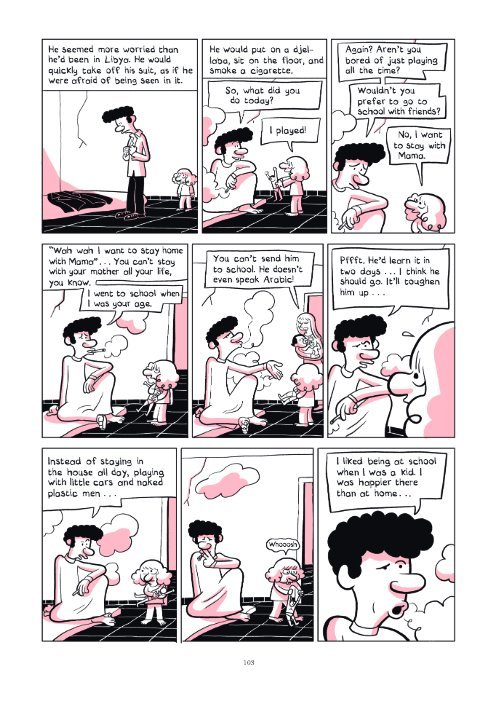

Riad Sattouf is the best known Arab cartoonist in France. He has also succeeded as a film director -- his highly popular movie The French Kissers won a César for best first film. Yet these days the 37-year-old Sattouf's fame is owed mostly to his association with the Arab world -- he is of Franco-Syrian origin -- and his determination to make sense of it through his bestselling graphic memoir "The Arab of the Future" that is published in sequels.

Sattouf's Proustian task is the detailed recollection of a childhood and adolescence divided between two cultures that have been in conflict with each other long before the post-9/11 age of terrorism. No wonder Sattouf grew up not wishing to be part of either. As he put it once, "it's very difficult for me to be proud of being from Syrian origin, of French origin. So I don't know. I think everybody should be equal, you know? I feel myself much more like a comic book author -- it's my first nationality."

Sattouf is not an opportunist: his graphic autobiographical testimonies had begun long before the Charlie Hebdo carnage last January (Sattouf was for a decade the only cartoonist of Arab heritage at Charlie) and "The Arab of the Future" in particular came about after the 2011 uprisings in Syria and Sattouf's own battles with the French administration to help his Syrian family come to France. But his timing was wicked. The escalating tension between his two inherent cultures has become Sattouf's greatest challenge and advantage: more readers are following him now than ever and "The Arab of the Future," like "Persepolis" nearly 10 years ago, has helped revive a genre whose greatest asset is humor.

Ironically, humor was never part of extremist Islam; on the contrary, it is humor that has triggered some of its most violent attacks. From Salman Rushdie to cartoonists in Denmark and, of course, Paris, artists and intellectuals of all religions and convictions have been targeted, hurt and killed by Islamic extremists simply because they made jokes about Islam. Sattouf, who just became a father last year, does not like to disclose if he ever receives hate mail or threats (my question on the matter remained unanswered). Certainly his determination to complete the four volumes of "The Arab of the Future" (he is currently working on the third), indicates that it doesn't matter.

In the following conversation Sattouf spoke to me about the legacy of his divisive identity, his decision to expose his father's pan-Arab extremism, the particularities of the Muslim world and why he left Charlie Hebdo a few months before the attack.

Michael Skafidas: In light of the recent ISIS attacks in Paris, your best selling graphic memoir "The Arab of the Future" acquires a new dynamic. Even though it is narrated through the point of view of you as a child, it can still be read as a politicized quest for identity of a European Arab who tries to make sense of the present by digging into the past. You have repeatedly expressed your wish to remain "apolitical." Is that still possible?

Riad Sattouf: I know it is impossible to be apolitical, every narrative is political by nature. "The Arab of the Future" is obviously political, in that it proposes a naive point of view on often terrible situations and lets the reader judge them. As a reader, I do not really like artworks that tell me what to think too obviously. In my book I tell the story of my family, a family of two different cultures: my Syrian father and my French mother, and me, the result of this mixture. It was also the mixture of two worlds with very different economic levels. I saw extremely violent situations in my village in Syria, people living in big trouble, yet determined to be the happiest in the world. I think that it's always interesting, to put it all in perspective. I present things through the lens of privacy. I let the reader to judge and form his own idea.

I saw extremely violent situations in my village in Syria, people living in big trouble, yet determined to be the happiest in the world.

MS: It's been said that your memoir is like Proust in graphic form. But unlike Proust, "The Arab of the Future" does not express particular nostalgia about your nomadic childhood. Your wanderings as a child in your father's homeland, Syria, and Libya are recollected as a rather traumatic experience. Or would you say that behind the negative -- some critics mentioned the word "orientalist" -- depiction of the Middle East there is indeed some nostalgia about your childhood there?

RS: My book is about sensual sensations, about an intimate point of view of how it was to live in those countries in the '80s as a child. It's a child's point of view. And I think the critics are making a mistake using the term "orientalism" to describe my work. Orientalisme in French is an "idealized vision" of the oriental world. My work is not an idealized vision! But I guess a lot of occidental "Arab world observers," as well as "Middle East" specialists are still bound to the "orientalist" vision; they accepted for many years the dictatorships of those countries as normal regimes. I consider all humans to be equal; I consider that all humans deserve the same rights to education, access to all books written by other cultures, and freedom of choice, whether they are from Syria, Greenland, Japan, or the U.S.

