He was one of the world's leading chess players in the 1950s and 1960s and the Yugoslav player of the 20th century. After nearly seven decades playing chess, the legendary grandmaster Svetozar Gligoric turned to music.

Last month, shortly after his 88th birthday, Gligoric presented his first music album in Belgrade.

How I survived the 20th century is a collection of 12 compositions, mostly jazz, blues and rap. Gliga or Gligo, as his friends call him, wrote the music and texts and invited some known Serbian musicians to perform with him. The central theme of his work is expressed in the song Life is all we have. Gligoric pointed out the similarity between music and chess: "Each note is like a chess move and from these elements you create your own architecture within known rules."

Music was always Gligoric's passion. He loved it even before he knew how to read or write. He had an enormous collection of musical recordings and sometimes played guitar, but it was only at the age of 80 when he decided to get actively involved a began to take music theory and piano lessons. The album is a remarkable achievement for a man who spent most of his life in chess.

Gligoric won the Yugoslav championship 12 times and belonged among the world's Top Ten for two decades (1950s and 1960s). He played in 15 chess olympiads, mostly on the first board. During his tenure, Yugoslavia won one gold, six silver and five bronze medals. He won five Zonal tournaments and took part in two Candidates tournaments, in Zurich in 1953 and in Yugoslavia in 1959. In 1967 he qualified for the Candidates matches from the Interzonal tournament in Sousse, Tunisia. Gligoric rarely turned down an invitation to an international tournament, circled the globe and amassed an impressive record.

His style of play was classical: he cherished a strong pawn center, a pair of bishops and did not like to play passively. He was a big threat to Soviet players and defeated the world champions Mikhail Botvinnik, Vassily Smyslov, Mikhail Tal and Tigran Petrosian more than once. He also scored victories against Max Euwe and Bobby Fischer. He didn't believe in psychological warfare in chess. "I play against pieces," he said simply and made it the title of his biography.

