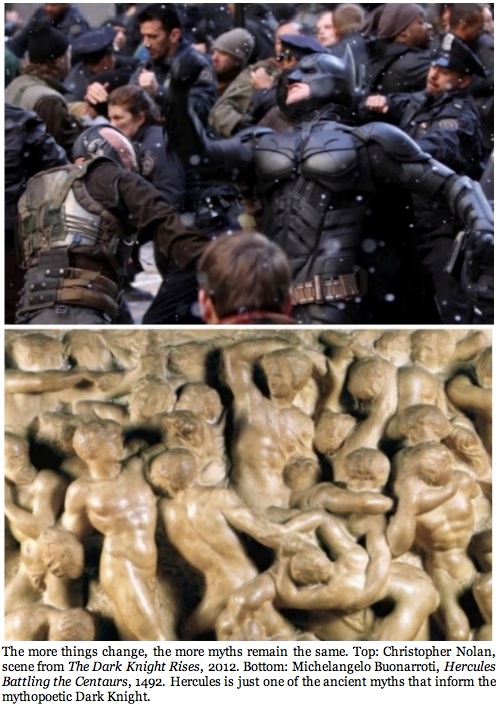

*On 7/24/12 the author added the correlating photos of the battle scene from Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight Rises and Michelangelo's Battle of Hercules and the Centaurs. Originally only a photo of the battle scene with Batman was shown.

If there is a myth that seems to be shared by most of the modern, classical and tribal societies of the world, it is the myth of the hero's descent into hell. This is the kind of myth that is meant to test all the strengths, faith, and values that a society takes stock in -- or at least to convince the members of the society that those values have long ago been put to the test, and like the hero who returns from hell in triumph, we should feel confident that our values can endure the severest tests. Of all the ancient myths to survive, albeit transformed by modernity, the descent into hell perseveres best in societies that skeptically retest the myth for themselves, whether through some collective crisis that draws all its members, no matter how divided, together to weather a collective storm (or war), or by each individual's endurance in his and her own descent into a private hell. Unlike the myth, not all those tested emerge from their hells alive. We saw this most tragically Friday morning in receiving the news from Aurora, Colorado, that a deranged gunman opened fire into a midnight screening of The Dark Knight Rises, killing and wounding dozens of people, including children, in a bizarre mimicry of the movie to be shown onscreen.

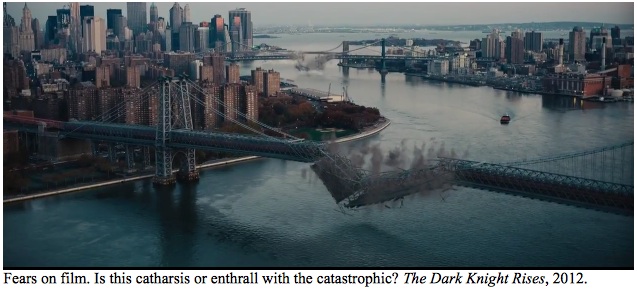

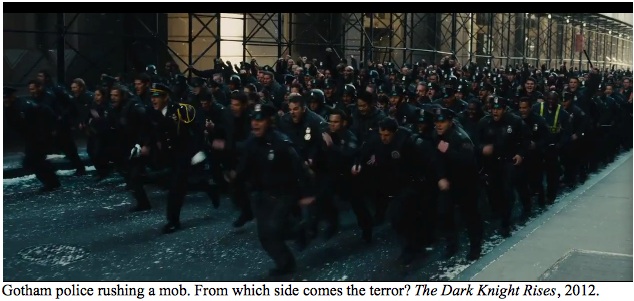

The terror that rises within us with news of such a tragic yet obviously planned event in synchronicity with a form of entertainment and art, confirms that our onscreen myths have substance in the real world. But the terror also reminds us that before we immerse ourselves in such a bleak and socially reflective summer "entertainment" as The Dark Knight Rises, we should all take a moment to reacquaint ourselves with the purpose and power of myth and myth making. An understanding of myth in our skeptical society has become an all-too remote intellectual endeavor, despite that it is an endeavor that has sustained rewards for even the most novice contemplator. For mainstream civilization today, it takes a blockbuster entertainment such as The Dark Knight Rises to gather and focus the attention and reflection of an enormous and diverse modern populace into an otherwise collective mindset, as if they were no more than some primitive story circle gathered around a camp fire to hear tell of the legends shining down on them from the heavenly constellations.

But first we modern skeptics should all come to understand that the scheme and fabric of human deportment we call myth is neither the deluded and debunked thinking that colloquial usage often purports it to be. Nor is it some anachronistic belief system that historians of myth once tried to confine it to. Myth embodies the living ideologies, faiths and value systems that can take form as much in science, economics, medicine, government, law, and industry as it does in religions, philosophies, arts and narratives. Myths are protean in their ability to take all shapes and forms, but most strategically when taking forms that affect whole societies and civilizations by extrapolating real life, common and collective experiences into exalted, yet everyday narratives and iconographies that maintain a continuum between the real world of nature and humankind. Arguably the most significant myths a society entertains are those that support and organize the powers that dictate the ways that we govern, regulate, communicate, educate, and perpetuate social behavior.

