exception, because it didn't make sense that I wouldn't be admitted to a country that I worked for."

But relief came only when one of Toro's targets summoned him to an important meeting in the U.S., forcing the DEA to devise a solution. In 2010, Toro re-entered the country for the first time in nearly four years with an I-512 form that granted him legal status for a year, contingent upon his continued service to the federal government. (Toro provided a copy of his most recent I-512 forms to The Huffington Post.) He moved back in with his wife, where he could be close to his son and grandson.

Now, the DEA's control over Toro was complete. Every three months, the Department of Homeland Security would conduct an audit to make sure he was still active in an investigation, and the DEA would assess his productivity annually before sponsoring him for another year. If the agency determined he was no longer valuable, his immigration status would be revoked and he could be deported to Colombia.

This type of exploitation is standard practice in the DEA and other law enforcement agencies, according to former agents and criminal justice experts. An informant's immigration status is particularly easy to take advantage of. "The leverage the immigration status gives the government is immense," said Loyola Law’s Natapoff, "so we have seen in recent years more stories coming to light of the government using that leverage in ways that really do hang informants out to dry."

Levine, the former undercover DEA agent, said it's extremely common for informants like Toro to feel that they've been abused by the process, sometimes rightly and sometimes wrongly. But he also suggested that Toro was foolish to assume any amount of hard work and dedication could earn him special treatment. "Once you get caught up in that world, you're on your own. The rule is that there are no rules," he said. "That's a dirty, wormy, rat-eat-rat world."

In March 2014, Toro finally had a wake-up call. Then 64, he was told by an oncologist in Miami that he needed immediate surgery to remove a baseball-sized tumor from his prostate -- a $5,000 procedure. Toro had no savings, no benefits and no health insurance. “I told the DEA, and they said, 'Sorry, we can't help you.' I was dying and they didn't care," Toro said. He claimed that a DEA contact even told him at one point to "stop whining."

Toro turned to McManus, the man who had first brought him to the DEA nearly 30 years earlier. Propelled in part by the successful cases he'd worked with Toro, McManus had moved up the ranks of the agency, eventually becoming chief of operations for Mexico and Central America before retiring in 2004. In one of the highlights of his career, he took down George Jung, the drug trafficker portrayed by Johnny Depp in the 2001 film "Blow." He is now a highly sought-after public speaker and an unofficial spokesman for the DEA.

When Toro reached out to him, McManus lent him the $5,000. McManus denied requests for comment.

Today, Toro lives with his wife in a small one-bedroom apartment. Mariana supports both of them on her modest salary as an administrator at a medical supply company. Without legal status, Toro can't get a job or health insurance. He has no pension and no way to contribute to the rent. When his driver's license expires later this year, he has no way to legally renew it.

"Many people got promoted because of what my husband did," Mariana said. "What did Carlos get out of it? What did my family get out of it?"

In 2010, the U.S. government gave Toro a "lifetime achievement" award and a check for $80,000 -- about $3,000 for each year of work. It was the only significant money he ever made as an informant. But what Toro really wants is a permanent resolution to his immigration problems and an end to his DEA servitude.

With the government's support, Toro could secure a visa or green card. That would allow him to eventually apply for Medicare and retire in the U.S. with the Social Security benefits he has earned over his years as a civilian employee.

In effect, he is asking the DEA to do the right thing. But while Toro claimed he's been treated well by some agents over the years, Natapoff said the overall relationship between the DEA and its informants is not based on fairness. "The whole world of informant use is built on fuzzy ethics, the toleration of hypocrisy, inequitable treatment and often coercion," she said. "So that is a tricky world to ask people to do the right thing."

Toro said the DEA recently warned him against going public with his story and claimed the agency would get him a visa, eventually. But the agency's process could take years, and he would still be required to work as an informant. At his age and with his health continuing to decline, he said he can't continue to wait indefinitely or jet around the globe chasing bad guys. He simply wants out of the devil's bargain he made with the DEA some three decades ago.

"I am not denying that I was at fault by working for the cartel," Toro said. “I feel not that I deserve a medal, not that I should be compensated with money ... but that I should be recognized only as a human being who has made a huge mistake, and that I made it up over and over and over."

Video editing by Christine Conetta.