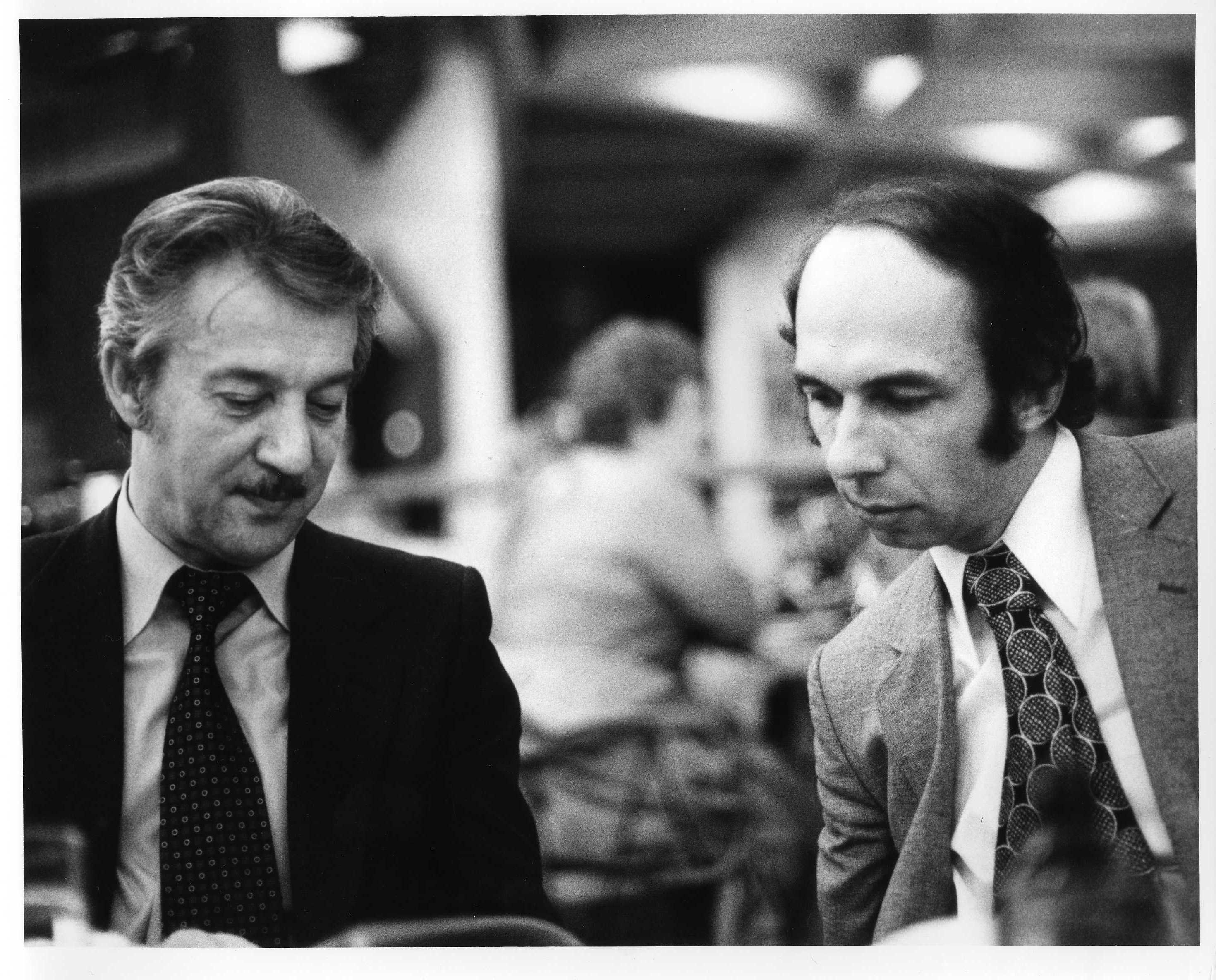

Although he was 20 years older, he treated our generation well. He became a friend and mentor to young Bobby Fischer. In 1978 he ran for the post of FIDE president because he wanted Bobby to return to chess. In 1979, I invited Gligoric to be the chief arbiter at the Tournament of Stars in Montreal. Gligo not only fulfilled his duty, but wrote notes to the games. The players joined in, creating a unique tournament bulletin with commentaries appearing the next day.

Working with Gligo in Montreal in 1979

Gligoric was a prolific chess journalist and author. His book Fischer vs. Spassky, The Chess Match of the Century came out the day after the match finished and sold 400,000 copies.

It is not an accident that the games in his biography are sorted according to openings. Gligo was one of the most knowledgeable opening experts. His monthly theoretical articles were translated into many languages. Many strong players benefitted from Gligo's opening ideas, including Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov.

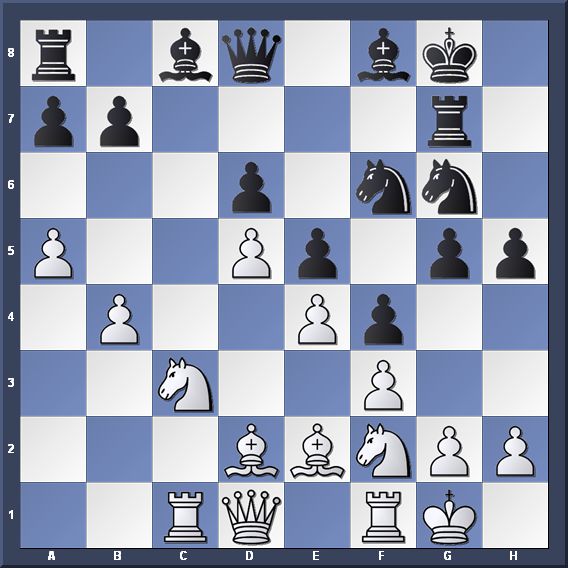

He was always well prepared for the games. If he got caught by surprise, he used his instinct to get out of difficulties. The following King's Indian game against one of the world's best defenders, Tigran Petrosian, is a good example.

The knight sacrifice is of a positional nature, far from clear. It resembles sacrifices of Gligo's second Dragoljub Velimirovic, leaving the verdict up in the air. It was played in the Rovinj-Zagreb tournament in 1970. The knowledge of this game helped me five years later.

