A quick and simple test can identify concussions in children as young as 5 with an astonishing rate of success, according to a new study. So why aren’t people talking about it more?

The King-Devick test, as it’s called, was originally developed in the 1970s as a way to detect dyslexia. But a new study out of New York University's Langone Concussion Center and published in the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology has found convincing evidence that it can also detect when athletes of all ages suffer a concussion -- and that it can do so even better than other commonly used tests.

What’s most notable about the King-Devick test is its simplicity: It requires only a stopwatch (read: smartphone) and a few printed-out pieces of paper, and it can be administered by someone with no professional medical experience whatsoever in less than two minutes.

Yes, that means moms and dads can do it themselves whenever they’re concerned about that last hit their child took on the field.

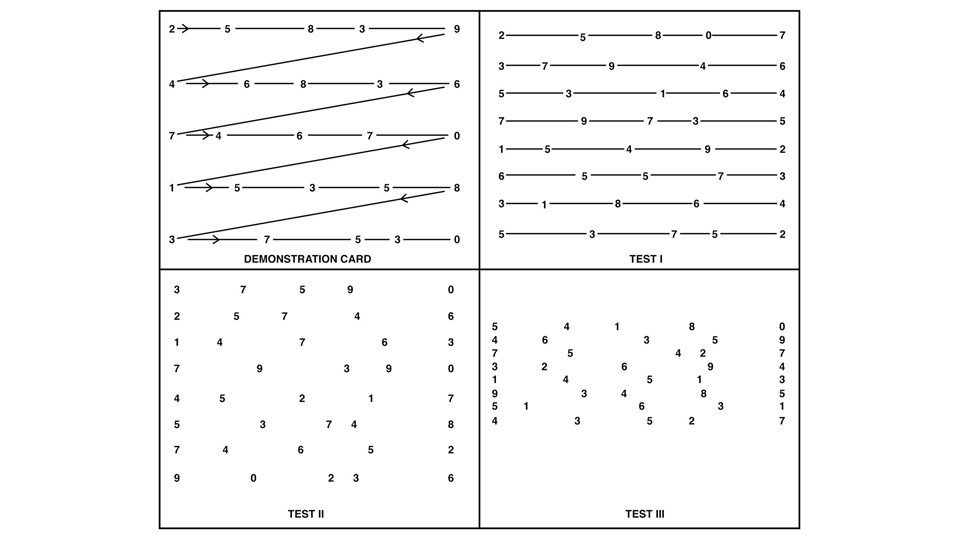

The test requires children to read a series of numbers from left to right off of three different pieces of paper as fast as they can, while someone else times them for each one. Those times are then tallied together and compared to the time it took the child to complete the test earlier in the season.

Top left corner: The order in which numbers are supposed to be read. The other three patterns are the three separate tests.

If a child takes longer than the baseline time by even a few seconds, there’s reason for concern. Researchers found that young athletes who were concussed took 5.2 seconds longer on average to finish the test compared to their baseline time. Meanwhile, young athletes who were not concussed actually finished 6.4 seconds faster, perhaps because childhood is a phase of such rapid brain development.

Simple as it may sound, the test actually does a better job of detecting concussions (with a 92 percent success rate) than two better-known methods: a "timed tandem gait test" similar to a walk-the-line test (87 percent), and a cognitive test known as the Standardized Assessment of Concussion (68 percent).

The researchers who conducted the study believe this is because the King-Devick test assesses eyesight. Roughly half of the brain’s circuits are dedicated to our ability to see, according to previous research cited in the study. So a test that emphasizes that part of our mind will offer hints as to the brain's overall health.

You can see how the test works at around 00:40 in this video.

The test was taken by 89 NCAA athletes at NYU and Long Island University, and by 243 5-to-17-year-olds who played ice hockey and lacrosse.

“Our findings in children and collegiate athletes show how a simple vision test can aid in [the] diagnosis of concussion at all levels of sport,” Steve Galetta, one of the study’s authors and a professor of ophthalmology at NYU Langone, said in a release Thursday. “Adding the King-Devick test to the sideline assessment of student athletes following a head injury can eliminate the guesswork for coaches and parents when deciding whether or not a student should return to play.”

As many as 3.9 million sports-related concussions occur every year in the United States, according to emergency-room data compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and cited in the NYU Langone release. In fact, the tally could very well be even higher, given the number of concussions that are ignored or that don’t result in hospital visits.

A spokesman for NYU Langone Medical Center emphasized that the authors of the study have no financial ties to the King-Devick testing company. “We’ve never even accepted as much as a cup of coffee from the entrepreneurs,” Laura Balcer, co-director of the NYU Langone Concussion Center and a professor of neurology, ophthalmology and population health at NYU Langone, told The Huffington Post over the phone.

While the success rate of the King-Devick test is impressive, Balcer emphasized to HuffPost that if possible, parents should have their child perform all three of the above-mentioned concussion tests when he or she takes a hard hit.

The reason could not be more clear. In tandem, the three tests can detect concussions at a rate that is truly hard to believe -- 100 percent.