This is the first in a series on visual artists who have embraced, redefined and subverted the computer-generated imaging (CGI) and 3D-simulation modeling originally developed to compose special effects graphics and animation in mainstream film, video, gaming, and high end advertising. See Part 2 of this series, Matthew Weinstein: When the Revolution Comes, It Will Be a 3D Animation Entertainment With Art Merchandizing; Part 3, And Some See God: Getting to the CORE in the 3D and Immersive Art of Kurt Hentschlaeger; and Part 4, PostPictures: A New Generation of Pictorial Structuralists is Introduced by New York's bitforms Gallery.

Claudia Hart has spent the last decade escaping Grand Theft Auto, RapeLay, Modern Warfare, Counter Life, Blood Rayne, Full Spectrum Warrior, Hitman, and all 3D rampaging, male-avatar rape and kill animation games crowding the human machine interface (HMI). As a rare woman artist using state-of-the-art 3D computer-generated imaging (CGI) software outside the entertainment, gaming, and advertising industries, Hart has to circumnavigate her share of gender obstacles to keeps apace with each new development in 3D media, particularly those in gaming. The barrage of simulated assault can be overwhelming as Hart finds herself regularly fending off testosterone-fueled, 3D fantasies depicting female avatars virtually overpowered, imprisoned, and gang raped not only by male sociopath avatars, but by the millions of gamers whom she sees as willingly participating and identifying with them.

It's small wonder that Hart's own art has manifested as a series of serenely utopian escapes from the violent misogyny of gaming and other special effects media. Literally, Hart constructs digital eScapes from meticulously-produced 3D animation videos with the same special effects software--Maya, Shake, Z-Brush, and Mental Ray--propelling Hollywood mega-studios DreamWorks and Pixar. Exhibited sometimes on conventional flat screens, they are more effectively projected onto whole walls so that viewers can experience their full pictorial impact. The enlarged scale also enables viewers to appreciate the work's embodiment of mythopoetic and structural models.

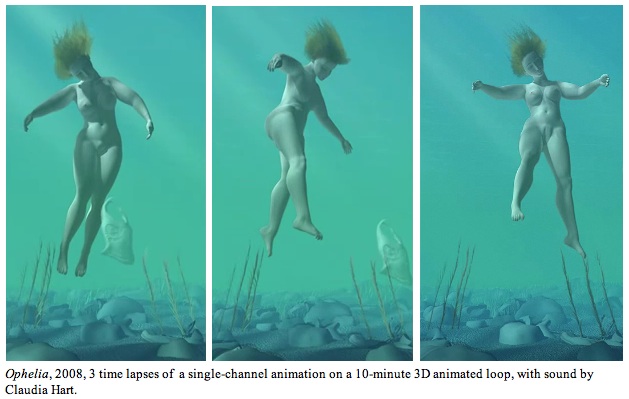

2-minute excerpt from Ophelia, 2008, single-channel animation on a 10-minute 3D animated loop, with sound by Claudia Hart.

In their mythopoetic functions, Hart's eScapes afford safe havens sheltered from the Clockwork Orange Syndrome--the fixation on adolescent hetero-male fantasies driving the entertainment, gaming, and advertising industries. Hart reacts to the mainstream productions she sees as a primary source for the formation of world views. Knowing that popular culture increasingly supersedes even the world views constructed by religion and science, Hart believes that the entertainment and gaming industries are producing more than warrior wet dream machines. Operating ritually and unconsciously in young minds on the level of belief-formation, video games and movies inform personal lifestyles, identities, and priorities profoundly affecting relationships and functioning in the world. When factoring in media imagery disparaging to women, misogyny becomes internalized not merely as a prejudice, but as a "desirable" fact of life.