Petrosian - Gligoric

Rovinj/Zagreb 1970

1.c4 g6 2.Nf3 Bg7 3.d4 Nf6 4.Nc3 0-0 5.e4 d6 6.Be2 e5 7.0-0 Nc6 8.d5 Ne7

9.b4

(The Bayonet Attack was the main reason why even the most stubborn King's Indian players gave up on the defense. Gligoric's legacy is the incredibly effective kingside set-up in the Mar del Plata variation 9.Ne1 Nd7 10.Nd3. It premiered in the Argentinian resort in 1953 and it is still on fire more than a half century later. Here is the original: 9.Ne1 Nd7 10.Nd3 f5 11.f3 f4 12.Bd2 Nf6 13.b4 g5 14.c5 h5 15.Nf2 Ng6 16.Rc1 Rf7! Gligo's invention. 17.cxd6 cxd6 18.a4 Bf8! 19.a5 Rg7! A beautiful combination of attack and defense.

20.h3 Nh8! Threatening to maneuver his knight via f7 to h6 and break through with g5-g4. 21.Nb5 g4 22.fxg4 hxg4 23.hxg4 a6 24.Na3 Bd7 25.Nc4 Rc8 26.Nb6 Rxc1 27.Bxc1 Be8 28.Ba3 Nf7 29.Qc2 Nh6 30.g5 Rxg5 31.Rc1 Rg3 32.Bb2 Nfg4 33.Nxg4 Nxg4 34.Bxg4 Rxg4 35.Qf2 Bg6 36.Rc4 Qe7 37.Bc3 Qh7 38.Qe2 Rh4 39.Kf2 f3 40.Qe3 Rf4 41.gxf3 Qh2+ 42.Ke1 Qh1+ 43.Ke2 Bh5 44.Kd2 Rxf3 45.Qg5+ Bg7 46.Kc2 Rf2+ 47.Bd2 Qd1+ 48.Kc3 Qa1+ White resigned, Najdorf - Gligoric, Mar del Plata 1953.)

9...Nh5 10.Nd2 ("Up to the present game Petrosian kept this idea secret. It was usual to play 10.g3, taking the f4 square away from the black knight, but it costs white a tempo and weakens the kingside. For example 10... 10...f5 11.Ng5 Nf6 12.f3 h6 13.Ne6 Bxe6 14.dxe6 f4 15.b5 fxg3 16.hxg3 Qc8! 17.Nd5 Qxe6 18.Nxc7 Qh3, threatening perpetual check, Pachman-Taimanov 1964.

Petrosian's move increases the queenside pressure in extra-quick time. Black is no longer able to block the queenside, as after 9.Nd2 c5, so white's king's knight can play an important role there," Gligoric explains.

10.Re1 became popular 25 years later and it is still the main line.)

10...Nf4

("The knight is strongly placed on this square but it can't stay there forever. Petrosian's idea is based on the assessment that black has spent two moves on this maneuver and the knight is standing in the way of the black kingside pawn mass." - Gligoric)

11.a4 ("The bishop can't immediately run away to f3 since after 11.Bf3 Nd3 12.Ba3 a5! white's dark bishop has no good place to hide." - Gligoric) 11...f5

("At this moment I had the feeling that I was in grave danger of being outplayed on the queenside so all my moves were motivated by my hurry to carry out a counter-action that would neutralize white's initiative. Perhaps the simple 11...Nxe2+ was also playable, clearing the way for the black pawns." - Gligoric )

12.Bf3 ("Until here black has been fighting in the dark, not knowing exactly the essence of white's plan, and his last move came as a small psychological shock that lasted some five minutes. Should I have taken the light bishop earlier? Because now it is too late. After 12.c5 I wanted to reduce white's menacing pressure by playing 12... 12...fxe4 (12...Nxe2+) 13.Ndxe4 Nf5," writes Gligoric.) 12...g5! ("After the initial surprise, I spent twenty minutes searching for the best solution at this critical moment of the battle. The move played, threatening 13...g4, is probably the only sound solution. Black weakens his ligth squares, but speeds up his action on the kingside, which is important to maintain balance. After 12...Nd3? 13.Ba3 the dark bishop is active, safely hidden behind the a-pawn, which was the idea of white's previous move and 13... 13...a5 can be met by14.bxa5 with advantage. The variation 12...fxe4 13.Ndxe4 Nf5 14.g3 was much slower than the move I played." - Gligoric) 13.exf5 Nxf5 (Threatening 14...Nh4.)

14.g3!? (Weakening the kingside. After 14.Nde4 comes 14...Nh4, but 14.Be4 was a good blockading move.)

