BEIJING -- What do China's "war on pollution" and campaign against corruption have in common? They've both placed China's coal and oil empires in their crosshairs, and they're firing away.

Over the past two years anti-corruption squads have investigated dozens of high-ranking officials in coal and oil bureaucracies, with the latest detention announced Monday night: The vice chairman of China National Petroleum Corp., Liao Yongyuan, was placed under investigation for "serious violations of discipline," Communist Party-speak for corruption. In China, the announcement of corruption investigations virtually guarantees an eventual conviction.

When he assumed power at the end of 2012, Chinese President Xi Jinping vowed to purge the Chinese Communist Party of rampant corruption, and he's since executed an anti-corruption campaign that has decimated patronage networks ranging from the coal industry to the People's Liberation Army. As that anti-corruption campaign continued to gather steam in 2014, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang responded to the putrid haze blanketing Beijing by publicly "declaring war" on air pollution.

Beijing's National Stadium, aka the Bird's Nest, on clear and polluted days in 2014.

Beijing's National Stadium, aka the Bird's Nest, on clear and polluted days in 2014.

Though the parallel campaigns haven't been explicitly linked by Chinese leadership, the drives to clean up China's skies and the Communist Party leadership have both hit hardest in the country's vast coal and oil empires. Over the past two years coal-rich provinces and CNPC, the fourth-largest company in the world by revenue, have respectively racked up some of the highest tallies of corruption detentions. At the same time, the central government has imposed strikingly ambitious targets for slashing coal consumption.

China incinerates nearly as much coal as the rest of the world combined, and fumes from low-quality gasoline contribute to air pollution that chokes the skies of northern China. Last year the mayor of Beijing described his own city as "unlivable" because of the pollution.

China's two major state-owned oil companies -- Sinopec and CNPC (also known as PetroChina) -- came in for a scathing treatment in a viral pollution documentary released earlier this month. The film, "Under the Dome" -- which was largely blocked from the Internet by government censors after one week -- accuses the firms of stymying pollution controls and milking their duopoly position for corrupt profits.

The film was produced by former Chinese state television journalist Chai Jing, and China's new minister of Environmental Protection compared it to Silent Spring, the book credited with helping launch environmentalism in the U.S. in the 1960s. In the film, an anonymous official with China's main economic planning agency claims that the oil firms even threatened to cut off gasoline supplies if their demands weren't met.

"You can't control them," the official from China's National Development and Reform Commission said. "Say you have an only child and this child is picking up some bad behaviors. As his mother, what can you do? All you can do is give him one good beating, but you can't beat him every day."

This year corruption inspectors have vowed to deliver such beatings to corrupt officials at state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the bureaucratic and often monopolistic businesses that dominate key sectors like telecommunications, media and energy. SOEs intermingle government responsibilities and business functions, but they've also shown the ability to resist or twist directives from the central government. Monday's investigation announcements included Liao from CNPC and Chairman Xu Jianyi from FAW, one of China's largest state-owned automakers.

"Each [SOE] tends to be a mini empire," professor Dali Yang, who researches Chinese politics at the University of Chicago, told The WorldPost. "They have become very powerful vested interests in the Chinese system, so anti-corruption is not only useful in fighting against corruption but ... makes it possible for Xi's agenda, for the agenda of the Communist Party, to be carried out, to be obeyed."

Academics have long debated the true motivation for Xi's corruption crackdown. Is it a move to clean up the party from within? A front for knocking off political rivals? A strategy to clear the way for ambitious reforms?

"All of the above and then some," said Yang.

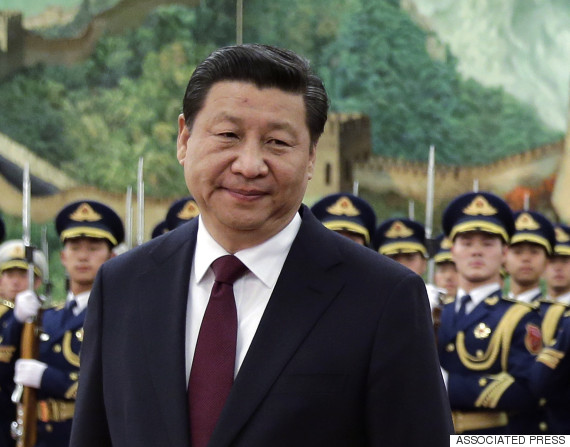

Chinese President Xi Jinping has launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign, but critics question the real motives behind the crackdown.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign, but critics question the real motives behind the crackdown.

Just two years into office, Xi has already earned a reputation as the most powerful Chinese leader in decades. He has waged an extensive campaign to limit domestic dissent, and has put anti-corruption, major economic reforms and pollution alleviation at the center of his public agenda.

2014 proved to be a landmark year for curbing both corruption and pollution. As coal-intensive industries slumped and strict pollution controls started to bite, China saw its first fall in both coal use and carbon emissions in over 15 years. China's air was made marginally more breathable, but coal-dependent northern provinces fell into deep economic ruts. Coal powerhouse Shanxi province barely achieved half of its 9 percent growth target.

At the same time, anti-corruption investigators had a heyday raking through Shanxi's political circles: Last year the province reportedly ranked first in its percentage of high officials to be probed for corruption, with nearly one-third of the the province's party committee coming under investigation. Last week, the governor of Shanxi said coal empires are deeply entwined with the province's corruption cases.

But no bureaucracy has proved as ripe for investigators as CNPC. According to Chinese media reports, more than 45 CNPC employees and officials have come under investigation. Online news portal Sina Finance reports that CNPC has even instituted a policy to deal with a wave of secret detentions: High-ranking employees all have designated back-ups who will take over duties if they have gone missing for a set period of time.

Much of that activity has reportedly swirled around the patronage networks of Zhou Yongkang, the ex-security czar who last year became the highest-ranking official to come under investigation since the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949. Zhou spent decades rising through the ranks of China's oil bureaucracy, serving as the Chinese Communist Party secretary of CNPC before climbing into the Politburo Standing Committee, the most powerful body in China.

Zhou Yongkang spent decades in state oil before his political ascent and subsequent fall.

Zhou Yongkang spent decades in state oil before his political ascent and subsequent fall.

Anti-corruption investigators have spent over two years detaining and questioning many of Zhou's associates, and on Monday, Liao became the latest in a long line of CNPC officials to fall. Liao had reportedly been nicknamed CNPC's "Northwest Tiger" for his performance exploiting oil fields in China's far western deserts.

His dismissal came just weeks after the spread of the pollution documentary "Under the Dome," in which the filmmaker argues that CNPC and Sinopec essentially set their own fuel standards, and that their duopoly breeds corruption and stifles innovation in cleaner-burning natural gas.

At a press conference on Sunday marking the end of China's annual National People's Congress, The WorldPost asked Premier Li Keqiang if he agreed with the now-banned film's depiction of Sinopec and CNPC as obstructing environmental reforms. Li didn't mention the film or state oil companies in his reply, but called for continued vigilance in combating pollution.

"No one should use his power to meddle with law enforcement in this regard," Li said.

Thirty-two hours later, the Chinese Communist Party's anti-corruption commission issued a short notice on its website announcing that CNPC's vice chairman had been placed under investigation.