It took less than a day after the massacre of staffers, policemen, a visitor and a security guard at the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris for the discussion in India to swing back towards the need for "responsibility."

Kiran Bedi, former senior police officer, now a prominent politician, tweeted just hours after the attack by masked gunmen that killed Charb, the editor at Charlie Hebdo, and many of his staff: "France Terror-Shoot-Out sends a message: why deliberately provoke or poke? Be respectful and civil. Don't hurt people's sensitivities!"

Even by the thick-skinned standards of contemporary Indian discourse, Bedi's tweet was remarkably insensitive. But it was also undeniably representative of the way the Indian discussion on freedoms of expression has developed -- or been choked off, depending on your perspective. That question, "why provoke?", needs to be more closely examined, because it has strangled so much of Indian intellectual and cultural activity -- and everyday life -- for far too long.

In 2006, when the Danish cartoon controversy came to a head, many writers in India felt stampeded into one kind of response or another. To support the stance Charlie Hebdo took, republishing cartoons that carried images of the Prophet Muhammad that many Muslims found offensive, was to support the principle of free speech unhindered by the threats made by the religious.

But there was little space for those who wanted to say that they found the cartoons gratuitously offensive, did not endorse them personally, but felt that those who had drawn them and published them should not be persecuted or harmed in any case. I began following Charlie Hebdo's work then, especially its provocative covers, which took on the Pope, Jesus, Jews, rabbis, French leaders, the Prophet Muhammad, the Boko Haram victims, Islam, Christianity, Judaism etc. I found its work childish and sometimes offensive, but I admired the magazine's determination to offend all parties equally.

As I learned about the cases it had fought in the courts, my view of the Charlie Hebdo editorial team shifted: the cartoons might have been juvenile, but the team's belief that free expression must accommodate all forms of satire, protest and parody was deeply serious, and embedded in a tradition of speaking rude, outrageous truth to power that went back centuries in France. Charlie Hebdo's flaws, to me, were glaring and remainded worth analyzing: it had mocked Christianity and France's politicians with a comfortable familiarity, but its mockery of Islam, African politics and even in one cartoon, India, were filled with stereotypes. As the writer Kamila Shamsie said on Twitter: "There are conversations to be had about the distinction between 'offensive' and 'racist'. But the fanatics make it harder to have them."

"I had thought of Charlie Hebdo with some envy. . . They had, I thought, been able to exercise a freedom that many Indians had not been able to claim."

It might be hard to believe today, but in the eight years or so that preceded the day when gunmen went into its office, calling, "Where's Charb? Where's Charb?" before indiscriminately killing the editor and several staffers, I had thought of Charlie Hebdo with some envy. The staffers had gone to court and won their cases; two of France's premiers had backed them on the right to continue being offensive in the same decade when we in India had lost the right to offend. They had been able to exercise a freedom that many Indians had not been able to claim.

Despite the threats made by Islamic groups against them, Charlie Hebdo had continued to publish, with the support of its community, its courts and even for the most part, its state. I thought it had found a way to work in relative safety, that it had escaped the always-present threats of violence that had silenced and diminished so many Indian artists, writers, filmmakers, liberals, journalists, rationalists, atheists, academics, scholars and publishers, muting some, turning some into exiles or pariahs, mutating many others into cowards. I thought that Charlie Hebdo's staff had freedoms we could only imagine, but that was before the carnage in Paris.

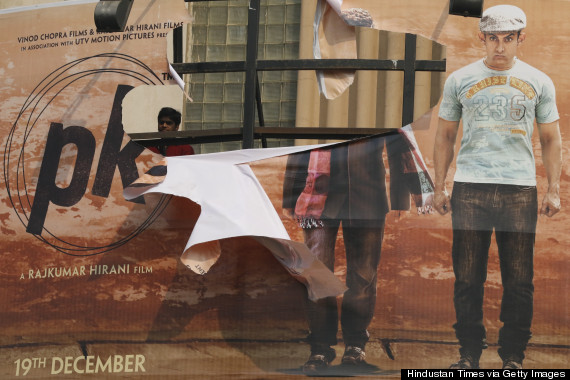

(Poster of Aamir Khan in Bollywood film PK torn by activists of right wing organizations who accused Khan of hurting religious sentiments of the majority community and demanded a ban on the film)

