Three concurrent exhibitions at four galleries in New York representing three generations of women artists mesh the millennial concern for cultural intersectionality with feminist, ecological and global formulas of sustenance. Carolee Schneemann, Further Evidence at PPOW and Galerie Lelong in Chelsea, October 21 - December 3, 2016, revisit the performance art, photo documentation, film projections and video that helped to usher in the first wave of new media feminist art in the early 1960s and remained freshly innovative through the 1980s. At Wave Hill in Riverdale, Of Nature, September 3 - December 3, 2016, a small but concentrated survey of the career of the late Jackie Brookner spans the 1990s-to 2010s by tracing her evolution from studio artist, to installer of site-specific conceptual art, to engaging truly activist eco art among wildlife natural habitats. At Transfer Gallery, in Brooklyn, Morehshin Allahyari's, She Who Sees the Unknown, October 28 -December 3, presents newly fabricated work made with 3D scanners and 3D printers, much of which is rephotographed for video projection in the space. In stating her goal is to "refigure" an ancient, proto-feminist activist art for an emerging generation, she reclaims century-old imagery and objects representing women's nature religion and medicine banned for centuries by Zorastian, Christian and Islamic autocracies, yet which revisited today hint at the hidden side of what would become the province of modern medicine and psychology.

What unifies the three bodies of work are the singular, even oracular focus each of the artists displays in devising a personal physics and metaphysics of culture that unifies the body, mind and world. Whether they favor the ideological, political, cultural, spiritual or theological as their primary path to a unifying world view is relative and thereby less important than the common factor at play -- their approach to building a correspondence of art with the world their art embodies, represents, mimics or points to. The three shows are made even more relevant for arriving at a time when the issue of women's identities, beliefs and politics claim to expand with the notion of a cultural intersectionality that meshes all the variant feminist arts and activisms based on cultural and ideological origins. To bring that intersectionality into the greater history of feminist history and art, we may look to the deep roots, spreading branches and interlacing tendrils of the sciences, metaphysics, poetics and long histories of human life, their languages and iconographies, continually growing to become ever more prominent and understood as composing a holistic vision of the culture-nature continuum.

In this context, the three shows are remarkable for simultaneously reviving the currency of a feminist metaphysics of the body-world continuum that reaches back to ancient millennia. Yet it also informs the scientific quest for a unified model, whereby the quantum, the nuclear, the molecular, the chemical, the biological, the psychological, the terrestrial, the astronomical, the astrophysical are made one unified system modeling the world and our place in it. Until that unified model is arrived at, we refer to vague outlines of the unified theory in terms of the microcosm-macrocosm; the prose of the world; the cyborg fusion of body and object; the correspondence of things; the immanence of intelligent design, if not intelligence in materiality operating at unique frequencies. All these models of the world and more inform both the traditional and new media these three women had independently and in different decades settled on to sustain their political empowerment and personal enhancement as artists.

All three artists also show a marked proclivity for making an art that reflects, at the same time that it is what is reflected, as reality. And that reality is the projection -- truly a much better metaphor than the mirror for an age of electric digitalization of light projected images, and which Schneemann and Allahyari in particular relish to redefine the parameters of an exhibition space. The projection is, of course, a perceptual representation of human perception and affinity. And given that all three artists see the diversity of being as a mesh of difference in coexistence and shared ideas, the projection, mesh, existence and idea all together can be called an 'immanence' of consciousness binding the world within a cultural perspective.

The term immanence was the name given to the theological belief that the entirety of the world is invested with a theistic presence, if not an intelligence, whether it was impersonal, as in pantheism, or presumes the presence of a deity or deistic-like energy immanent in all creation. For our intersectional purposes, were we including the art of men in this survey, we might call the presence presumed in all things to be a 'human immanence', or its derivation, a 'humanence'. In fact, this would be an immanence projected by us into the world, perhaps even an immanence projected by the world onto us.