A lot of occidental 'Arab world observers,' as well as 'Middle East' specialists are still bound to the 'orientalist' vision; they accepted for many years the dictatorships of those countries as normal regimes.

MS: Your book describes the radical cultural shifts between France and the Middle East from the point of view of a child who didn't fit in either place. "Kids in France seemed dim to me," you have said. "They were overprotected, excluded from confronting reality. The children in Syria and Libya were left to their own devices and were far more autonomous. There was a great difference in maturity." Where does your own maturity stem from, the French or the Arabic consciousness?

RS: For people who have grown up in a rich occidental country it remains difficult to realize and accept that the way of life that I have known in the town of Ter Maaleh [Sattouf's father's ancestral village] in Syria, near Homs, and I relate in my book, was indeed very close to the experience of France in the early 20th century.

There are several historical and literary accounts illustrating the harsh reality of life in a Western country like France back then. Prosper Mérimée told stories and depicted harsh scenes of rural life in the rural Corsica of the 19th century that often remind me of my village in Syria. This is also the case for Marcel Pagnol. I also read Mark Twain recently and I found many common points about the harshness of country life and the reality of living close to animals.

In The 400 Blows, François Truffaut portrayed his school in France in the '50s and his description was very close to what I experienced in Syria. For example, as I describe in my book, there was an old woman who lived near my French grandmother, in the west of France; she got by without electricity and running water; she wore clogs and never went away from her fireplace that continuously burned. She lived in extremely precarious conditions, worse than what the people in the village in Syria had known. And yet it was in France. The little children of my Syrian village that I describe in the book were set free very early; they were very independent, as opposed to the little French kids that at a similar age were very protected. So, that's what I saw. As for me, I cannot say. All I can say is that I think I was a little cowardly and that my Syrian cousins have hardened me a little. . .

MS: You are the offspring of opposite worlds, a French Catholic mother and a Syrian Sunni Muslim father. In your narrative your mother's voice represents reason and skepticism, while your father comes across as an utopian pan-Arabist, a loquacious fan of Qaddafi and Assad and occasionally a would-be anti-Semitic dictator who, near the end of Volume 1, tells your mother that "one day, I'll stage a coup d'état and I'll have everyone killed." Your father is gone now, but, still, it takes some guts to expose publicly one's father's ideological inadequacies and follies. Would you have ever published your memoir if your father was still alive?

RS: I've never really asked myself these questions. I started recording my autobiographical experiences from Syria in France more than 13 years ago in my first book called "My Circumcision." Obviously, it takes time to digest certain things and to be able to tell them. In "The Arab of the Future" I describe the fascination of a small child with his beloved father who, as it happens, belonged to the extreme authoritarian wing of pan-Arabist politics. This is something that can make a reader very uncomfortable. How can you love someone who wants to execute people? How long does it take to realize the absurdity of the situation? This conflict between the naïveté of childhood and the brutality of the adult world interests me enormously because it echoes the relationship between the people and their leaders. Why do we refuse to see things as they are? Why do we need leaders to think for us and show us the way?

How can you love someone who wants to execute people?

MS: You used to draw for the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, but you left last year, prior to the shooting terror attack this past January that left 12 dead. What was the reason you left the magazine after 11 years?

RS: I had a particular position at Charlie Hebdo. I was not a part of the editorial staff. I was not making political drawings or satirical cartoons. I was drawing a comic page inspired by reality that was called "The Secret Lives of Young People." That graphic column told of scenes I had seen on the street and featured young people. I never went to the editorial offices, and I always sent my cartoon by email. I stopped this series because I was depressed by the harshness of what I was seeing on the street and had to tell every week.

Around that time a French newspaper, Le Nouvel Observateur, offered me an opportunity to do a weekly comics page and so I left Charlie Hebdo. I decided to change completely and I proposed to Le Nouvel Observateur the idea of "Esther's notebooks," a comic that I base on the life of a 10-year-old a girl, the daughter of my friends. She tells me about her life, her friends, her vision of reality and I draw the pages. I let her speak. I will hopefully follow her to the age of 18. I want to observe my comic character growing.

I stopped this series because I was depressed by the harshness of what I was seeing on the street and had to tell every week.

MS: Cartoon and comics were an inseparable part of 20th century popular art; they enthralled adults and toddlers alike throughout the Western world -- I understand that Tintin was one of your early influences. But after the 1990s or so, their popularity declined until Satrapi's "Persepolis" turned out to be such a success in the last decade. Now your books contribute further to the revival of the genre. Interestingly the comeback of the genre has been staged by graphic novelists who expose their Middle Eastern cultures of origin or descent. Is that a coincidence?

We insist seeing the Muslim world as a whole, but there are a thousand ways of living there.

RS: I do not know. People are realizing that the Middle East is not a big mysterious region where everyone is the same. If Marjane Satrapi had been brought up in Norway and recounted her childhood there, and if I had been brought up in southern Italy and described it later, nobody would have said that our experience tells of a general experience of "the European world." Countries and people are different from one place to another. We insist seeing the Muslim world as a whole, but there are a thousand ways of living there. Persia is a very different place than the "Arab world," and the Arab world doesn't mean anything either, because life is very different between let's say Tunisia and Saudi Arabia. I hope there will be lots of testimonies from Arab countries. People need to talk about themselves and their lives. The comic expression, which is again popular and part of the new media, is dynamic and the best medium for this.

The first two volumes of "The Arab of the Future" were released in France in 2014 and 2015. The English edition of Volume 1 was just published in the U.S. by Metropolitan Books.

Earlier on WorldPost: