Recently we marked the 100th anniversary of Louis D. Brandeis' nomination to the US Supreme Court. In a year of discussion on diversity, this moment deserves special notice -- he was the first member of an American minority group to be so chosen.

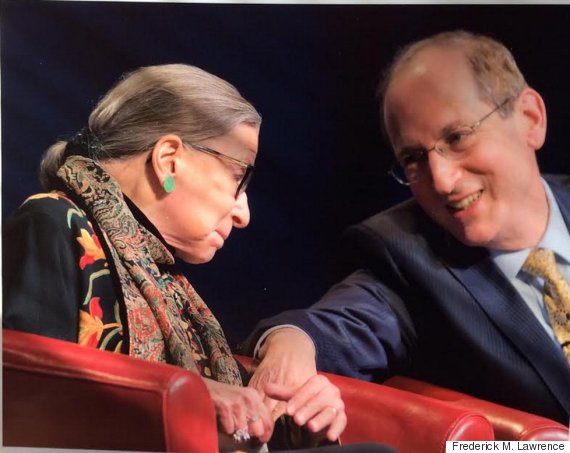

He served his country in spite of vociferous opposition and even hostile fellow justices. Justice James McReynolds famously would leave the justices' conference when Brandeis was speaking and even refused to sign the justices' traditional letter of farewell when Brandeis stepped down in 1939. Most of all, Brandeis commands our attention today because his opinions still matter; they still influence our sitting justices and our law. No better example of this can be found than the words that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg spoke in a tribute I witnessed last week before a crowd of over 2500 students and friends at Brandeis University, where I was proud to serve as President.

As moderator of the event, I was joined by legal commentator Jeffrey Toobin, scholar Philippa Strum, Massachusetts Chief Justice Ralph Gants, and US District Judge Mark Wolf, each of whom addressed the ways in which Brandeis changed the law and the course of American history, as well as his continued relevance today. The real stars of the event were "the Notorious RBG," as Ginsberg biographers Shana Knizhnik and Irin Carmon have lovingly dubbed her in their recent book, and the man we may now call "the notorious LDB."

Justice Ginsburg described in great depth the influence on her own legal and judicial career of the so-called "Brandeis brief" in Muller v. Oregon (1908), the basis of the Supreme Court's historic decision upholding Oregon's law regulating the maximum hours that women could be required to work by their employers. Ginsberg revealed how this work challenged her during her earliest days as a young attorney fighting for women's rights, teaching her to ground her argument in facts, statistics and social history. While she came to realize that in Muller, Brandeis' actual argument ended up limiting women's rights, she followed his example on how to write and how to argue. So many lawyers and justices are limited by their preoccupation with theory and abstraction. For Brandeis and Ginsburg, both brilliant lawyers before becoming influential justices, theory must be grounded in facts.

Brandeis was an exemplar not only of how a lawyer should argue, but how a lawyer should live. He understood the broad spectrum of the lawyer's role, from that of advocate for a client's interest, through that of "lawyer for the situation," through his celebrated role as the "people's lawyer."

Law, for Brandeis, was the key to civil society and social change, and the role of lawyer included his or her obligations to client and society alike. As our panelists discussed, this was deeply personal to Brandeis. He was moved by Matthew Arnold's words: "Life is not a having and a getting, but a beginning and a becoming."

Our panelists of sitting judges, scholars and journalists recognized the challenges that the notorious LDB would face today, especially in light of the challenges to privacy presented by technology and by threats to national security. Brandeis will forever be linked with the legal protection of privacy.

In 1890, he and his law partner, Samuel Warren wrote one of the best-known works in American legal history: "The Right to Privacy." The article in the Harvard Law Review was a tour-de-force, essentially creating a new right but basing it in its deep legal and philosophical roots and in the common law rules of tort law and property law. Brandeis biographer Melvin Urofsky quotes the observation of Harvard Law School Dean Roscoe Pound that the article "did nothing less than add a chapter to our law." Although the limits and scope of the right to privacy remains a subject of intense debate, the existence of the right is widely accepted and generally understood as a fundamental aspect of our legal system.