But since the artworld from the 1970s on has seen this projection of humanence primarily in the art of women, particularly feminists, for our purposes the art discussed here can be said to be a holistic projection of 'feminence'. This is not to be mistaken for the essentialist search for the feminine "in" all nature, but rather a projection into the unity and power of things that women share with men, but derive strength, wisdom and confidence from. The fact that we divide it into 'humanence' and 'feminine', (there is no similar new-world encompassing movement by men searching for a source of power they already culturally presume to possess. And the old order of men just assumed 'humanence' is their designation.) Feminence, then, is merely a condition of the evolution of women through the patriarchal millennia we are emerging from. It is not an energy or source predisposed only to or for women. It is a channeling of the one pervasive and unified projection by women today of their presumed energy and essence as a source of resilience and identity.

At the same time deistic sensibilities aren't excluded in the shared ideology of humanence or feminine -- that is part of guarantee of intersectionalism. Of the three artists here, Allahyari entertains the bygone myths of the essentialist feminine for historical reference, yet one she departs from as essences are what disappear from her work as she newly explains the myths in pedagogical terms. Still, the underlying and fundamental notion of a feminine essence sought by women (and those men interested in "getting in touch with their feminine") within all things emanates as a unifying motivation and ideal propelling such work that can be said to be culturally constructed as a mirror of the mind, as a prose of the world, and as a continuum of microcosm meshes out in constructive expansion to compose macrocosm.

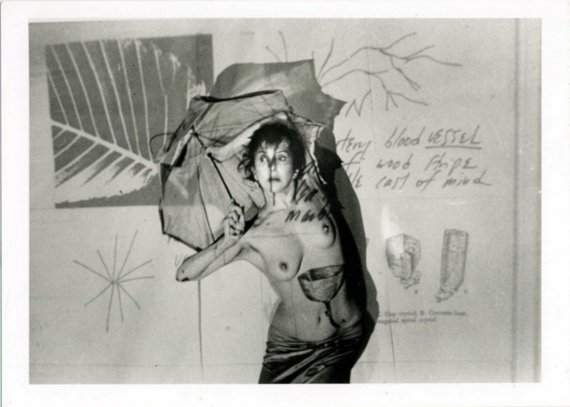

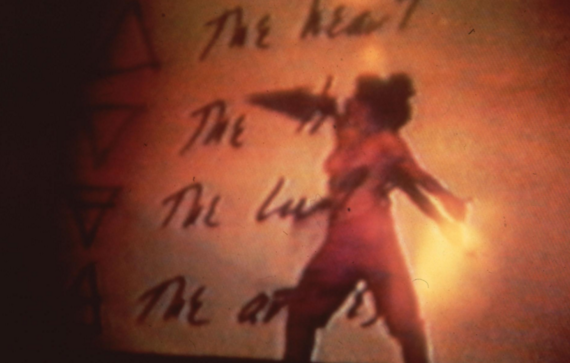

How an artist accesses the all-pervasive immanence is naturally subject to the conditions of her life. Since 1960, Carolee Schneemann used her nude body as a screen that meshed with the theatrical background, and the mixed-media of still and motion picture projections. When Schneemann was seen with the projection of a chalice atop her torso, the connotation is that the body is literally as subjected to receiving all manner of projection of meaningful contents from the mind as the body is capable of being made into a physical receptacle or platform of objects and images. It is in particular Schneemann's reaching for a connective mesh to the world, to a resonance beyond the mundane events of the performance, or the cultural conceits of art to an immanence in all things. It may have been Schneemann, or it may have been Frida Kahlo or Georgia O'Keeffe or Meret Oppenheim or Remedios Varos before her, or Marisol Escbar, Niki de Saint Phalle or Yoko Ono, her contemporaries, all of whom reached for a universal immanence like the old deistic pantheism from which the human form of woman could be said to emanate. As did Kahlo's organic and mineral bloodlines in Henry Ford Hospital, O'Keeffe's flowering vagina analogues, and Oppenheim's fur cup, Schneemann's Meat Joy and Interior Scroll did this literally and physically when her astonished audiences witnessed her dancers rolling around on the floor among the animal meats that were continuities of their bodies, or the artist herself pulling a paper scroll from her vagina to read a manifesto that extended Courbet's, and really all of the ancients', notion that the vagina is the source for the world.

