Like most economists, I am strongly inclined toward free trade. I cringe to see the way it is under attack from both parties during this primary season.

The two populist candidates are the worst offenders. Bernie Sanders, whom I support on many other issues, goes off the rails when it comes to trade. Donald Trump, whose policy views are sometimes too vague to pin down, has made clear-cut opposition to "bad trade deals" a centerpiece of his campaign.

Nor is the pushback from the rest of the field as strong as one might hope. Hillary Clinton has changed her position on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which she supported as Secretary of State, and is running away from her previous support for the North American Free Trade Agreement, which she liked well enough when her husband signed it into law. On the Republican side, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and John Kasich all profess to favor free trade in principle, but when pushed, as they were during last week's Republican debate in Miami, they quickly go on defense, hedging their support for trade with numerous "ifs" and "buts."

Observers think that their opposition to trade has been a key to the strong results for Trump and Sanders in recent primaries, especially in the industrial Midwest. Their joint demonstration of the depth of the anti-trade constituency is likely to have a lasting effect even if neither candidate makes it all the way to the presidency. Still, in many respects, their arguments don't stand up to scrutiny. Let's take a closer look.

Do imports really kill jobs?

Like Trump, Sanders has made the claim that "trade kills jobs" a standard part of his campaign rhetoric. Trade with Mexico, he says, has cost 800,000 jobs and trade with China, millions more.

Politifact has examined the 800,000 job claim and ruled it to be "mostly false." That is hardly surprising, since standard economic theory predicts that trade should have no effect on total employment. In the long run, averaging out business cycle effects, the number of people at work is determined almost entirely by demographic factors -- such as population growth and age structure -- and by social trends like the changing role of women in the labor force.

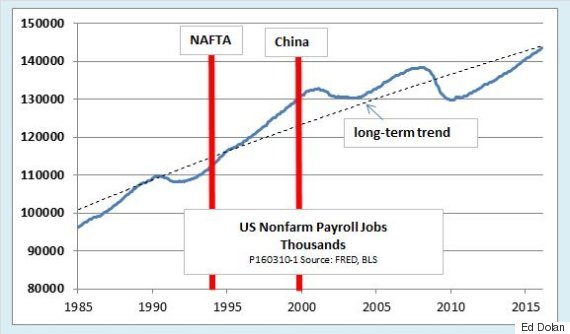

The following chart, which shows job trends over the past thirty years, is consistent with that orthodox conclusion. The red bars show effective dates for NAFTA and normalization of trade with China. As we see, the U.S. economy has added about 50 million jobs since 1985. The pattern of job growth is irregular -- the number of jobs falls during recessions and grows during recoveries -- but as of 2015, the total number of jobs is right where the long-term trend indicates that it ought to be. There are no visible breaks at the red lines. On the contrary, NAFTA came into force near the beginning of one of the greatest job booms in U.S. history.

What standard economic theory does predict is that trade can affect the structure of employment. Countries export things in which they have a comparative advantage and import things in which their trading partners have the advantage. The U.S. has a comparative advantage in aircraft, financial services, farm products and many other goods. American exporters, on the whole, have been hugely successful. Exports as a share of U.S. GDP have grown from 4 percent in 1960 to more than 15 percent today. At the same time, China and Mexico have a comparative advantage in manufactured goods that require low to moderate levels of skill, and their exports to us have grown, too.

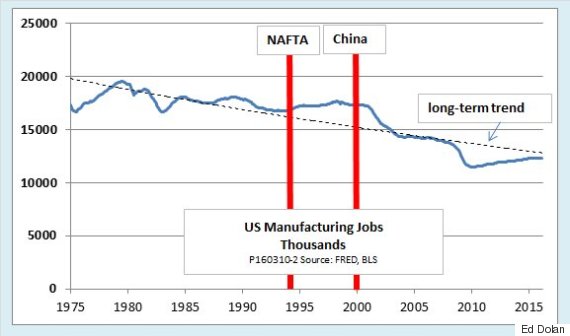

The tendency of trade to draw labor and capital in each country into the production of the things it makes best is the fundamental source of its benefits. Yet, although everyone shares in those benefits through lower prices, some workers lose their jobs and some companies lose their customers to competition from imports. We can see that from the next chart, which shows that U.S. manufacturing employment has declined by a third since its peak in 1979.

Even in this chart, NAFTA has no visible effect. The downward trend in manufacturing jobs was already underway in the 1980s. Although factory jobs increased a bit during the dot-com boom of the 1990s, they fell during the housing boom of the early 2000s, and they have recovered only partially as the economy has shaken off the worst effects of the Great Recession.

