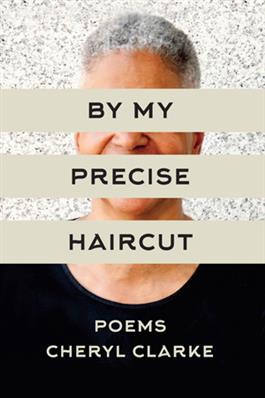

Cheryl Clarke's new poetry collection is By My Precise Haircut (The Word Works Press, 2016). By My Precise Haircut is the winner of the Hilary Tham Capital Competition, judged by Kimiko Hahn. Clarke is the author of Narratives: poems in the tradition of black women (1982), Living As A Lesbian (1986), Humid Pitch (1989), Experimental Love (1993), the critical study, After Mecca: Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement (Rutgers Press, 2005), and The Days of Good Looks: Prose and Poetry 1980-2005 (Carroll and Graf, 2006).

Clarke has written many essays over the years relevant to the black queer community. "Lesbianism: an act of resistance," which first appeared in the iconic This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color (Anzaldúa and Moraga, eds., 1982) and "The Failure to Transform: Homophobia in the Black Community," which was published in the equally iconic Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (Smith, ed., 1984) continue to be favorites among readers. Clarke is a scholar of Audre Lorde and continues to write about Lorde's work. She retired from Rutgers University in July 2013 after forty-one years of teaching and administration. With Barbara J. Balliet, her partner of twenty-four years, she is the co-owner of Blenheim Hill Books in Hobart, NY, the Book Village of the Catskills. Clarke, Balliet, and Clarke's sister, Breena Clarke, organize the annual Book Village Festival of Women Writers in Hobart.

This interview with Cheryl Clarke is a wide-ranging conversation about all the impressive work over her writing career. It is divided into three parts.

Part I

Julie R. Enszer: Cheryl, let's start with By My Precise Haircut. One of the things that strikes me about By My Precise Haircut is the way you write history. You gesture to big history, history that we find in history books, for example the march of black women in the poem "one million." You combine this "big history" with insights from lived experience; in "one million," you observe that at the march HIV and AIDS are not mentioned. How do you think about your relationship to history as a poet?

Cheryl Clarke: History is in my bones, since I became aware of black people as subjects of it. So, I think about it and I don't think about it. What compels me about history are its ironies--the same thing that compels me about literature--the ironies. How HIV/AIDS affects black women, whom the one million black women are having a march on behalf of, and no one talks about how the pandemic has ravaged poor black women and poor black families and communities, striking and infecting people all under fifty. But, as I think about it, maybe the Million Black Women March was "on behalf of" black men. With history the ironies occur; with literature you create them like I did with "one million." In the poem "Elegy on Twelve Years A Slave," I was struck by how the film, Twelve Years A Slave, captured the vulnerability and fragility of black people as did Northup's narrative. In the slave narrative, Northup describes Patsy's strength and pride in her work though she was so vulnerable to the cruel whims of both her slave owners, and how defeated she became after that ruthless beating administered by Solomon and, finally, the slave master; all so brutally captured on film. The film was very close to the narrative, which is why I say "text to sprocket." I suppose I was moved to write a poem about it because it starred two Africans--one West African and one East African, though by the time Northup was enslaved, there were not very many Africans being brought over because the African Slave trade was officially over in 1808. But as we know, a black person could be sold over and over and over again. So, another irony that two continental Africans were "playing" friends, so intimate (yet distant) that Patsy can ask Solomon to help her kill herself. Ironies not lost on the director and screenwriter, I'm sure.

JRE: Let's continue a little more with your sense of history and your sense of place. It has been a while since you lived in Washington, DC, but the city still has a hold on you. It fills the imaginary of your poetry. What makes the landscape of Washington so significant to you as opposed to the other spaces that now shape your daily life?

CC: Washington, D.C. is more colorful, cultural, historical, and snobbish than any place I have ever lived since I left it in 1969. The towns I have lived in since pale beside D.C.--and that is fine. Its history as a stopping off place for black Southern migrants, as my mother's people were--from North Carolina--is also enchanting. I enjoyed its liminal Southern culture. The Howard Theater was another cultural/historical place in Washington, where I saw many cultural icons, e.g., Pearl Bailey's Revue, Miles Davis, Betty Carter, Nancy Wilson, Martha and the Vandellas, Isley Brothers, Jerry Butler, to name a few. I witnessed segregation falling by the wayside in the early '60's, but certainly remember its vestiges. I remember the picketing of Woolworth's. I remember bragging to my mother that I crossed the picket line at Woolworth's, and she said, "Don't ever cross a picket line when people are doing something for you." She was a staunch unionist. I, of course, remember the March on Washington, which I attended with my parents. Also, it is the blackest town I have ever lived in; the greater number of black people who give that town its cultural vitality. I went to college there--Howard--and that still fills my imaginary, which is not always a good place--my imaginary--because of how it often tends toward the nostalgic. I tried to avoid the nostalgic in the references to and poems about D.C. Readers will have to be the judge whether I am successful. I was not a gay person there socially until I was in my thirties. and attended the first Lesbian and Gay March on Washington. I attended many other gay rights marches in Washington. I saw the AIDS Quilt on the monument grounds, and that was such a magnificent and moving experience. A man sat with his legs drawn under him at the edge of one of the panels, sobbing. I had the same rush of emotion seeing Maya Lin's Vietnam Veterans War Memorial, family members and friends pointing out and invoking the names of lost loved ones. Jewelle Gomez and I even attended the 20th anniversary of the March on Washington in 1983--the one at which Audre Lorde was asked to speak at the last minute against the protests of Walter Fauntroy--one of D.C.'s black bourgeois homophobic preachers, who became the first Congressional Delegate to represent D.C. in 1971, succeeded by Eleanor Holmes Norton in 1990. I remember wearing a "Proud to be Gay" button at that March and going up to a vendor to buy a Coke. And the man who waited on me saw that button and said, in near disgust and surprise, "Gay." The other man said to him, "Just wait on her and shut up." Both were black. And I tell you it was hot as hell that day as only D.C. can be.