Meat Joy and Interior Scroll are missing from the PPOW and Galerie Lelong surveys -- not that they are needed, so ubiquitous have they become for at least connoisseurs of political art as milestones of innovation. The gallerists are rightfully intent on expanding our acquaintance with the a range of Schneemann's performance art, and other spoken and written monologue art. Much of the imagery in particular is either derived from photo documentations of her performances or remediated imagery and text that originally composed the multimedia slide projections and video screenings that Schneemann wove into her textural and textual fields of space, time and meaning. For this viewer, the textual works in particular resonate with the sound of Schneemann's voice, familiar to anyone who has been acquainted with the soundtracks of her films, videos and slide installations. (Schneemann's voice has a historical resonance in the artworld that is rivaled only by the voice of Yvonne Rainer, whose early, quasi-narrative films, were punctuated by her long and ironic voiceovers.)

Much of the work we view by Schneemann is composed of interplaying resemblances, analogies and punning in the Freudian tradition by facilitating our seeing of vaginas in branching trees; bodies in chalices; erotic stimulants in household pets. Freudian associative thinking, after all, energized second-wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s as did no other figure or ideology, even if it was largely as a catalyst of dissent and delegitimization. The both positive and negative influence Freud, and his defectors Carl Jung and Jacques Lacan, had on the associative chain of feminist empathies with objects, whether as fetishes, archetypes, metaphors or political euphemisms, was mischievously reconstituted by Schneemann into what Donna Haraway would in the 1980s famously call the feminist cyborg that not only makes the inanimate object continuous with her body as a strategy of empowerment in times and places of darkness and fear, but who dissolves the boundary between subject and object by rendering them continuous. Haraway wrote: "The 'eyes' made available in modern technological sciences shatter any idea of passive vision; these prosthetic devices show us that all eyes, including our own organic ones, are active perceptual systems, building in translations and specific ways of seeing." In other words, when we are seeing we are, in Haraway's words, "organizing worlds." (This passage was provided by Jackie Brookner.)

Read more about Schneeman in Denson's essays Breaking the Frame and XX Chromosocial, Women Artists Cross the Homosocial Divide.

As the first self-proclaimed feminist in the Modernist art world (those who came before her, such as the surrealists, Frida Kahlo, Meret Oppenheim, Remedios Varos, and Lee Miller, and before them the Dada artists, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hannah Hoch, were, in retrospect, protofeminists). But given that Schneemann, Brookner and Allahyari are self-proclaimed feminists, the immanence they project through their art can rightly be called a 'feminence'. This includes the invocation by all three women of a history of woman's metaphysical strivings for an almost oracular metaphysics that unites culture and nature through a reading of the body, the mind, and the objects as one expansive text continuous with and signifying the world as we know it.

While art critics prefer to detach the art object, image, performance or concept from the maximalist sensibility of mainstream culture, a cultural critic such as myself prefers just the opposite: to correlate the various mainstream threads and trace them back to their sources. In uniting the concerns of these three artists in a metaphysical feminist immanence we can call a 'feminine', we are visually uniting artists who make images, objects, performances, philosophies and ecosystems posed not as oppositional or dualistic, but rather as seamless and symbiotic textures of difference that propose a holistic antidote to 'the Self' and 'the Other' by uniting them in a systemic mesh of difference and commonality. Maya Deren's 1943 film, Meshes of the Afternoon, comes to mind as yet another vision of a Surrealist feminence. Dream (the structure mimicked by Deren's film), after all, is our living return to the similitude of the all-encompasing Whole. This much is conveyed by the famous montage in which Deren takes five steps around the world, each cutting to a different terrain: cement, earth, grasses, sand, water, and living room carpet.

But before we can begin to use a new word like 'feminence' to discuss the perception of the feminine in all things -- including masculinity, as conveyed by the common symbolism of the X chromosome belonging to both genders, while the Y chromosome belongs only to the male. But before we can expect 'feminence' to be received and utilized by others, we should understand the notions and theories from which such a term is historically derived as well as the crises the word is meant to resolve.

.

