Before the blizzard hit New York, I had my own watershed moment: Christmas with Shoah.

Claude Lanzmann's nine-hour epic returned to the big screen on its 25th anniversary. It opened in uptown Manhattan, at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas, on Dec. 10, and landed at the IFC Center in New York's Greenwich Village on Christmas Eve as part of a national re-release. I took it as a sign, or rather, an invitation.

My folks were out of town and the Jewish museums were closed (Christmas fell on Saturday, the Sabbath). My Christmas companions of years past were busy with spouses and boyfriends. I was back from a trip to Poland that included a day at Auschwitz-Birkenau. It made sense to continue the exploration, to find other people with a similar focus. At least that's what I told myself.

The Night Before

On Christmas Eve, I told friends about my plans. They winced.

"Why don't you come over afterward for some hot chocolate and key lime pie?"

I liked the idea of having someone to share the aftermath, especially since I had my own misgivings about seeing the movie. Was this an extreme form of self-flagellation, a special Christmas-issue dose of masochism?

Nonetheless, a nine-hour movie solved the problem of what to do on Christmas Day -- and night. And could help ward off the particular brand of self-pity that can come with being alone on Dec. 25. Even for a non-celebrant.

"It's a good place to find Jews on Christmas," I told the key lime pie friends.

"What about a synagogue," they asked, "aren't there Jews there?"

I wanted a different kind of prayer. Plus, it was tradition.

As a kid in Hebrew school, I made a lavish book report cover that represented Elie Wiesel's Night with a flame-laden sky and barbed wire made of black thread studded with unruly knots.

One Saturday night in college I went to a film about Janusz Korczak, the Polish-Jewish doctor, educator and head of an orphanage who accompanied his charges to their deaths. My peers went to concerts; I schooled myself in death marches, hidden children, kinder transports and lives of shtetl dwellers.

The Screening

I packed vegetable dumplings, fresh-made biscuits, a container of salmon and broccoli rabe and a thermos of black tea with milk. "It's going to be a rollicking show," I joked to the woman in front of me at the IFC Center box office, relieved to discover another Shoah traveler.

"What else am I going to do on Christmas?" she shrugged.

The theater was small and packed, more than 50 people in tall-backed seats. I migrated to the front row and stole glances at the audience: a trio of female college students, white-haired couples, a pair of Japanese tourists, middle-aged guys in sweatshirts, artsy-looking 20-something dudes who pooled golden chocolate wrappers in the cup holder between their seats. The woman a few seats over crunched popcorn and slurped soda. It was her second time, she told me during the first intermission. During a pan of the verdant killing fields at Chelmno, an elderly man came in, sat down and took his coat off. An hour later he put it on and left the theater.

Mantle of Memory

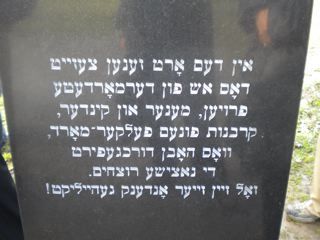

Last month in Birkenau, I lingered in front of the pond of ashes where four stones are engraved in Polish, Hebrew, Yiddish and English: "To the memory of the men, women and children who fell victim to the Nazi genocide. Here lie their ashes. May their souls rest in peace."

I swallowed rage, sorrow, nausea and hoisted the biggest stone I could find onto the Yiddish marker, proof of my presence. Shoah required a different kind of lifting. I kept running commentary on what had changed since Lanzmann turned his camera on the extermination camp: no weed along the tracks, markers in front the ash pit, a thicket of tour buses.

When the screen filled with the steps to Crematorium II, my shoulders folded, my eyes closed and I gagged slightly. The popcorn cruncher had left. I was alone in the first row.

The final credits rolled at 11:45 p.m. Two dozen of us Shoah watchers gathered our things, nodded toward each other and moseyed to the lobby. One man joked about the end of "Shoahfest," another talked of his drive back to Princeton, N.J. We congratulated each other on our endurance.

Too late for key lime pie.

The Chaser

The 20-something chocolate wrapper guys recruited a lanky, blond French Ph.D. student for a drink and invited me to join.

Just before midnight, four of us perched on low stools in the back room of a Bleecker Street bar. We distilled the close-ups and wide shots over Christmas cookies and pints of Guinness. They explained the technology that allowed Lanzmann to capture clandestine video of the former SS men he got on tape. We wondered which of the interviewees might still be alive.

Most are not.

Shoah began with a line from the Old Testament: "I shall give them an everlasting name" (Isaiah 56:5).

Three gentiles from Tennessee, Miami and Le Havre, France, and a Jewish gal from Brooklyn had dedicated a day to it. At 2:30 a.m. we exchanged e-mail addresses and parted ways.

For the first time, I felt fellowship on Christmas. The day was holy.