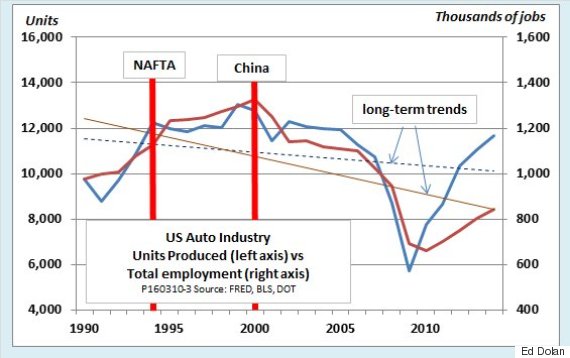

We should remember, though, that trade has not been the only cause of declining manufacturing employment. Rising productivity has also played a role. For example, if we narrow our focus to the auto industry, we see that after a big dip during the recession, U.S. auto output has recovered to its pre-NAFTA level. Yet, because productivity has risen, the number of automotive jobs remains 40 percent below the 1994 level.

Presumably, productivity would have grown even faster if competition from imports had not put downward pressure on autoworkers' wages, easing the pressure for ever-greater automation.

In short, there is a story here about trade and jobs, but it is more nuanced than the one Sanders and Trump tell. Politicians may promise that erecting barriers to trade will bring back both the factory wages and the jobs of the past, but that is fantasy. Protectionism might raise the share of manufacturing in U.S. GDP, but in many cases, the beneficiaries would be robots, not flesh and blood workers. And in the process, the three-quarters of the labor force that would remain in the service sector, many of them working for low pay, would find their standard of living further eroded by higher import prices.

Is money spent on imports "lost"?

Jobs are not the only loss that Trump worries about.

As he put it:

Well, you know, I don't mind trade wars when we're losing $58 billion a year [to Mexico] ... We're losing so much with Mexico and China -- with China, we're losing $500 billion a year. And then people say, "Don't we want to trade?" I don't mind trading, but I don't want to lose $500 billion. I don't want to lose $58 billion.

There is nothing new about this idea. One of the main targets of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, was the doctrine of mercantilism. Among other things, mercantilists argued that if your country brought in more gold than you paid out, you were a winner; if more went out than came in, you were a loser. Trump is a heartfelt mercantilist.

The numbers Trump gives -- $58 billion to Mexico, $500 billion to China -- are trade deficits. They are the difference between what Mexico or China spends on goods exported from the U.S. and what the U.S. spends on goods from those countries. But that money is not "lost" in any normal sense of the word, because U.S. consumers get something in return -- cars, computers, toys for their kids. It makes sense to say, "I lost $50 at poker last night at the Elks Club," but unless you dropped your wallet somewhere in the produce aisle, you wouldn't say, "I lost $50 at the supermarket this morning."

A tariff imposed on Chinese tires saved 1,200 American jobs but cost $1.1 billion in higher prices to American consumers.

When we run a trade deficit with China, we are not losing something -- we are making a choice. Two choices, in fact.

One choice is what kinds of goods to buy and whom to buy them from. If I buy a pair of boots made in China, it is because I like the price, the quality or both. If you tell me, "No, you can't buy those boots. You have to buy those others," I would protest. That would be a real loss -- being forced to buy boots that (in my opinion) give less value for the money.

The other choice reflected in a trade deficit is more subtle. When we run a trade deficit with China, we are, implicitly, making a choice between the present and the future. Right now, running a trade deficit allows us to consume more than we are producing. In return, the Chinese get some money they can use to buy goods from us. But instead of doing so immediately -- in which case, trade in goods would balance -- they take some of our money and invest it in Treasury bills, which they can cash in to buy things from us in the future.

Is it good for Americans, collectively, to consume more than they produce each year? There are credible American economists who think it is not, just as there are Chinese economists who doubt that it is good for China to churn out goods for others, while holding living standards down in order to amass mountains of Treasury bills. One thing is certain, though. We cannot boost the chronic low saving rates of our households and government by starting a trade war with China.

Can we blame it all on currency manipulation?

Another of Trump's favorite themes is to emphasize currency manipulation as a source of trade imbalances. His website tells us:

In a system of truly free trade and floating exchange rates like a Trump administration would support, America's massive trade deficit with China would not persist. On day one of the Trump administration, the U.S. Treasury Department will designate China as a currency manipulator.

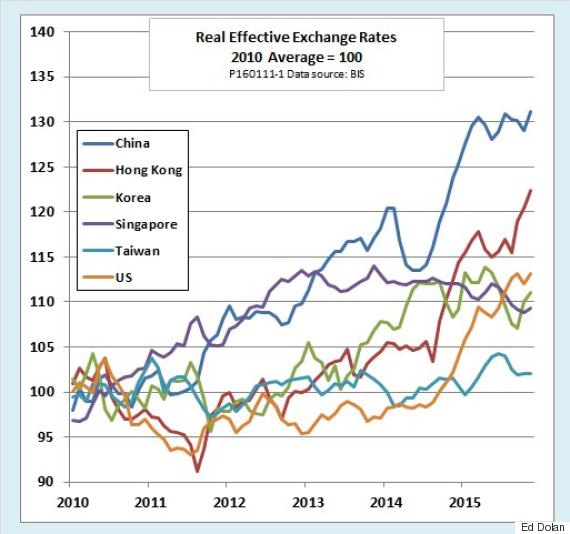

It sounds tough, but the charge that China's policy holds the yuan at an artificially low value is badly out of date. As we see from the following chart, based on data from the Bank for International Settlements, since 2010, China's currency has appreciated by 30 percent, double the rate of appreciation of the dollar and more than Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea or Taiwan.

