Visiting a popular concert hall for the first time some years ago, I was lucky to have a fairly genial host whom I'll call Luddy. He guided me patiently through the obtuse and unfriendly ticketing procedure at the "Will Call" window where I felt rather like I was visiting a sort of bland theatrical version of the Department of Motor Vehicles. When I commented that it hardly seemed the promoters wanted to make buying tickets desirable, my guide explained the situation away by means of a sort of denial mechanism, never seeming to lose interest in pointing out the gargantuan monument to culture the concert hall itself represented.

Although I loved the music I heard that evening, I was struck at the time by how matter-of-factly my guide dismissed my observation that concerts might not be easy to figure out for a first-timer. And he took it for granted that I would find the impressive edifice and music itself a satisfactory recompense for my troubles. And he might have been right, I suppose, had I at least been allowed to authentically enjoy the performance going on inside that hall as I might spontaneously appreciate any other cultural pursuit like a movie or a dance or a hip-hop concert -- if I could clap when clapping felt needed, laugh when it was funny, shout when I couldn't contain the joy building up inside myself. What would that have been like?

But this was classical music. And there are a great many "clap here, not there" cloak-and-dagger protocols to abide by. I found myself a bit preoccupied -- as I believe are many classical concert goers -- by the imposing restrictions of ritual behavior on offer: all the shushing and silence and stony faced non-expression of the audience around me, presumably enraptured, certainly deferential, possibly catatonic; a thousand dead looking eyes, flickering silently in the darkness, as if a star field were about to be swallowed by a black hole.

I don't think classical music was intended to be listened to in this way. And I don't think it honors the art form for us to maintain such a cadaverous body of rules.

The Way We Were

Joseph Horowitz in his wonderful new book, Moral Fire, describes audiences "screaming" and "standing on chairs" during classical concerts in the 1890s. The New York Times records an audience that "wept and shouted, strung banners across the orchestra pit over the heads of the audience and flapped unrestrainedly" when listening to their favorite opera singer at the Met in the 1920s. And Greg Sandow provides a brilliant analysis of classical music's average audience age over time, showing the form to have remained most popular amongst energetic thirty-somethings rather than subdued grey-hairs all the way until the late 1960s era of Mad Men.

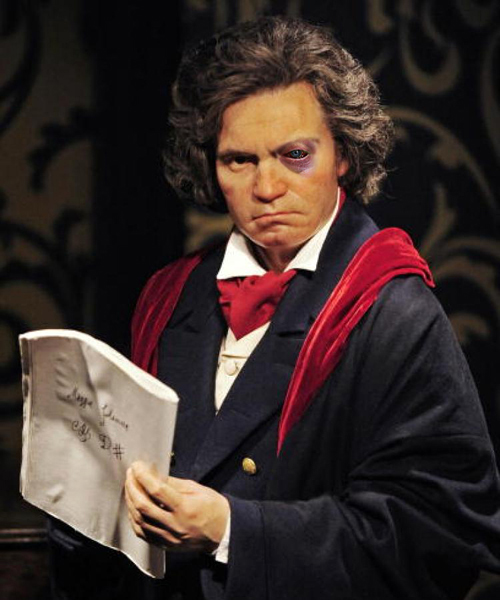

Indeed, even the venerable Beethoven, I am quite certain, would be dismayed to find his music performed the way it is today. Not to applaud between his movements? Unthinkable! Not to call out during the performance and react to the music he'd written? Preposterous!

To begin with, like many living composers, Beethoven was not universally understood or even particularly well liked -- nor did he care to be. Of his Third Symphony, the Eroica, critics who attended the 1805 premier wrote, "If Beethoven continues on this path, both he and the public will come off badly. Music could quickly come to such a point that everyone will leave the concert hall with only unpleasant feelings of exhaustion."

To his contemporaries, the sheer primal suspense in the Third was deliberately jacked up to such an unbearable degree that by measure 394 the first horn famously goes berserk, acting out the listener's agony of expectation by breaking in on the violins prematurely. So unprecedented and unruly was this bold psychological stroke that it was at first mistaken, even by the composer's close friends, for a sort of prank. His pupil Ferdinand Ries, thinking a blunder had been made, cried out, "Can't the damned horn player count?!" for which he came pretty close to receiving a sharp box on the ear.

Beethoven, it turns out, was not a follower of tradition. And no one was expected to keep quiet during his performances either. The music was much too wild, too complex, too dramatic and demanding. If it was gauche, the audience complained or praised at will just as they do today in non-classical concert experiences.

Nowadays, however, Beethoven it seems in spite of all his revolutionary fervor has along with the whole kit-and-caboodle of classical music become something of a rather dull commodity -- so perfect in every way that his music displays not really greatness or excitement anymore, but (I am sad to report) only "packaged greatness." Smugness, dullness, an over abundance of ritualism ... everything, in fact, that Beethoven hated.

What Can We Do Now?

One step therefore we might take to make classical music less boring again is simply for audiences to quit being so blasted reverential.

The most common practices in classical musical venues today represent a contrite response to a totalitarian belief system no one in America buys into anymore. To participate obediently is to act as a slave. It is counter to our culture. And it is not, I am certain, what composers would have wanted: A musical North Korea. Who but a bondservant would desire such a ghastly fate? Quickly now: Rise to your feet and applaud. The Dear Leader is coming on stage to conduct. He will guide us, ever so worshipfully through the necrocracy of composers we are obliged to forever adore.

The living composers I know though are real people. They bleed just like the rest of us -- or more accurately stated, because they are artists willing to put their thoughts into action for our review and criticism, they bleed publicly for us. They drink beers and feel tired and ride subways and dream about a better life. They are human and they want us to share a deeper, richer human experience together with them. They want, in effect, the same things Beethoven wanted.

Here are the two most shattering facts about classical music today: First, Americans are writing, playing, recording and listening to more orchestra music today than they ever have before in history -- mostly in the form of film music and video game soundtracks. So we know they like the general sound.

They just don't like listening to it with us, at concert halls. And that is the second fact.

Perhaps it's because of trying to keep classical music audiences living in the dark, in perpetual fear that they might not understand the secret and elite codes of long-term insiders, brainwashing core subscribers into an irrational hatred of anyone who dares to disrupt their peace-and-quiet even if accidentally, regimenting the experience with a coerced and inculcated rigidity that would be abhorrent to any composer worth his or her salt: This is how we have made classical music so awful.

Perhaps it's time to tell our own darling leaders to bug off and in place of their formalities simply allow ourselves to react to classical music with our hearts just as we do when we meet other forms of art. Classical music belongs to the audience -- to its listeners, not the critics, to the citizens, not the snobs.

Why not reclaim your music today?

What do you think, readers? Do you think classical music could be presented in a better way than it is today? Let us know your thoughts in the comments.