(Poster of Aamir Khan in Bollywood film PK torn by activists of right wing organizations who accused Khan of hurting religious sentiments of the majority community and demanded a ban on the film)

The Trap of Decency

Why provoke when the price is so high, when the innocent could be and are caught in the crossfire? Why not just stick with art or opinions that are inoffensive? These questions have come up again and again in the Indian context, and elsewhere in the world. Charlie Hebdo's cartoons raise a related question: do creators, artists, writers, opinion-makers need to be more responsible or more sensitive given the inflammable nature of the times, the legions of those looking for an excuse to perpetrate acts of violence?

In India, many are caught in one of two traps when they try to respond to the body of work produced by Charlie Hebdo.

The first is the trap of decency, even more powerful in a country where free expression is treated as a luxury good, to be bestowed as a treat when circumstances are favorable.

For far too many people, support for an artist or content creator is conflated with endorsement, and it is genuinely hard to understand why you might defend the right of someone to create work that you might dislike, be bored by, think in bad taste, or even consider offensive.

Decency demands -- or used to, in a crowded and once-secular society -- that we try not to offend others, that we adjust out of politeness. The idea that you might defend an essay by A.K. Ramanujan, a book by Salman Rushdie, a series of paintings by M.F. Husain, a film by Deepa Mehta or Aamir Khan, or an attempt by rationalist Sanal Edamaruku to debunk "miracles" on principle without necessarily agreeing with or liking their work is still an alien one. Free speech debates often veer into a discussion on content -- why should x have chosen this subject, why should y have written in this particular way when they had other choices -- and this tendency is particularly pronounced when people are personally uncomfortable with or offended by the content in question.

The second is the trap of fear, which leads to a belief in the value of appeasement.

The fear is usually the fear of violence that might be unleashed in an irrational, unpredictable manner by either committed groups of religious fundamentalists, as in Paris, or by political goons, as has been increasingly common in today's India. It is this fear that makes many blame the victims of violent attacks, from the team at Charlie Hebdo and the two police officers murdered alongside, to artists and writers like Rushdie or the late Husain, for the violence visited upon them. Some blame the victims openly, suggesting that they had it coming and that they should have known better than to choose incendiary subjects.

Some use more subtle methods, suggesting that artists, too, have a responsibility to act with sensitivity, to rein their worst impulses in, to refrain from offending. Often, the real fear is that the artist or writer or journalist will bring threats, or escalating discomfort, or terrifying violence, rolling in the direction of others, will threaten the uneasy balance that still allows for a semblance of normalcy in India. Without this fine balance, the country might have to discard what is left -- the holding of exhibitions and literary festivals, the publishing of books and magazines, the year-round university seminars and lectures.

In this scenario, publishers who pull back books, as Penguin India did so disgracefully with Wendy Doniger's "The Hindus," or agree to subject their books to a further process of review, as Orient Blackswan and Aleph have controversially done, are condemned only by a small section of liberals for caving in. Many others, including many writers, journalists and opinion-makers, see the compromises made as a pragmatic reaction to the pressures of the times. Many have argued that freedom of speech must be limited in India, that the creative and academic community must be prepared to sacrifice some rights for the sake of preserving the peace.

The problem with following a policy of appeasement is not just that this is ideologically dangerous, as the respected Indian historian and professor Romila Thapar pointed out in a blunt speech in late 2014:

"It is not that we are bereft of people who think autonomously and can ask relevant questions. But frequently where there should be voices, there is silence. Are we all being co-opted too easily by the comforts of conforming? Are we fearful of the retribution that questioning may and often does bring?"