For conclusive proof that China is not holding its currency at an artificially low value to gain a trade advantage, all we have to do is look at the behavior of its foreign currency reserves. A country that purposely undervalues its currency does so by buying up foreign currency in exchange for its own. In the bad old days, when China's foreign reserves were soaring, the charge of currency manipulation had some credibility. However, since early 2014, China's currency reserves have plunged. They are now more than 20 percent below their peak and falling fast.

The fact is that China is now doing everything in its power to prevent the yuan from depreciating. To the degree it is manipulating at all, it is manipulating its currency upward.

What about the world's poor?

There is one more thing that bothers me about the war on free trade, especially as it is waged by the political left. Bernie Sanders is a progressive. "The issue of wealth and income inequality," he writes, "is the great moral issue of our time, it is the great economic issue of our time and it is the great political issue of our time." But there is one aspect of inequality Sanders stumbles over -- the global inequality between rich and poor nations.

In a recent interview with NBC's Chuck Todd, Sanders agreed that the U.S. has a moral obligation to help people throughout the world, but he struggles to reconcile that aspiration with his anti-trade stance. More typically, he depicts workers in third-world countries as a threat to American workers.

At a rally that I attended in Traverse City, Michigan, Sanders told a story of a visit to a Mexican auto factory sometime in the early 1990s. The factory was shiny and modern, he said, but the workers were making just 25 cents an hour. When he asked to see their homes, he found that they were living in cardboard shacks.

There is one aspect of inequality Sanders stumbles over -- namely, the global inequality between rich and poor nations.

But Sanders leaves out an important part of the story. What do Mexican autoworkers earn today? They reportedly earn $8 to $10 per hour, including benefits. It seems that NAFTA has helped to raise the wages of Mexican autoworkers by as much as forty-fold over twenty years.

It has been the same story everywhere. In 1960, real per capita GDP in South Korea was about $1,500, measured in 2011 U.S. dollars. That is about where Ethiopia is today. By 2010, after a half century as one of the world's preeminent trading nations, per capita GDP in Korea had risen to over $30,000, nearly catching up with Britain. What can a progressive not love about that?

Sanders often says that free trade agreements have produced a "race to the bottom" in wages. He opposes the TPP because it "would bring down our wages by throwing Americans into competition with workers in Vietnam making less than 65 cents an hour." But turn that around, and he means that he wants to slam the door on Vietnamese workers, for whom 65 cents an hour is the first rung on the ladder to the global middle class. In effect, he says we have a moral obligation to help the world's poor but please, don't buy anything from them.

Surely, when Sanders opposes NAFTA and the TPP, he does not really mean that he wants to send Mexican autoworkers back to their cardboard shacks and Vietnamese textile workers back to their rice paddies.

It turns out that under NAFTA, illegal border crossings by Mexicans have slowed dramatically.

I should add that conservatives, too, ought to welcome the growing prosperity of America's trading partners -- Mexico most of all. GOP candidates, Trump foremost among them, talk endlessly about border security. They all agree that we have to do something about the northward flow of immigrants.

But just who is crossing our southern border these days? It turns out that under NAFTA, illegal border crossings by Mexicans have slowed dramatically. A 2014 Pew study shows that as wages and working conditions have improved, the number of border apprehensions of Mexicans illegally entering the U.S. has fallen from a million and a half per year in the 1990s to about a quarter million. Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador -- none of them members of NAFTA -- are now the sources of a majority of illegal immigrants. Another Pew study shows that more Mexicans, legal and illegal, are now returning to their home country from the U.S. each year than are making the trip northward.

What can a conservative not love about a more prosperous southern neighbor?

The bottom line

I can understand Sanders' sympathy with those who have been displaced from good jobs that they thought were secure. But, if we are going to help them, tariffs and other broad protectionist measures are not the way to go. In case after case, economists have found that the costs of such measures are simply too great.

For example, one study found that a tariff imposed on Chinese tires in 2009 saved 1,200 American jobs but cost $1.1 billion in higher prices to American consumers. That comes to more than $800,000 per tire worker's job. And it does not even try to account for the fact that consumers, after paying more for tires, had less to spend on other goods, meaning that American jobs in other sectors were threatened.

It would be far more reasonable to employ direct forms of aid. Retraining, adjustment assistance to workers or employers, income support or wage subsidies are some of the possible remedies. None would come close to costing $800,000 per job.

Some commentators tell us not to get excited. Presidential candidates go protectionist in every election season, they say, and then support free trade once they are in office. They point out that President Obama, who imposed the tire tariffs and bragged about them in the 2012 election year, later negotiated the TPP and saw the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (first signed by George W. Bush) through its implementation phase.

Let's hope that, no matter whom we elect, those optimists are right.

Follow Dolan's blog at www.economonitor.com.