In its great expanse of influence, myth is as much an art form as it is a pragmatic and cathartic conversion of the signifiers and symbols of crisis and power. Myth converts all manner of public and psychic components, both the toxins and healing tonics, the catastrophes and saving graces alike, into pragmatic if spectacular warnings and wisdoms meant for all. In recent decades, myth has increasingly become recognized as a vital, capacious and versatile model for reflecting or embodying our most challenging and confrontational problems, human dynamics and societal values -- as capable of effecting social and political change as in perpetuating the status quo. Yet, besides having great ethical and ideological currency in the most contemporary and thriving cultures, myth has its deepest roots extending to historical, prehistorical, even primordial forms the world over.

Myth can achieve all this because it is derived from our most deeply rooted emotional and neurological structure and is thereby conveyed socially as a kind of language. By 'language,' I mean the kind of communication that transcends linguistic and iconographic signs and symbols specific to a given society to permeate to levels of our conscious and subconscious activities and attitudes to the point that we all come to think in universal terms. In the larger social context, myth is an invaluable and active agent in the dissemination and reinforcement of power, whether it be by a myth's ratification of the status quo or its confrontation to, and rearrangement of it. In this pragmatic and socialized view of myth, cultures are built up from and reinforced by fugitive myths -- those ideas and things we don't recognize as myths; things we consider to be as real as we are, while working in the social subconscious to uphold, or bring dissent upon, authorities and institutions -- be they scientific, economic, racial, political or sexual. Well-established myths, such as the leader or the hero, are so seductive and sought out that they dominate our thinking and life choices often without our awareness.

Mythopoetics, on the other hand, as the conjoining of the words 'myth' and 'poetics' conveys, introduce a relatively new, creative mythic status into the equation of social power, one that, however stabilizing its proponents idealize it to be, is inevitably destabilizing to some sector of the status quo for its attempt to effect dissent against, and a redistribution of, conventional and traditional power and industry. Think of how conservatives who invest in the myth of national defense became confronted by a cinematic myth such as James Cameron's 2009 film, Avatar, whereby an elaborate liberal, green movement upholds the myth of global warming while denouncing the sprawl of the military-industrial complex. This is mythopoetics at its most left-liberal political and activist dissemination.

Throughout the last century, we've found that when a mainstream culture begins issuing mythopoetical forms (in films, literature, art, the internet) that honor myths which for centuries have been in disrepute, it's a sign that a notoriously censorial social order is slowly coming to its end. But when the new myths promoted are mythopoetic hybrids of the fantastic and the proscribed, then usually an entire belief system is being overturned for its complicity with historic suppression. Since the 1930s, both subcultural and mainstream myths have taken form in a profusion of spectacular activist myths like the comic book superheroes fighting against fascism during the Second World War. By the 1970s and 1980s, we saw gay and lesbian-identified vampires, multiracial mutants, feminist cyborgs, ecological elementals, and the disenfranchised ethnic-alien menace. In an era when the bottom line and the top dollar closed in on the arts and entertainment industries, and when obsolete cultural distinctions between "high" and "low" cultural forms became increasingly obsolete, we began to see more and more popular artists in sci-fi, horror, and superhero genres posturing as challengers of the status quo, and intent on forcing society to become more inclusive through the compelling, if easy and entertaining tropes of the fantastic, technological, and hormonal myths that have the greatest impact on societal reorganization through hedonistic entertainment.

In this fashion, mythopoetics today operate as it did in the days of Homer, Ovid, and Aesop -- stimulating thought, belief, values, and action from among the core of human ideals. If today's mythopoetics are more consciously and deliberately disseminated through artistic and narrative models rather than faith-based systems, it is both because civilization has become better schooled in the discourse of myth -- the forms, structures, and languages that channel all manner of entertainment, art, ideology, ethics, and science -- and because the modern media has become a multi-billion dollar mythopoetic industry open to eager and hungry novices worldwide. Unlike education, which imparts articulated, lucid and direct meaning shared with a specific aim and discipline to enhance life, mainstream mythopoetics is a particularly beguiling form of enculturation, one which is more akin to oblique values seeping through a mental culture and absorbed, both unconsciously and consciously, through enjoyment of simple and popular tropes -- those hooks that snare us for all their compelling, if succinct, blend of truth and artifice. Despite recognizing myth as being no more than a possible reflection of reality comprised of iconography and narrative, we invest our newest myths with all the values we assume to be operative and newly urgent in the real world of today.