Although until now there has been no such term as 'feminence', nor even the more inclusive notion of 'humanence', the term 'human ence' has been esoterically applied in European philosophy, however rarely and idiosyncratically. That shouldn't keep us from conceptualizing a useful and current notion of feminence and humanence to double for the 'immanence" that has historically informed both the ideologies and the actions of religions and philosophies that both united and divided populations for millennia up through the 19th Century. But while there hasn't been much modern art in the 20th Century, and even less in the 21st, to have invested in immanence, the artists of the first quarter of the 20th Century whose radical formalisms had been influenced by Theosophy -- Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevish, Piet Modrian, Paul Klee, and László Moholy-Nagy, among scores of other prominent modernists -- have been vital enough to keep the presumption alive at least as an historical departure point for Modernism, however conflicted that departure has been for its legatees.

The exception has been feminist art. Despite the anti-essentialism of such philosophers from Simone de Beauvoir to Judith Butler, a kind of feminine was invoked by women artists of the 20th Century in reaction to the false rationalism that had long dismissed women's metaphysical alternatives to a patriarchy that has it roots in the notion of a male deistic immanence by law, both in the public and in the home. Feminence, the citation of a feminist presence in all things, is for some a real presence, for others, a rhetorical completion of what has been missing from male-dominated faith and metaphysics alike. Feminence can be seen both in the protofeminist art of Frida Kahlo and Meret Oppenheim and the self-proclaimed nonfeminist art of Georgia O'Keefe. That is because the notion of feminism transcends the political even as it permeates the psychological terrain of cultural and personal inheritance. What Kahlo and O'Keefe intuitively observe in culture and nature (with or without feminism), Carolee Schneemann explicitly interjects into art politics.

Feminism has often enriched its theories and practices with not just metaphors of nature, but a mimicry and reference to the interconnectedness of natural systems: whether it be structural (intersubjectivity, interconnectivity), organic (tendrils, roots, branches), or languages to read (all the world is poetry and prose; signs, signifiers and semaphores), as the ancients read tea leaves, stars, palms, so today we read weather patterns, astronomical configurations, geological strata, molecular structures, DNA strands for clues to a relevant humanence (truth-to-survival narrative) within.

It was Schneemann who spearheaded the expansive metaphysics of women's alterity that until the 19th Century feminists opened nature to women, hid itself away in the wilderness of witches, maenads, amazons, real and mythological, but always made outlaws for their defiance of male domination. If women's religions were more attuned to nature, it is because they were forced to hide deep within its cragged stone recesses and dark forests both literally and figuratively. Schneemann is widely acknowledged for having taken the performative aspect of the abstract expressionists and extrapolated its performanceness with the body. If the Abstract Expressionists were disinclined to acknowledge their female painter colleagues, Schneemann, along with Niki de Saint Phalle in France, was disinclined to accept the male proscription of women's body as generative of art as much as Yves Kline had made women instruments of painting and Willem De Kooning had made them painted objects, despite that thinking, active, conferring women Abstract Expressionists exhibited radically innovative painting and sculpture alongside them.

On a more extensive axis well beyond the political and cultural provinces, Jackie Brookner wrote about and made an art epitomizing the nature-culture continuum and its connectedness with the world at large. On the wall of the Wave Hill gallery entrance, a citation by the late artist (who left us only in 2015) introduces the visitor to the culture-nature continuum informing the drawings, bronzes, biosculpture, photo- and video documentation of her ecological process art promoting and protecting plant and animal species. "The major theme of all my work is that humans are part of larger natural patterns and that we are dependent upon the natural systems that support our lives. My work is intended to foster conscious understanding of this and to instill an emotional connection to nature and a sense of literal Kinship."

Wave Hill's chief curator, Jennifer McGregor, and guest co-curator, Amy Lipton, recount that Brookner strove to break down the barriers between symbol and function, art and utility, interior and exterior spaces for art by making her Soho studio of forty years into a functioning and evolving biosphere, presenting some of its contents in galleries and other public spaces. Tongue Lounge, a large terrasculpture made from earth in the form of a human tongue, doubles as a lounge chair. Although unadorned in the gallery so we can appreciate its natural porous surface, in Brookner's studio it had been integrated into an interior ecosphere along with other such works covered with ferns and mosses, with circulating water trickling down over their rocky surfaces into a pool below. Prima Lingua (below) is the more capacious version, however much the contours of Brookner's sculpture become obscured. The curators chose to exhibit Tongue Lounge in its formal austerity to emphasize its beautifully rudimentary shape and iconographic simplicity. All of which make the sculpture function not only as an organizing centerpiece uniting the work in the space that had been made before and after Brookner's eco-enlightenment, it is also a unifying metaphor for the human continuity with nature in embodying the mind and the body, which Brookner saw as, "a place where taste, sex and speech meet".