JRE: Yes, I know how hot D.C can be, having lived in College Park for years. But now, I'd like to talk for a moment about poetic process. Like many writers, you work diligently on your poems. Can you talk about the writing process behind one of the poems in the new collection?

CC: This is not my favorite question. I can easily be pretentious. "Oh, my process." Is it like my "precise haircut"? Probably. I have my hair cut once a month, very short with a slow fade on the sides. And leave it until it gets unruly. Then, I go and have it clipped and cut. So, what I am trying to make a conceit of is revision. I get an idea for a poem. I attempt writing it. (I lose far more ideas than I put down. This is disappointing.) Maybe look at and think about "Some Dead," one of the newer poems. I was moved to write it a year ago by a headline in the Sunday Times Magazine about one of the anniversaries of the Bosnian genocide: "Mass Graves Uncovered. The Dead Still Haunt the Living." I began to think of that Baby Suggs quip in Morrison's Beloved, "Not a house in the country ain't packed to its rafters with some dead negro's grief." Her emphasis on "some." The very inspecificity of "some" is countered by the totality of "every," creating a wonderful, though tragic paradox. Of course, I thought of the title of Lorde's 1986 book of poems, Our Dead Behind Us. The dead are always part of our past and they are always behind us pushing us forward, making us occupy the frontlines. This is the haunting. And so, I began to think of historical genocidal events--slavery, the Holocaust, corrective murders of gender nonconforming people, the rape of Muslim "matrons" by Islamophobic people the world over. These issues brought the poem together, if you think it is "together." You see where I am going. The "'some' dead" are very specific dead who were killed or have died for who they were then and who we are today.

JRE: Death is a fitting transition to love and sex: Your earlier works, Experimental Love and Living As a Lesbian taught me about sex and desire and eroticism. I remember reading them in the humid Detroit summers in my apartment in Palmer Park. Two poems in By My Precise Haircut intimate the centrality of love and sex to your work and both of them are near the end of the collection. Could you talk a little bit about "working my way" a gorgeous tribute to Billie Holiday and butch-femme lesbian sexuality.

CC: "working my way" is one of the older poems, going back to the late '90's. The homage to Billie Holiday came very late in its life--not that Lady Day was a lesbian, though I'm told she liked pretty women and was not unfamiliar with those whom she called, "lezzies." Originally, it was "working my way back to you" instead of "Billie Holiday." Then, one evening during some intense revising, the idea to supplant the second person with one of our great icons of woman-love and woman music. Billie Holiday is a muse for me. She became a great aesthetic teacher for me throughout the '70's, and she'd been dead since 1959 by then. Billie is always someone I can return to. To learn from. I am happy that you feel it is a "gorgeous tribute" to "butch-femme." We could use more tributes to butch-femme. More tributes to love between (among) women with its many roles. The poems, "Next (French film after the Euro)," "reprise (for Ginsburg)," "bald woman," "Wings," and "working my way" have rather explicit or direct references to sexuality (bodies and acts), yes. They don't all occur at the end. Two open the collection. Let's face it, I haven't been explicit since Experimental Love was published twenty-three years ago. Others are taking up that challenge now. And I'm always happy to help.

JRE: "working my way" ends with that killer couplet: "throat deep/right to my ears." I feel like we should all take a moment to self-pleasure.

CC: You sound like Donne. "Self murther." My friend, poet and serial fiction writer Esther Cohen gave the "right." Go on. Knock yourself out. Pleasure or 'murther' yourself.

JRE: Then there is the concluding poem, "wings". It opens, "Sex waits in the wings, second, third, / or tenth after writing." Tell me about this poem, particularly its powerful concluding line, which ends the collection.

CC: This is a critique of or homage to the place I assign sex--direct unmitigated/unmediated pleasurable fucking with whomever and whatever and wherever--in my process and living. Sex waits--no matter who/what women and men fuck, do, or say. Sometimes it waits too long. Sometimes it waits past reclaiming, meaning we have to look for new expressions. I'm not on that 'new expressions' journey, Julie.

Physical sex would often be the last thing on my mind. But I hold onto desire always. And poetry helps and makes much desire possible where sex falls short.

And so we see here, in this poem, "wings," sex waits upon what other fascinations to which we give precedence and preference. And we (I) run from all that lip-smacking juicy-ness to some safer drier terrain. But then there is always the less troublesome terrain of self-pleasure. A fitting way to end the collection, right?

JRE: And a fitting way to end the first part of our interview. Stay tuned for Part II.

For more information about Cheryl Clarke, visit her website:

www.cherylclarkepoet.com.