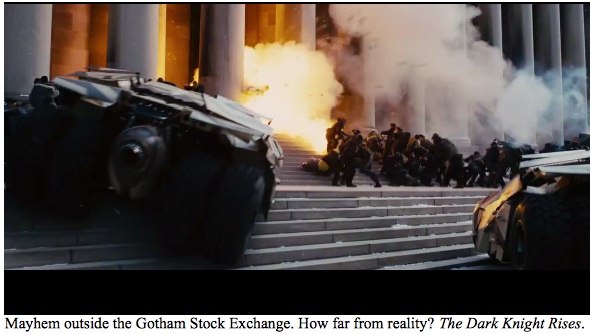

For all the discussion ensuing about the grip that Christopher Nolan's final installment of the Dark Knight Trilogy will hold on the movie industry and its international audiences, the greater currency that the film offers its audience pertains to the directors's regurgitation of current social, political, and economic dissent circling the globe. This much information comes from Nolan himself, who has indicated that current events inform the conflicts seen onscreen in his farewell direction of the Batman. It's the kind of speculation that gives every indication that The Dark Knight Trilogy has consciously ascended to the mythological realm of universal meaning that many critics and astute viewers saw in the two earlier installments -- in this case a myth of warning on imminent population growth, white collar crime and blue collar reactions to it, the disproportion of wealth, and our acceptance of a political culture groomed in deception.

I write that mythopoetics introduce a "relatively new" status into the mix; in fact, it can be a "new" that is actually quite old -- ancient, even primordial. In the case of The Dark Knight Rises, and of Christopher Nolan's entire Dark Knight Trilogy, this mythos puts a new spin on what must happen to pent up reserves of languishing energy when it is threatened by that energy's leakage into entropy. The extremes in action that come into play when human energy erupts from frustration and blockage, rather than when it is allowed to flow unfettered, is the result of that energy having been wasted, or brought to a literal death. This wasted loss of energy that we call entropy, when manifested in humans, becomes the core of all the myths told in the mold of the hero vs. the villain. Energy and entropy may be real forces, but in that they are also abstract concepts, they become the kind of seething myths bursting with ferocity when taking human form. For all its cinematic power (and budget!), The Dark Knight Rises simplifies and universalizes as basically, conveniently and suitably for our age as the battle between Apollo and Python was made familiar for the classical Greeks, or as the battle between Re and Aphophis suited the Middle Kingdom Egyptians.

Such exhilarating battle myths not only have the effect of enticing the imagination, but of impelling their audiences to look for manifestations of such myths in life, however consciously or unconsciously. In Nolan's case, The Dark Knight Trilogy revives the creation vs. destruction myths of old, those that pose superheroic contests that in their time stood in for a lack of physical theories of energy and entropy explaining to unscientific populations the experiences we have of things in flux and stasis, the cause of beginnings and ends. This isn't to say that modern science isn't comprised of myths. As the recent international attention heaped on the Cern experiments to "ascertain" (read mythologize) the existence of the elusive Higgs particle confirms, hypothetical science is arguably the most prodigiously and extravagantly mythopoetic enterprise ever devised, given its dearth of empirical observation to correlate to its postulates. (But more on this in a future article.)

In this context, the Dark Knight Trilogy has proven itself exceedingly relevant as a new generation's premier myth of terror and destruction, the kind that readies people for real catastrophes and hostilities to come. Of course, myth always kept societies prepared for war and devastation, which is why mythological retellings in contemporary dress so often appear both compelling and fresh. But Nolan transcends "compelling" and "fresh" by making his mythopoetics socially significant. With the exception of the Alien films franchise, particularly those starring Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley in her reticent combat with the race of parasite xenomorphs, there is no more savage a cinematic mythos than that composing the Dark Knight Trilogy. Nolan has made the trilogy this decade's premiere myth of entropy, doing what it took four brilliant directors -- Ridley Scott, James Cameron, David Fincher, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet, along with Weaver -- to make the Alien franchise the premier cinematic mythos of entropy for the 1980s and 1990s. But then Nolan had the help of three exceedingly talented actors, Christian Bale, Heath Ledger, and now Tom Hardy.

But whereas the Alien parasite became the metaphor for the invader, whether it stands in for the AIDS retrovirus ravaging human cells, or some moralistic commentary on social prejudice fearful of the emerging and "different" challengers to the status quo that many critics saw the Aliens to stand in for -- those homosexuals, feminist women, multiracial and ethnic "intruders" on the status quo infiltrating the mainstream of Western society with their "foreign" religious faiths and politics. Relevant to the last year, the metaphor of difference and opposition of the chaotic mobs in The Dark Knight Rises are clearly to be identified with those who carry the specter of class warfare openly into the street to be fought out. In the Occupier Generations' terms, the scenarios unfolding in Rises parallel the opposing 1 and 99 percents. Never mind that in the film, the 99 percent have evolved into a criminal class.