Such meetings of pleasures, drives and intelligences catalyze Brookner's drawings and sculptures as porous filters whereby human existence mingles with the material and immaterial existence of all natural things. The finite artistic plenums she depicts and materializes are representative of a holistic and infinite totality of "essences" -- which really are no more than transient human experiences artificially reduced to concepts for as long as they are valuable for practical use. To Brookner the human-material hybrid is familiar yet foreign; they are extensions of experience into the unknown, but receptive, unconscious of the world. The place were the mind goes in sleep and the body in death, where stasis and motion, and with continuity and differentiation, identity and totality, neither in opposition or exclusion.

In such work, Brookner materializes the French philosopher Teilhard de Chardin who saw nature assuming a succession of higher and higher forms of organization, partaking in a hierarchy of increasing complexity from subatomic particles, through atoms, molecules, proteins, cells, organisms, humans, and ultimately to God, or a supreme and omniscient power. Brookner's artistic chain transits from idea to material, to cultural, to universal -- all interpreted as a code of interlocking relations which phases continually between organic and human-altered structures on all levels.

By far Brookner's most successfully integrated work, that crowning the final years of her life's work, are those outdoor, surviving and ongoing activist and ecological process works that bridge human and animal societies living in symbiotic relationships. The Wave Hill videos and photo documents represented several of such works that Brookner installed around the globe. One of those promising to survive her for as long as its community remains committed is that in Salo, Finland. Here Brookner organized local volunteers, regional scientists and students to adapt lagoons that were formerly used in the sewage treatment processes to the needs of migrating birds. The project specifically enables birds to protect their eggs from onshore predators. Having organized volunteers to build three floatation islands, the installations immediately attracted nesting birds with their lightweight "rock formations" doubling in their supply of protection for eggs and as supports for the phytoremediation of indigenous plants that are a food source for the birds and other cohabitable wildlife. Brookner also saw to it that mist emissions from wind-powered aerators installed beneath the islands stimulate microbial life which feed the food chain.

Movng on to Moreshin's Allayari's show, She Who Sees the Unknown, is somewhat of a throwback to 1970s feminism's preoccupation with the Goddess and other female myths from history, these from pre-Islamic central Asian faiths that include what feminists have come to call the monstrous mother narratives. Such narratives are today thought to originally have been catalysts for women's social empowerment spanning hundreds if not thousands of years that, with increasingly patriarchal culture and history, were reformed into misogynist warnings proscribing women's power. Allayari is challenging the archeologists and mythologists who emerged since the 1970s to argue that no such global-historical matriarchy existed beyond isolated regional confines to justify the feminist myth of a matriarchal age preceding the historically confirmed patriarchal societies that formed during the Bronze and Iron Ages in the Middle East. But the provinces of myth and art are not dependent on science to buttress a feminist mythopoetics -- the making of new myths -- or the remaking of old myths to suit new activist social and cultural imperatives.

Allayari revives more than ancient and forgotten myth, however, as she also recalls the narrative accounts and performance tropes that artists of the 1970s, including many feminists, made their trademarks. But the plethora of performance art by visual artists in the 1970s and 1980s grew so cliche and so overindulgent in presenting narrative fictions as indistinguishable from cultural truths, that the genre was made anemic with the same unavoidable redundancies and cheapened formulas that inundate pulp fiction.

