By Tanvir Hossain

Adapted from article originally posted on the BRAC Blog

The name Rana Plaza has become synonymous with Bangladesh. The eight-story commercial building, housing garments factories that manufactured clothes for various fashion houses, came crashing down almost two years ago today. More than 1,100 people died and 2,500 others were rescued from under the rubble. With the extensive coverage on national and international media, one cannot forget the events that followed, and the global backlash ricocheting between the major brands and the Bangladeshi government. Fortunately, it forced them to reconsider many of their unethical practices, including better wages and providing partial compensation for survivors of the collapse.

The fair trade movement has long advocated for certain 'fair' principles, successfully placing a new form of branding on products that carry its label. Often, consumers simply equate fair trade to payment of fair wages. However it goes far beyond a few extra dollars in the pockets of workers to ensure their sustainability.

Today's 'concerned' consumers demand to know that what they are buying is coming from a fair-trade conscious company. This new type of 'social contract' that more and more consumers are entering into is the trade-off in which they can enjoy high-quality goods at affordable prices, while ensuring that the most marginalized producers receive a fair share in the economic prosperity that globalization has brought.

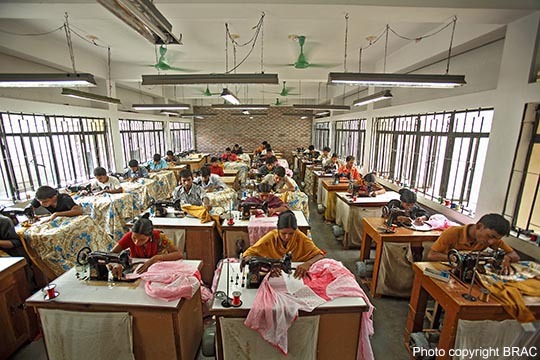

Uniquely, as a BRAC social enterprise, Aarong had built sustainability and fair trade principles into its original business plan over 35 years ago. Unlike in large-scale ready-made garments (RMG) industries, Aarong does not source its clothes and traditional Bangladeshi handicrafts from within a single factory. Instead, it gets its products from a long string of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), forming a supply chain spread across the entire country. This vast network includes thousands of producers, who employ artisans. These groups of artisans bring Aarong's wide range of products to life. The producers receive innovative design input from Aarong's head office, along with instant payment for their goods, marketing and retail support, and other livelihood developmental support.

In return, Aarong seeks that the producer groups maintain good working conditions, fair employment practices for their artisans, and respect for the environment - all principles of fair trade. The real challenge in the model becomes monitoring compliance to these principles; this is where innovation and social auditing is required.

Social auditing is the practice of evaluating a business's ability to fulfill economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities expected of it by its stakeholders. Many social auditing firms have strong tools designed for monitoring RMG factories. International brands are then able to decrease risks in their supply chains by engaging auditing agencies. However, this has left behind the millions of workers in MSMEs that have little to no institutional support to hire auditing firms to monitor their well-being.

Compared to larger factories, MSMEs have a significantly smaller number of workers. But when combined, much like Aarong's supply chain of various producers, there are just as many to account for. As a pioneer in social auditing for MSMEs, Aarong has changed the rules of the game through its own technologically driven monitoring system. Through annual audits conducted on an Android-based application, production units located in the remotest corners of Bangladesh can be provided with support they require to sustain a safe and environmentally-friendly workplace. Being able to centrally analyze their conditions from Aarong's head office with real-time data makes it an efficient way to provide the necessary consultation to these enterprises. There is no one-size-fits-all solution as there may be for RMG factories. In sectors such as handicrafts, which is hardly driven by technology, it can see a revolution when introducing innovative solutions through low-cost mobile applications that can facilitate the process of development. No longer will geographical limitations be the reason for ignorance in businesses and consumers.

"Made in Bangladesh should be a mark of pride, not shame," Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, chairperson of BRAC mentioned in his New York Times op-ed. Through continued synergy and prioritizing social compliance, government, private sector, NGOs, and consumer groups can work to reverse the stigma and prevent such incidents in the future.

Tanvir Hossain is the manager of marketing and sustainability at Aarong.

This page contains materials from The Huffington Post and/or other third party writers. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP ("PwC") has not selected or reviewed such third party content and it does not necessarily reflect the views of PwC. PwC does not endorse and is not affiliated with any such third party. The materials are provided for general information purposes only, should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors, and PwC shall have no liability or responsibility in connection therewith.