Brandeis' role as influential writer went beyond his legal scholarship per se. Economic events of the past decade have brought renewed interest in and attention to a series of articles that he wrote for Harper's Weekly beginning in 1913 entitled "Breaking the Money Trust," later published as Other People's Money and How the Bankers Use It in 1914. The ideas and analysis proposed here had a major impact on the discussion of financial regulations and legislation governing the financial industry. They have a compelling resonance today.

Brandeis's written opinions during his 23 years on the Supreme Court covered a wide range of issues. Among the aspects of constitutional law and theory that continue to bear his unmistakable stamp are judicial restraint in the face of legislative decision-making and experimentation, at both the federal and state levels, and the need for constitutional norms to adjust and adapt to evolving standards and contexts, as seen in his classic dissent in Olmstead v. United States (1928), in which the Court held that constitutional protections against unreasonable searches and seizures did not apply to telephone wiretapping. (Significantly, Olmstead was overturned by the Supreme Court almost 40 years later in Katz v. United States.)

Nowhere was Brandeis's judicial brilliance more keenly demonstrated than in the area of freedom of expression. Brandeis is often associated with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in this regard; they were the two great dissenters in a series of opinions in which the Supreme Court upheld restrictions on free speech. Brandeis and Holmes, however, approached the issue of free expression from different perspectives, as illustrated in the first sedition case in which the two justices did not vote together, Gilbert v. State of Minnesota (1920). Gilbert had been convicted of violating a Minnesota statute against interference with or "discouragement" of military service. He had given a speech in 1917 that was highly critical of American involvement in World War I. The Supreme Court affirmed Gilbert's conviction and upheld the constitutionality of the statute, finding that the expression at issue represented a "clear and present danger." Justice Brandeis alone dissented on free expression grounds.

The true power of Brandeis's position comes from his answer to a seemingly technical threshold question: what is the source of any constitutional protections that Gilbert might enjoy? Plainly the First Amendment on its face - "Congress shall make no law ..." -- could not reach action by a state. Brandeis was reluctant to seize on the approach the Court would ultimately adopt - selectively incorporating certain Bill of Rights guarantees into the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. Instead he relied upon the "right to speak freely concerning functions of the Federal Government," which he described as a "privilege and immunity of every citizen of the United States which, even before the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, a State was powerless to curtail."

The right of a citizen to take part, for his own or the country's benefit, in the making of federal laws and in the conduct of the Government necessarily includes the right to speak or write about them; to endeavor to make his own opinion concerning laws existing or contemplated prevail; and to this end to teach the truth as he sees it.

Free expression thus derived its protection, according to Brandeis, from the very structure of the government created by the federal Constitution, a concept later expounded upon by my teacher Professor Charles Black in his celebrated Structure and Relationship in Constitutional Law (1969). This "structural" approach to free expression proposed by Brandeis is striking in two respects. First, it would provide a broad-based protection against state interference with any expression bearing on a national issue. Second, the underpinning of the "structural" approach differs dramatically from the marketplace of ideas notion that underlay the "clear and present danger" approach. The "structural" approach is driven by the need for debate in our political life. Such a comprehensive theory of free expression might avoid some of the pitfalls of the "clear and present danger" approach, which necessarily limits speech based on its expected consequences.

Whereas Holmes saw the ultimate value of free expression as flowing from a "marketplace of ideas" that would produce the best results, Brandeis saw the value of expression as flowing from the very nature of a political and social community. To participate in public debate is not merely to try to reach the best idea but also to participate in civil society altogether. Free expression to Brandeis is at the heart of what it means to constitute a community. As vividly painted by Brandeis: "Like the course of the heavenly bodies, harmony in national life is a resultant of the struggle between contending forces."

For any one of these aspects of the life of Louis Brandeis -- lawyer, scholar, justice -- we would remember him today as a figure of insight, brilliance, creativity, and moral courage. The combination renders him an extraordinary figure in the practice of law, legal scholarship, judicial craftsmanship and jurisprudence, and civic activism on both a national and international scale.