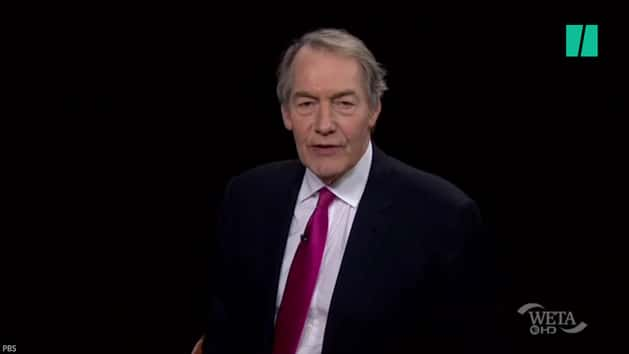

A few years ago I belonged to the group of people who thought that working for Charlie Rose represented the holy grail of journalism. There are few jobs that allow you to travel to Damascus to interview Syrian President Bashar Assad, or to the Kremlin to sit down with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Plus, some of the young women I looked up to most had worked for Rose.

But I wasn’t aware of the toxic culture bred by Rose until I experienced it firsthand. As first detailed in a bombshell Washington Post report published Monday, he had a habit of seeking out and preying upon young women like me ― women who were earnest and vulnerable but also ambitious and willing to try to look the other way about certain matters if presented with the chance to work for one of the greats.

We were lucky just to be considered for such an opportunity, as Rose repeatedly reminded me when I interviewed with him for a potential job. (I reached out to Rose to see if he remembered our encounter. He did not reply.)

The Post’s story details varying degrees of sexually predatory behavior, but the parts that most resemble my experience are the casual preludes, the informal drinks and off-site, off-hours meals, the abusive rhetoric that makes women question their place in journalism. The article is a reminder of what I came to terms with after my final encounter with Rose: His behavior doesn’t so much cross lines with young women; it fudges them to the point that there’s nothing left to cross.

In June 2014, I had an acquaintance who worked as Rose’s assistant. She met me for coffee to talk about the position. As it turned out, she planned to quit soon and would need to find someone to replace her. But from the get-go, she was pretty frank about the not-so-glamorous aspects of her job.

She told me Rose had developed a pattern of pretty much only hiring attractive young women who went to Ivy League universities and that he treated his producers like family because he had no children of his own. After-hours drinks and meals with him were normal ― and expected, she said. She also told me Rose had a pattern of berating his employees and was prone to having a feisty temper and mood swings, but that he was also known for heaping adoration on staff members.

I didn’t heed these warnings.

“Friends and family members raised the obvious red flags, implying that it was strange to meet over drinks. But most couched their concern by reminding me how cool it was to be presented with such an opportunity.”

She arranged a meeting, and told me to show up at the Bloomberg offices at 6:15 p.m. one weekday. She said that we would either have a meeting at the office, where Rose’s shows were taped and where his PBS staff worked, or go somewhere for a drink.

I remember being petrified. I was worried about impressing Rose and nailing the interview, but even more terrified about the prospect of having a drink in a bar rather than sitting down for a formal interview in an office. I’d never heard of anyone at my level attending a first-round interview in a bar or a restaurant. Friends and family members raised the obvious red flags, implying that it was strange to meet over drinks. But most couched their concern by reminding me how cool it was to be presented with such an opportunity.

I showed up at Bloomberg and waited for Rose to finish taping for the day. He and I then took the elevator downstairs and he flagged down a cab. He told me we were going to his apartment because he had to pick up something at home. When we got out of the cab, he instructed me to wait for him in the lobby of his building. He came downstairs about 15 minutes later and we walked into Cipriani, an upscale restaurant located nearby.

The maitre d’ greeted me by saying, “Hello, miss, lovely to see you again,” which was strange because I’d never been there before. My takeaway at the time was that either he mistook me for another young blonde woman Rose frequently brought into the restaurant, or he had grown so accustomed to seeing young women like me walk in with Rose that he couldn’t tell them apart anymore.

The drink occurred without incident, and eventually my friend told me that Rose had hired one of his former interns for the job.

