"If you can't find me," Meng Zhaoguo said over a cell phone whose signal faded from its isolation, "Just head to the last house on the logging commune lane. Or ask anyone who's around." Everyone knows the first Chinese person to allegedly be abducted by aliens.

With its surging economy, China is summiting once-unseen heights in world rankings: millions of English speakers, almost the most millionaires and actually the least frugal tourists. Yet despite being slightly larger in area than the United States with four times as many people, China trails far behind when it comes to visitors from outer space. To date, only one Chinese person -- lumberjack Meng Zhaoguo -- claims to have slept with one.

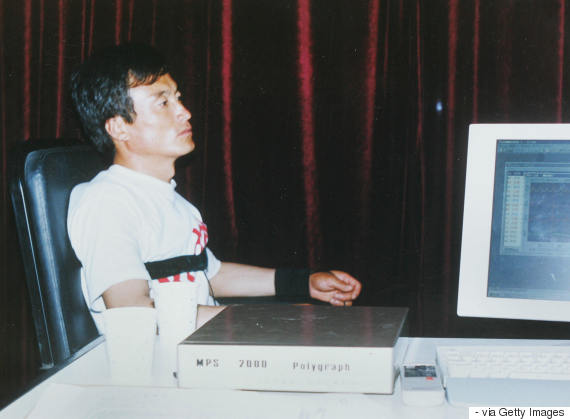

Meng Zhaoguo, a rural worker from northeast China's Wuchang city, taking a lie detector test in Beijing. I first visited Meng at his home on the Red Flag Logging Commune, set among the remains of a forest in China's far northeast, an area historically known as Manchuria. Chinese characterize Northeasterners as big-hearted, industrious and sometimes a bit touched in the head. So it was not a shock when the nation's first person claiming interstellar relations came from here. In 2003, I traveled over a winding, ice-covered, one-lane road through the forest to meet him.

On the commune, Meng lived in a two-room timber frame house he had built with his own hands. Bare yellow light bulbs dropped from the ceiling, and there was no phone -- or cell reception. But a big-screen Sony television filled one end of the room.

"Out here, it only picks up two channels," he said. "So it's a waste of money, but I didn't buy it. A businessman brought it, after he heard about my story." Another visitor, from Malaysia, had brought him a cow. "I sold that," Meng told me. "Cows cost money to take care of. What am I going to do with a cow out here?"

We stepped outside, boots crunching snow, and faced the Dragon Mountains, veiled in purple mist as the day's light faded. Meng said that on a night much like this in 1994, he saw a metallic glint shimmer off those peaks.

"I thought a helicopter had crashed, so I set out to scavenge for scrap." He made it to the lip of a valley, spying the wreckage in the distance, when "Foom! Something hit me square in the forehead and knocked me out."

He awoke at home, he told me, with no memory of how he got there. A few nights later he woke to find himself floating above his bed. As his wife slumbered beneath him, a 10-foot-tall, 6-fingered alien woman with thighs coated in braided hair straddled his waist. Meng and the alien copulated for 40 minutes.

"She then disappeared through the wall and I floated back down to bed. She left me with this." He undid his trousers to reveal a two-inch-long jagged mark that he insisted bore only a coincidental resemblance to a scar resulting from a slipped stroke of a saw.

I asked him to draw the creature, and he took my pen and tore off a sheet from a roll of rough, unbleached paper. To my surprise, I recognized the alien. As he made tiny x's on the alien's inner thighs, I realized Meng was sketching a hairy cousin of the Michelin Man. His smiling, puffy white face waved from atop an auto repair shop at the base of Red Flag Logging Commune. I thought of that, and the empty crates of Five Star beer stacked just outside Meng's front door, and the remote loneliness of a Northeast winter.

But Meng told the story calmly, not in a desperate or pleading tone, cajoling the listener to believe. I kept my deductions internal, and he suggested we go outside with his kids and light the fireworks I had brought for them. That night I slept fitfully on Meng's bed, while he took the couch.

