In recent years, Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama have used the 1906 Antiquities Act to protect vast marine areas in the Pacific Ocean by declaring them as "national marine monuments." The Act provides a means for a President to establish such protections quickly, without congressional approval. These designations were enthusiastically endorsed by environmental groups and given broad and mostly positive international press coverage.

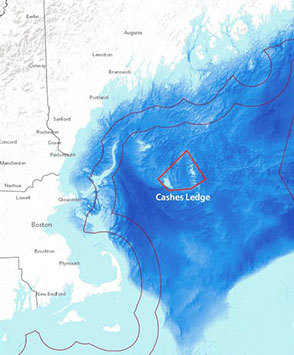

It was logical then for such sites to be identified in the Atlantic Ocean, and two were put forward: Cashes Ledge, an area about 80 miles offshore from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Coral Canyons and Seamounts, a second area some 150 miles offshore from Cape Cod, Massachusetts. A coalition of environmental supporters to include the Conservation Law Foundation, National Geographic Society, Pew Charitable Trusts, and the National Resources Defense Council had lobbied active for the combined designation, preserving an area of 4,647 square nautical miles. Many local businesses, aquaria, educational institutions, more than 500 scientists, further supported the proposal and over 150,000 positive public comments sent to the President and the Council for Environmental Quality in Washington.

Both areas are remarkable. Cashes Ledge is an underwater mountain range and kelp forest, a bio-diverse locus for cold water coral, cod, pollock, dolphins, tuna, squid, and other ground fish, and an essential feeding station for passing North Atlantic right whales, humpback whales, and myriad species of sharks. Coral Canyons and Seamounts supports a comparable natural marine community that is unique to the US Atlantic coast. The argument for designation was not just to regulate fishing in these areas (in Caches Ledge already limited), but also to prohibit all other commercial activities to include oil and gas drilling, sand and gravel mining, and other harmful industrial exploitation of a pristine ecosystem.

Enter politics. Recently, the Obama administration announced that the Caches Ledge proposal was "not under consideration at this time." This decision was announced at a Council for Environmental Quality meeting with fishing industry regulators and representatives who had opposed the proposed designation, concerned that the designation would "permanently" close the area as a final management decision. It seems that the opposition was centered within the New England Fishery Management Council, a group composed of fishermen and state regulators, who expressed satisfaction at the decision. One wonders about the rationale for their objections.

Were they protecting their right to fish eventually in these areas? Were they protecting their right to regulate and administer, against this over-arching intrusion on their authority? Were they interested tangentially in the rights of competitive users? It may be nonetheless that they were asserting the historical principle for the ocean as an open sea for any and all comers to exploit in any and all ways possible no matter the consequence.

The environmental groups saw the Cashes Ledge decision as a postponement and vow to maintain and increase their public campaign. The Coral Canyons and Seamounts proposal for the moment remains in place. Stay tuned.

What does this situation tell us? First, that there is a growing public consensus among scientists, environmental activists, and citizens that conservation strategies, be they marine protected areas or national marine monuments, are necessary for the future sustainability of regional and international fisheries. Second, it tells us that despite much progress among regulators and harvesters about quotas and management agreements, there remains an inherent resistance to policies that further delimit the profitability of individual and industrial fishers. Third, it tells us that there remains a palpable, political, philosophical divide over authority, over jurisdiction and regulation, conflict familiar on land, playing out now at sea. And fourth, it tells us how difficult it is, anywhere, to change how we interact with and benefit from the world ocean.

--

PETER NEILL is founder and director of the World Ocean Observatory, a web-based place of exchange for information and educational services about the health of the world ocean. Online at worldoceanobservatory.org. Peter Neill is author of "The Once and Future Ocean: Notes Toward a New Hydraulic Society" available now.