Why was there so little reaction among academics and professionals, Prof. Thapar wanted to know, to the banning and pulping of books, the changing of educational syllabuses, the questioning of the actions of several organizations that act in the name of religion, if not in conformity with religious values? Appeasement becomes a habit, and then so does silence, and the avoidance of difficult questions. The anger that could not be safely expressed by many for fear of reprisal, against, say, either Rushdie's Islamic fundamentalist persecutors, or M.F. Husain's Hindu right wing detractors, turns in another direction. In India, that anger is often directed at the victims -- why did they have to provoke, did they not know what response they would get, and crucially, do they not see the trouble they might get everyone else into?

"It is easier to believe that a massacre was the victim's fault, than to accept that one's own comfort and safety depend almost entirely on not attracting the attention of fundamentalists, terrorists, thugs or the private armies controlled by corrupt and violent politicians."

This is how the artist M.F. Husain was exiled, the author U.R. Ananthamurthy hounded before his death last year, and Rushdie made to feel increasingly unwelcome in his own country. Dislike is useful; it allows people to step away from both their fear and their dismay at being unable to protect the books, art, conversations, and free spaces that they were once able to claim. And yet none of these gestures of appeasement have been effective in stemming the rise of hate speech across religious or political groups in India -- in fact, the relative suppression of more moderate voices has in effect handed over the loudspeakers and the mikes to the bullies and the bigots.

(Indian born British writer Salman Rushdie)

(Indian born British writer Salman Rushdie)

The Price of Not Offending

It is only when you stop sifting through the content, looking for possible flaws of taste or insensitivity, and stop interrogating the creative community over the purity of their intentions that you can move to more useful ground: the question of principle. The right to offend was only one part of the principles that the team at Charlie Hebdo lived (and died) by; the other part was the principle that has most sharply divided humanity in this century, ie, the idea that all of us have an absolute right to question religion. This is where the argument that Charlie Hebdo could have somehow avoided the terror attacks by being a little less offensive or a little more sensitive falls apart. In August 2014, Bangladeshi TV host Nurul Islam Faruqi, was visited by five men at his home in Dhaka; they tied up his family and slit his throat. Faruqi used to host religious programs, and was an imam himself. His crime was not that he used offensive or insensitive speech -- he was murdered for speaking out against superstition and for his criticism of Islamic fundamentalism. A year before Faruqi's murder, the rationalist Narendra Dabholkar had been killed in August 2013 in India, by two unidentified gunmen. Dabholkar was not someone whose speech was either incendiary or deliberately offensive. But his work on bringing in anti-superstition laws had been strongly opposed by some members of the BJP and the far-right regional party, the Shiv Sena, which claimed that an anti-superstition/ black magic law would adversely affect Hindu culture. Nor was Sanal Edamaruku, president of the Indian Rationalist Association, being disrespectful or offensive when he did his many exposes of "holy men" and their fake miracles. And yet in 2012, when he exposed the phenomenon of holy water apparently dripping from the toe of a statue of Christ as a consequence of bad plumbing, he faced a barrage of hate speech cases and escalating threats. Edamaruku now lives in Finland, not by choice, but out of necessity -- it is not safe for him to come back home. Responsibility cuts both ways. It is true that you cannot reason with a fundamentalist, of any religion, that there is no rational argument to be had with armed men bent on murder. But civil society and religious organizations have their responsibilities, too, and one of them is to enable and support those who want the freedom to question, to create, to debunk, and yes, even to mock. It must be kept in mind that what the team at Charlie Hebdo died for was not just the right to offend, but also the right to challenge and question everything -- including religion, including Islam. The promise of free speech goes far beyond the schoolboy thrill of being able to offend; the real promise of free speech is that we all hope to live uncensored lives, free to create in peace, and free to ask questions of or satirize the leaders, and the institutions, that run our everyday lives.

Why provoke, why defend those who are deliberately provocative? Because the bullies and the men with guns are at one extreme, and the Charlie Hebdos of this world -- offensive, irreverent, deliberately pushing the boundaries of satire -- are at the other. It is not necessary to follow in Charlie Hebdo's footsteps in order to respect, or mourn the team. But if we want to live lives that are not muffled, censored and fearful, we must learn to give those who do provoke our support. If we don't, the trammelled freedoms we have left will shrink even further.