Don't mistake this for what some irony-blind commentators have too quickly deemed to be Christopher Nolan's "reactionary" answer to the Occupiers. Remember Mad Max? The Matrix underground? The cyber punk fugitives of William Gibson, Bruce Sterling and Pat Cadigan novels? This is Nolan's 2012's version of cyberpunk taken well beyond the stimulants and steroids that virtually reshaped the 1980s post-apocalyptic visions. This is a brewing revolution seething out of the entropic gases of social myths about, and intent on, taking back control of the world from the obscenely wealthy. Like the aliens and cyborgs of two and three decades ago, Nolan's criminal mob is no more than a desperate representation of our own limbic systems -- that part of the human nervous system inherited from lizards -- swelling up in alarm and reaction to the sight of our potential devolution and extinction. Except that the Dark Knight Rises warns of another impending social disease: the kind that is first signaled by money drying up in the general populace. Pour on top of this economic drought the aberrant and catastrophic climate change sweeping the world, and we see in our future the history of civilizations and populations in quick and severe decline. Hoarding by the few and polluting by the many both make the rich richer, while leading to decline, de-sublimation, and ultimately to the extreme conflicts and eventual extinctions that have informed the mythopoetic narratives and art of millennia.

On the opposite end of the spectrum looms that mythopoetic optimist and King of the World, James Cameron, who bestowed us just three years ago with one of the brightest myths to grace the cinematic and virtual screens. It's ironic that Cameron, creator of Avatar, also spawned the darkest and most savage film of the 1980s -- arguably of cinematic history -- in the 1986 film Aliens. Twenty years later, Cameron chose to redeem himself with the eco-shamanism of Avatar, a world view intended to salvage whatever is left of the generosity and beauty of humanity. Cameron's mythology of the Na'vi people, a population indigenous to a moon named Pandora situated light years from earth, has obvious dorsal roots extending back to Neolithic and Paleolithic societies on earth -- while above the ground his story reflects the present day jungle of an American political system locked in a contest between utopian ideals and dystopian fears that anthropologists warn us are leading to the extinction of tribal peoples. Cameron's virtual jungle, in fact, takes on multiple meanings, not least of which count the threats that the American and other militarily- and industrially-developed nations pose to the real-earth prototypes for the Na'vi.

Because myth is both deeply engrained in the human condition and relatively simple in its structure, it instantly attracts and congeals whatever social and political urgency is closest at hand. Whatever the real outcome of such political events, such is the absorptive power of myth to compel us, as we watch Pandora's sacred and ancient trees toppling under technocratic might of American entrepreneurs, causing them to snap and crash to the ground. Summoning to mind Avatar's Na'vi population alongside the mobs of The Dark Knight Rises may seem akin to watching twin stars -- one dark and hidden within a vacuum hole, the other blazingly lighting up the heavens. The image of their competition between the two universes for the same gravity necessary to each's existence reminds us that all the world's battles are waged in the name of survival -- though of the two films, only Avatar shows the existential dawn after the battle. But then even at the end of Aliens, Cameron makes the vacuum of outer space appear safe and serene, however falsely, as his successor David Fincher reveals.

Another mythopoetic irony literally coming to light is reflected from Nolan's 2002 film, Insomnia, which is set in the calendar of northern Alaska's six months of perpetual light, and exhibiting in the story the disabilities that are the effect of too much light. It's the interchange between the settings of Insomnia and Avatar with the seemingly endless nights of the Dark Knight and Alien franchises that convey just how insightful and versatile both Nolan and Cameron are, that they can switch mythically between the opposing motifs of light and darkness so totally, yet effectively. But then anyone who photographs or paints knows just how perceptually and metaphorically interdependent and gradated are light and darkness -- just as are their allegorically-opposed characters. This should come as no surprise to storytellers, especially those attuned to the sky's role in the mythopoetic impulse. For what are the Dark Knight and Aliens but the direct descendants of the ancient myths that evolved from the stories crafted by shamans and astrologers to memorialize the competition of the constellations in their race to the highest point in the sky, only to be deposed in the fall that must follow the circular procession around the pole star, and after it, the successions of night and day. This circularity of night and day, the stars and planets, can even so many millennia later be seen in the new myths reflecting the struggles that seemingly model how good never triumphs over evil for more than the day that intercedes on the night. This is why mythologists see in such films comprising the Alien and Dark Knight franchises a terrain of language already travelled by the Greek myths of Demeter and Orpheus; by the Egyptian Osiris and Isis; by the African Wanjiru; the Mesopotamian Inanna; the Japanese Izanagi; the Blackfoot Kutoyis; the Indian Gautama; and the Semitic Jesus -- all who are said to have descended into the entropic underworld of the dead yet triumphantly lived to be eternally celebrated as myth.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.