Several months later, I got an email from someone who worked as Rose’s producer at “CBS This Morning.” He said he was leaving his job to go to graduate school and wanted to talk to me about replacing him. He said he more or less operated independently from the rest of the show’s producers. The position would require me to wear many hats, he explained: helping with the morning show, as well as with Rose’s “60 Minutes” responsibilities and other miscellaneous research for his PBS show. It was clear to me that Rose expected his producers to do anything and everything, despite which network they worked for and what their stated job description was. The CBS producer told me that he often traveled with Rose to the Bloomberg offices after the morning show ended, and that he continued working alongside him there.

My gut told me that working for Rose in that capacity would place me in a dangerous silo without any institutional protection, despite the support I’d receive from working for a large company like CBS News and the fact that I would have technically reported to the show’s executive producer, not Rose himself. I reached out again to the woman who had worked as Rose’s assistant and had technically been affiliated with PBS. Sure enough, she advised me to pursue the CBS job, rather than another position on the PBS show, for that very reason.

Rose and I ended up meeting for lunch one Saturday at Le Bilboquet, another restaurant on the Upper East Side that he frequented. He pontificated about how great it would be to work for him, how many opportunities it would provide. I sat there eating my Cajun chicken, smiling in agreement and politely trying to get a word in when I could. I wanted him to think I was conversant and at ease. He asked me to email him with more information about myself, outlining my professional and extracurricular interests. Rose liked to understand what “made people tick,” the CBS producer once told me.

I sent him what he asked for in the following days. He responded, writing, “IMPRESSIVE LETTER.”

“He proceeded to berate me, telling me I was weak and stupid for choosing that option ― that I wasn’t who he thought I was since I clearly didn’t care about the in-depth, meaningful journalism that happens only on his show.”

I also spoke over the phone to a senior producer at CBS. I’d been told she was technically in charge of hiring for the position, but she told me the decision ultimately rested with Rose himself. So I waited.

After I followed up with him directly nearly a month later, Rose asked to meet for dinner at Cipriani at 9 p.m. He was in the middle of prepping for an interview with Al Pacino. “I’m working on Pachino [sic] and don’t have a lot of time but to follow up to your letter,” he wrote in an email.

I met him at the restaurant, expecting to talk about the CBS role. He, perhaps, viewed the dinner as a test of wills or some kind of character assessment. As we ate branzino and drank white wine, he asked whether I’d prefer to work for him at CBS or on his own show. When I answered CBS, he proceeded to berate me, telling me I was weak and stupid for choosing that option ― that I wasn’t who he thought I was since I clearly didn’t care about the in-depth, meaningful journalism that happens only on his show.

He put me in a cab when dinner ended, telling me we would talk soon. I cried the whole way home, beating myself up and feeling as if I had done something wrong. But I couldn’t put my finger on what that could possibly be.

I sought advice from another former assistant of his, who admitted to me that the job was not all it was cracked up to be. She listed various downsides, including Rose’s temper, and implied he had a predatory nature.

Rose was using the power of his position and the tantalizing idea of working for him as a cover to behave inappropriately, my mother told me as I recounted the incident to her. His tactics ― the after-hours meetings, the praise mixed with the aggression ― were just inappropriate enough to make me feel off-balance and let me know who was in charge.

I knew she was right, but I wanted the job so badly that I consulted with the CBS producer on how to proceed. He suggested that I email Rose to reaffirm my interest in the role and to offer to come in and shadow other producers on his PBS show.

I also ended up telling Rose how embarrassed I was by my performance during dinner.

“Your disappointment in my response was palpable as we parted ways tonight, but you were absolutely right,” I wrote. “I would like the opportunity to regain your full respect and confidence.”

I sent him several emails to follow up, which he either didn’t respond to or replied to with vague statements about needing to fill another position before he could consider me. I repeatedly asked if there was anyone else at CBS or on his show to whom I could reach out in order to make the process more official, but he didn’t respond. I decided to abandon ship.

Months later, he sent me an email with the subject line “charlie rose here.” He said he was headed to Paris and that my name “came up.” He was wondering what I was up to. I can’t overstate the satisfaction I took in being able to rebuff him, letting him know I had taken another job.