In February, a federal nutrition panel made headlines with new recommendations regarding cholesterol.

To better understand exactly what they said, and -- more importantly -- what it means to you, I'm happy to turn this space over to two experts in this field.

Linda Van Horn, Ph.D., is a registered dietitian and professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine. She also is a member of the American Heart Association's Nutrition Committee.

Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, M.D., is chair of the department of preventive medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine. He helped develop the 10-year heart attack and stroke risk assessment calculator published by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

---

You probably saw items in the news recently suggesting that eating foods high in cholesterol may be OK, and maybe even that you can eat all of the egg (yolks) you want. Well, as usual, it's not really that simple, and some media reports substantially misrepresented the conclusions of the new report.

You probably saw items in the news recently suggesting that eating foods high in cholesterol may be OK, and maybe even that you can eat all of the egg (yolks) you want. Well, as usual, it's not really that simple, and some media reports substantially misrepresented the conclusions of the new report.

The 2015 U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) recently submitted its report to the Secretaries of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) in preparation for development of new U.S. Dietary Guidelines.

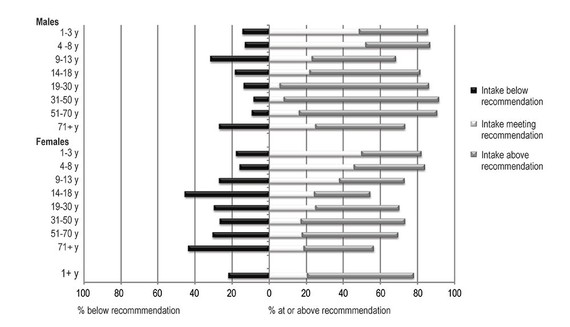

A primary goal of dietary guidelines is to provide food-based recommendations for meeting the nutrient needs of healthy individuals according to age, sex, life stage and other group categories. The DGAC carefully reviews national data related to nutrient and food intake as well as the biochemical measures of nutritional status in order to determine nutrients that are over- or under-consumed by all or some of the U.S. population.

A primary goal of dietary guidelines is to provide food-based recommendations for meeting the nutrient needs of healthy individuals according to age, sex, life stage and other group categories. The DGAC carefully reviews national data related to nutrient and food intake as well as the biochemical measures of nutritional status in order to determine nutrients that are over- or under-consumed by all or some of the U.S. population.

If a particular nutrient is consumed above the level established by the Institute of Medicine as the "Tolerable Upper Limit of Intake," it is deemed a "nutrient of concern" because in excess it contributes to some adverse health condition. Examples of current nutrients of concern include sodium and saturated fat because the vast majority of the population consumes too much of these nutrients compared to recommendations.

So what is new with dietary cholesterol intake?

First, please remember that we are not talking about blood levels of total or "bad" cholesterol (LDL-cholesterol). Nothing has changed regarding our understanding that blood levels of bad cholesterol are a major risk factor for heart attacks. High blood cholesterol plays a key biological role in the development of the artery plaques that cause heart attacks. High dietary saturated fat intake can raise blood cholesterol.

But when it comes to dietary cholesterol, context matters regarding how it might affect your blood levels of cholesterol (what we really care about). In many previous iterations of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, it was recommended that dietary cholesterol intake be restricted to no more than 300 mg/day. This recommendation was based on substantial previous evidence that excessive dietary cholesterol intake, especially when accompanied by excess saturated fat, could contribute directly to elevating blood levels of bad (LDL) cholesterol, leading to heart disease. These data were obtained at a time when Americans on average were eating much more saturated fat in their diet, so extra amounts of dietary cholesterol in the diet were difficult for the liver to process, leading to higher levels in the blood.

In their review of the totality of evidence on dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, the 2015 DGAC determined that, based on current population data, there was no conclusive relationship established between dietary cholesterol intake and blood cholesterol levels, thereby suspending dietary cholesterol as a "nutrient of concern." This finding was in agreement with the report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology published in 2013.

Unfortunately, there was widespread misinterpretation, or maybe wishful thinking, regarding the DGAC's statement.

Many consumers and media alike decided this meant that they were free to eat all the high cholesterol-containing foods they wanted and there was no reason to be concerned about eating a diet high in dietary cholesterol. This is not the case.

There is no biologic requirement for dietary cholesterol since our own body's production is sufficient to meet its needs. It is also important to note that dietary cholesterol only comes from animal products, since it takes a liver to make cholesterol. Often these foods are also high in saturated fats.

So, what has changed?

Generally, Americans are eating somewhat less saturated fat than they did two decades ago (but still far too much). This means many of us can handle intake of foods higher in dietary cholesterol without affecting our blood levels of cholesterol. Eating a few egg yolks within a diet low in saturated fat may be fine. That's not true for everyone though, so you should check with your doctor about whether or not it is safe to liberalize your intake of cholesterol-containing foods a bit.

We should not let the pendulum swing all the way back to where it was earlier, when saturated fat and dietary cholesterol intakes were very high. The current U.S. mean intake of dietary cholesterol is 273 mg/day. This is well below the earlier recommendation to consume less than 300 mg/day that had previously been determined from rigorous research on diet and cholesterol. As we know, though, those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it.

Left unchecked, people who resume eating large amounts of dietary cholesterol from meats, dairy, and other high saturated fat-containing animal products may risk increasing their own and the population's LDL cholesterol levels. This could reverse the progress in cardiovascular risk reduction that has been made during the last three decades when dietary guideline-driven reductions in cholesterol and saturated fat intake, and the population levels of blood cholesterol, decreased dramatically along with the cardiovascular mortality rate.

The take-home is that just because dietary cholesterol is no longer a "nutrient of concern," it does not mean we should forget about the problems it can cause. An apt analogy is that just because we know dark chocolate has some heart-health benefits, it does not mean people should eat 10 bars a day.