But thirty years later, the nostalgic recall of the veteran performance art aficionado combined with the renewed vigor of the narrative voice read aloud in an otherwise hushed gallery space, offers a new generation all the self-conscious, at times overly academic, monotonal pleasures that new beginnings promise. The most attractive being the implicit parallel metanarrative that tells us, "I am not making theater. I am not writing literature. I am making a polymorphic artifact with an activist incentive." It is in that monotone, that academic, that artifact that we also hear Allayari's voice of feminence reverberate. And because she knows she is recounting a nonWestern legend few Westerners know, Allayari's voice resonates authority at the same time that she injects the tension of our historic and ongoing conflicts between and phobias about secular and religious, scientific and superstitious, colonial and rebel, male and female, Western and Middle Eastern, ideologies.

As with all performance art and narrative, particularly those with political overtones, there is the danger that Allayari draws us into ideological portals she has no intention of opening. In a year marked by exceedingly fractious political campaigns in America, the bruising of thinned skins not yet calloused over can present the artist an audience all too eager to fight against the absorption of the feminence she sets free as literally as the setting free of the jinna from a bottle. But Allayari is well aware of this, as is any feminist who publicly unearths the matriarchal myths and histories that are a pathway to cultural immanence. Popular culture since the 1970s has been sending out feminist mythopoetic incarnations modeled on the amazon, the sorceress and the witch with subtle hermeneutics (that is, readings of the hidden prose of the world of nature) that can be read into the world by the uninitiate, as much as read from the world for those intune to humanance and feminance.

The difference with Allayari's generational context that was absent the feminism performance art of the 1970s and 1980s is that she inherits her generation's assumption of a well-debated and applied intersectionalism. In this she talks and writes about moving "beyond a simple binary view of West vs Islam / tech-future vs religious-history." Her methodologies are diversely millennial, which she demonstrates when she projects into the maelstrom the catchphrases of the key geopolitical crisis zones that for her Western audiences sign both the region of her birth an upbringing (she was born in Iran, where she live until 2007) and the proclaimed objectives of her resettlement in the US, some she is in conflict with. "My work undermines the uneven economics of Western technocolonialism and the performative rhetoric of Islamic fundamentalism," she writes, through a ficto-feminist-figural expression of power. I seek to makes visible the invisible power relationships emerging from the age of 'The War On Terror', current fashionable acts of cultural reconstruction, and the ownership/economics of 3D scanned data through a research-based practice and public engagement."

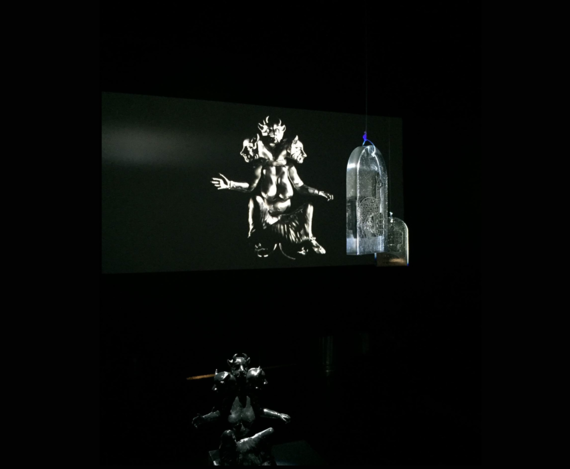

Allyari hasn't yet delivered all that she promises, but the project is still evolving in terms of its narration, objective strategies and especially its reconciliation of enemies. But it is the quieter feminences that succeed, and in large part not because of their rhetorical posturing, but because they are altogether as beguiling as a jinn of fevers ought to be. The installation is composed of a research center with library; a wall-mounted compendium of reproductions of miniature paintings and cards depicting the pre-Islamic myths of Iran and the books that are their sources; a 3D printed black resin sculpture of the jinn, Huma, She Who Sees the Unknown; and two projected videos about Huma with voiceover by Allahyari. In one f the videos, she reads "She Who Sees the Unknown", 2016.

Her name is Huma.

She who is of flame and blaze

She is a Jinn made of smokeless and scorching fire

Among a race created by Allah prior to humans

From the very day of her birth

She was responsible for common fever; '

The fever of fevers' as they called it.