14...Nd4! ("The knight sacrifice seemed to me the only good reaction at this point. It is a positionally active continuation and it should solve the problem of maintaining the balance. After 14...Ng6 the black pieces would be pushed back and white would not only have a spacial advantage but also superiority on the light squares," Gligoric says.

The game Keene - Kavalek, Teeside 1975, showed that black doesn't need to retreat or sacrifice the knight and can play 14...Nh3+ 15.Kg2 Qd7! indirectly protecting the knight on h3.

Leading the bishop-queen battery with the queen is not common, but I had the opportunity of playing it with the white pieces against Wolfgang Pietsch and once Bent Larsen used it against me.

16.Nb3

[Trying to control the square d4. After 16.Kxh3 Ne3+ 17.g4 Nxd1 black wins; 16.Bg4 is met by 16...Nxf2! 17.Kxf2 Nd4+ 18.Bf3 g4; and 16.Be4 g4 17.Nb3 h5 gives black a good play.] 16...Nd4 17.Nxd4 exd4 18.Nb5 c6! 19.Na3

Keene goes to the edge, leaving black with a sizeable advantage. After 19.Nxd4 comes 19...Rxf3 20.Kxf3 Qg4+ 21.Ke3 c5.]

19...Rxf3!? I could not resist the temptation to sacrifice the exchange, but the simple 19...Be5 solidifies black's gains.

20.Qxf3 g4 The noose around the white king gets tighter. Black only needs to prepare a deadly bishop check on the square e4. Keene tried 21.Qb3 Qe7! (Preventing 22.f3.) 22.Ra2? Bf5 23.f3 White is doing all he can to prevent an outright defeat, but it is not good enough. Black now has several ways to win the game:

a) 23...Be4! Andrew Martin's suggestions in "The Main Line King's Indian" by John Nunn and Graham Burgess 24.dxc6 bxc6 25.Nb1 Bxf3+ 26.Rxf3 Qe1 27.Rf1 Qe4+ 28.Rf3 Rf8 29.Bf4 Nxf4+ (29...gxf3+ 30.Kxh3 Qe6+ 31.g4 Rxf4-+) 30.gxf4 gxf3+-+;

b) 23...Rf8! suggested by Deep Fritz 12, is even better, leaving the threats 24...Be4 or 24...gxf3+ 25.Rxf3 Be4 open. After 24.fxg4 Be4+ 25.Kxh3 Rxf1 and black wins.;

I played 23...d3 24.fxg4 Qe4+ 25.Rf3 Ng1? [Showing off. The knight leap landed me in trouble. I missed 25...Qxg4! and black should win.] 26.Qxd3 Qxd3 27.Rxd3 Bxd3 28.Kxg1 cxd5 29.cxd5 Re8 draw, Keene-Kavalek, Teesside 1975.)

15.gxf4 (Petrosian has to accept the sacrifice because after 15.Bg4 Bxg4 16.Qxg4 h5 17.Qd1 Nh3+ 18.Kg2 g4 19.f3 Qd7 black is better.) 15...Nxf3+ (Removing one of the defenders seems more logical than 15...exf4.)

16.Qxf3?! (Gligoric thought that 16.Nxf3!? was more cautious. It was the right move. Black has to juggle with 16... 16...g4!? , for example 17.Nd2 exf4 18.Nde4 Bf5!? 19.Ra3 Qe8! 20.f3 Qg6 21.Kh1 [Or 21.Bxf4 gxf3+ 22.Ng3 Bg4 23.Qd2 Rae8.] 21...Rae8 22.Rg1 Rxe4! [22...g3?! 23.Bxf4 Bxe4 24.Nxe4 Rxf4 25.Rxg3 Qh6 26.Ra2 Kf8 27.Rag2 Be5 28.Qc1±] 23.Nxe4 Bxe4 24.Rg2 [24.fxe4? Qxe4+ 25.Rg2 f3 26.Rf2 Bd4 wins for black.] 24...Bf5 25.Bxf4 h5 hoping to survive.)