Two Michelin men (Bibendums) are displayed ahead of the general shareholders' meeting at the headquarters of the French tyre-making group Michelin in Clermont-Ferrand, central France on May 16, 2014. (THIERRY ZOCCOLAN/AFP/Getty Images)

"'In 60 years, on a distant planet, the son of a Chinese peasant will be born.'"

In China, the government monitors faith in anything but the Communist Party, but an expression of belief in extraterrestrials is permitted, as it falls under the purview of astronomy, and the "scientific socialism" the party supports. A UFOlogy journal has a circulation of 400,000, and the UFO associations across China boast a collective 50,000 members. China UFO Research Center has held annual conferences before splintering -- as organized groups of believers tend to do -- into rival factions. The president of the Beijing branch is a retired foreign ministry official who, after seeing a UFO, believes aliens live among us.

After Meng's story circulated among enthusiasts, the media came calling, leading to his appearance in national newspapers and on television. He was even the subject of a debated Wikipedia page, which listed different versions of his story, including being taken to the aliens' home planet of Jupiter, and "ongoing harassment" from the extraterrestrials.

"Journalists look for discrepancies in my story," he told me the next morning at his house. "I get tired of telling it. In the end, I'm just a peasant."

Meng added that a month after the alien had visited him, he again awoke to find his body passing through the world map hanging over his bed. He levitated through the stratosphere and into a spaceship, where aliens circled him.

"They said in Chinese, but with a heavy accent so it was hard for me to understand at first, that they were refugees. Like me, they wanted to escape their former lives, so they left their dying home."

That echoed the tales of many Chinese migrants, including Meng's desire to move his family off the defunct Red Flag Logging Commune.

Meng asked to see his alien paramour, the one with braided hair on her inner thighs.

"'Impossible,' they replied. But then they said something that made me hopeful. 'In 60 years, on a distant planet, the son of a Chinese peasant will be born.'"

This was a stroke of genius: Meng had introduced Chinese class-consciousness to outer space. (He also made sure few people who heard his tale today would be around to see its proof). And while my Northeastern-born wife declared his story a lesson in the "Art of Northeastern Bullshitting," the story was also an example of self-invention, transporting Meng, his wife and children from the last house on a logging commune lane to a metropolitan campus after a university official reached out and offered him a job.

"Humans, if we have never seen something with our own eyes, naturally doubt that it exists, or that life could be that way. I was the first to be brave enough to say: 'I saw that.'"

When I sought him out there when researching my book -- "In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China" -- in Harbin city a decade later, he again told me to head to the last building on the lane, or just ask anyone where he was. Everyone knew the first Chinese person to be abducted by aliens.

There he stood, in full grin. "I am very happy to work here," he said. "It's quiet. I'm in charge of the boiler and watch the steam pipes." It was a better job than felling trees, which were now protected. His coworkers at Red Flag Logging Commune had either left or stayed to farm soybeans.

Meng wore a clean white tunic, slacks and loafers, with short black hair pushed neatly to the side. He looked thinner, healthier and just as earnest as before. But he was tired of retelling what became known as the "Meng Zhaoguo Incident." Talking with him is how I imagined it would be to interview a former adult film star embarrassed about his past. "When students say they recognize me from television," he said, "I tell them that was someone else who looks like me."

But his notoriety had landed this job.

"A friend told me about it, and when I came for the interview, the boss had seen me on the news," he said. "The college provides an apartment with heating, my wife and daughter are working on campus as well, and my son attends a good Harbin middle school. He's studying English. Life is better for him here than in the forest."

When he retold the tale over lunch in Harbin, only one detail had changed: "I asked the aliens if I would see my child," he added. "They said yes. But they would not tell me where."

I made a joke but Meng didn't laugh.

"Once, humans believed that the earth was flat," he said. "Even a decade ago, people would not believe that a cell phone could work. Humans, if we have never seen something with our own eyes, naturally doubt that it exists, or that life could be that way. I was the first to be brave enough to say: 'I saw that.'

"But you know," Meng said, nodding collegially. He looked directly into my glasses, which in the bright northeast sunlight reflected his own face, and concluded: "When you live up here, you see strange phenomena all the time."

Michael Meyer is the author of "In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China."