The fever is one of the two most successful of Huma's attributes to be evoked visually in the space, the other being the chain of concurrent visualizations around the space that are analogous to the mesh of the world with all its endowed feminance. Not all the 3D printed artifacts are entirely successful. This isn't to disparage Allahyari's efforts: it's is a limitation of the capacity and materials of 3D printing that may never be worked out, as the industrial processes have not yet been able to match the delicacies in craftsmanship and visual articulation achieved by intensive human labor. The times that the resined surfaces of the figurative sculptures work resoundingly for Allahyari is when they are veiled in shadow so that the highlighting of the black resin gleams as if obsidian. The resin figures also succeed when, in the video, the "lights go on" to reveal the precious jinn idols to be little more than hollow idols, some smashed to pieces. It's a sober reminder that not only do all our myths ultimately become discredited by new generations whose forebears may have been disempowered by the powers behind the idols, but also that many of our own forebears smashed the arts of foreign and bygone populations for appearing to them as sinful idols, in the fashion that the Islamic State (ISIS or Daesh) and the Taliban have been obliterating the artifacts they hold to be by idolaters.

The talismanic images digitally printed on suspended clear resin are much more successfully and theatrically lit to cast shadowy-circular figures on the wall. With the narrative of fever reverberating throughout the space, anyone who can recall the personally momentous captivation of a high fever (for this viewer it was an unforgettable phasing in an out of a 105-degree portal at the age of five) immediately transports back to the blurred and warped images and shapes of the wet heat. It is especially effective because the impression is in high contrast to the archival presentation of the tools of Allahyari's investigation of Huma which cool us after coming back to the present.

If the motifs of immanence, humanence and feminence have any traction in the ideological posturing of our still young century, it is largely because in the 1980s and 1990s the self-proclaimed proponents of (a now phantom) postmodernism made much ado about the end of the grand narratives that propelled, some would say held captive, the history of world philosophy. First principles such as Being, Knowledge, Phenomena, Nuemena (what cannot be known but is essential to what can be known), Nature, Culture -- are no longer the first and central principles from which all other principles and their philosophies issue. We now have embraced not a hierarchy of principles but a mesh of interpenetrating narratives simultaneous and ongoing. As Daniel Bell argued about the so-called ages of 'premodern', 'modern' and 'postmodern' industries -- which were marked by the rise and dominance of the epoch's human industry -- agrarian, industrial, digital -- we have not truly supplanted the agrarian community with the industrial community. Neither have we supplanted the industrial community with the digital. In practice all three remain simultaneous and vital to our survival.

This is how the notion of feminence relates to the notions of immanence and humanance. However we animate the world, and however the world animates us, the process in mutually exclusive, interconnected and constantly at variance in ways that make boundaries artificial at best. The miracle is that artists have from the very beginning implied this. Which is why we can today marvel at a cave painting (now known to be as likely painted by women shamans as by men) with the same degree of awe and astonishment that we marvel at a Frida Kahlo and a Georgia O' Keefe.

**********************

Postscript:

Virgina Woolf was a master of feminence, as ascertained in this excerpt from To the Lighthouse.

"She looked up over her knitting and met the third stroke and it seemed to her like her own eyes meeting her own eyes, searching as she alone could search into her mind and her heart, purifying out of existence that lie, any lie. She praised herself in praising the light, without vanity, for she was stern, she was searching, she was beautiful like that light. It was odd, she thought, how if one was alone, one leant to inanimate things; trees, streams, flowers; felt they expressed one; felt they became one; felt they knew one, in a sense were one; felt an irrational tenderness thus (she looked at that long steady light) as for oneself. There rose, and she looked and looked with her needles suspended, there curled up off the floor of the mind, rose from the lake of one's being, a mist, a bride to meet her lover."

Emily Dickenson was also.

The Soul's Superior instants

Occur to Her--alone--

When friend--and Earth's occasion

Have infinite withdrawn--

Or She--Herself--ascended

To too remote a Height

For lower Recognition

Than Her Omnipotent--

This Mortal Abolition

Is seldom--but as fair

As Apparition--subject

To Autocratic Air--

Enemy's disclosure

To favorites--a few--

Of the Colossal substance

Of Immortality

Listen to G. Roger Denson interviewed by Brainard Carey on Yale University Radio.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on facebook.