16...g4 17.Qh1? (A strange decision. Petrosian burries his queen in the corner, limiting his own king. The Armenian grandmaster was known to predict danger many moves ahead, but I am not sure he was such a great defender once his opponent got his attack rolling. Gligoric expected 17.Qd3 and hoped to keep equality with 17...Bf5, for example 18.Nce4 exf4 19.Rb1 f3 20.Bb2 Qh4 with compensation; or 18.Nde4 exf4 19.f3 [After 19.Bxf4 Bxe4 20.Qxe4 Bxc3 21.Ra3 Qf6 black is fine.] 19...gxf3! [Not 19...g3 20.Bxf4! and white wins.] 20.Rxf3 Bxc3 21.Qxc3 Bxe4 22.Rxf4 Qg5+ 23.Qg3 Qxg3+ 24.hxg3 with even chances.

The alternative 17.Qd1 exf4 18.Nde4 Bf5 has been discussed above.)

17...exf4 18.Bb2 (The computer engines prefer to consolidate with 18.Nde4 Bf5 19.Bd2 for example: 19...Qe8 20.h4 Qe5 21.h5 Qd4 22.h6 Be5 23.Rae1 Qxc4 24.Qh4 Kh8 with roughly equal chances.) 18...Bf5 (Black could have locked the white queen immediately with 18...f3.)

19.Rfe1 f3 20.Nde4 Qh4 (Preparing to bring the rook from a8 to the battle, the move also gives an impression that black intends to lock the white queen with Qh4-h3. Petrosian gets nervous and worsens his position.)

21.h3? Petrosian tries to free his queen, but he opens his king up to danger. Other moves keep black in charge: 21.Ng3 Bg6 ; or 21.Nd1 Bxb2 22.Nxb2 Rae8 23.Ng3 Bg6 white is playing without queen and black threatens 24...Qf5.) 21...Be5! (It's over now. Black has a winning attack.) 22.Re3 gxh3 23.Qxf3 Bg4! (According to Gligoric, this is more energetic than 23...Bxe4 24.Rxe4 Rxf3 25.Rxh4 Bxc3 26.Bxc3 Rxc3.)

24.Qh1 h2+ 25.Kg2 (After 25.Kf1 Rf3! wins.) 25...Qh5! ("It took me some time to find this fine maneuver which is the most efficient way of continuing the attack and battle for the light f3 and h3 squares around the white king. White's reply is forced because he has to protect the f3 square," Gligoric says.) 26.Nd2 Bd4!? ("Attacking the main defender - the rook protects the third rank." - Gligoric. However, 26...Qg5! is swifter, for example 27.Rxe5 [27.Kf1? Qxe3! wins.] 27...Qxd2 wins.)

27.Qe1 (After 27.Rae1? Bh3+! 28.Rxh3 [28.Kxh2 Rxf2+ 29.Kg1 Rxd2 wins.] 28...Rxf2+ 29.Kg3 Qg5 mates.)

27...Rae8!? (Gligo brings the last piece into battle, but he could have finished the game more efficiently with 27...Bxe3!, for example 28.Qxe3 Rf3! 29.Nxf3 Qh3+ 30.Kh1 Bxf3+ wins; or 28.fxe3 Bh3+ 29.Kh1 Bg2+! 30.Kxg2 h1Q+ 31.Qxh1 Qg4+ 32.Kh2 Rf2+ 33.Qg2 Qxg2 mate.) 28.Nce4 (After 28.Kh1 comes 28... 28...Rxe3! 29.fxe3 Bf3+ 30.Nxf3 Qxf3+ 31.Kxh2 Be5+ 32.Kg1 Qg4+ 33.Kh1 Qh3+ 34.Kg1 Qh2 mate.) 28...Bxb2 29.Rg3 Be5 (The straightforward 29...Bxa1! 30.Qxa1 Rxe4 31.Nxe4 Rf3 32.Nd2 Rxg3+ 33.fxg3 Qh6 also wins.) 30.Raa3 (After 30.f3 Bxg3 31.Qxg3 Rxe4! 32.fxe4 Rf7 33.Rh1 Qh6 34.Nf1 Rg7 black wins.) 30...Kh8 31.Kh1 Rg8 32.Qf1 Bxg3 33.Rxg3? (Speeds up the end, but black also wins either after 33.Nxg3 Qh6; or 33.fxg3 Rgf8 34.Qa1+ Re5!) 33...Rxe4! (After 34.Nxe4 Bf3+ wins.) White resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.

SOLUTIONS TO KING TUT PUZZLES:

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.