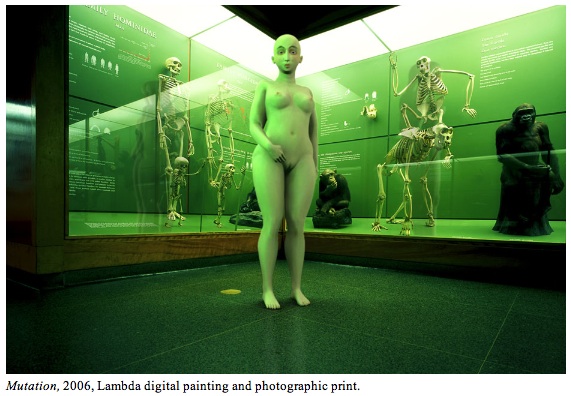

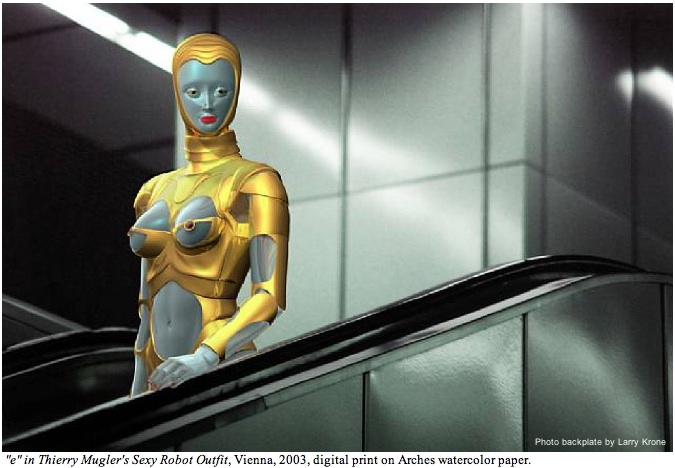

Structurally, Hart's eScapes assimilate her interests in animation, painting, sculpture, cinematography, audio art, and new media. Some of her earliest 3D-painted avatars were scanned into photographed settings and made into digital prints (such as Hart's "e" in Thierry Mugler's Sexy Robot Outfit and Mutation, seen here). But in the last few years, Hart's imagery has been composed entirely out of modeled and painted pixels without use of photography. And because they depict a single, fixed pictorial scene, not a succession of scenes, as do conventional video and film, they defy the animation genre she works within to emphasize a stillness and slow pacing that conveys little more information than a painting or photograph. What little motion they possess is more an organic unfolding or variation of what is established in the first nanosecond of the observed image, making all motion more an evolution of a scene than a scene in action. We watch a record of the painting's creation, minus sight of the painter. And as most of her recent works are comprised entirely of 3D modeled and painted figure-and-field relationships, the eScapes are best described as models of New Media Painting, or simulated painting.

2-minute excerpt from Dream, a single channel projection, 7 minutes-14second loop, with music by Edmund Campion, 2009.

Although Hart's eScapes are made with the use of computers and software algorithms in place of brushes and paint, the figurative modeling of avatars and their environments require the same visual aptitude for line, shading and light in the building up of illusionistic volumes, contours, surface colors and textures from pixels, as do the application and modeling of paint on a canvas. Which means that Hart's mastery of computer imaging is dependent on the same artistic hand-eye/eye-brain coordination that our ancestors developed in making cave paintings.

We are wise not to mistake Hart's female subjects as representations of women, real or fictional. In Hart's pictorial scheme they are automatons--legatees of Donna Haraway's "feminist cyborgs," the name Haraway gives to individuals who use technological advancement to channel their life force into objects that propel them beyond conventional gender constrictions. In like mind, Hart channels her life force not just into her female automatons, but into the environments they inhabit. If she retains the female biological form in each of these eScapes, it's because her experience of the media's devaluation of women requires a counteractive imagery that revitalizes her personal identity as a woman.

2-minute excerpt from Machina," a life-sized single-channel video installation on a 20 minute loop, 2006.

We see evidence of serenity regained in Machina, the first of Hart's animated avatar paintings. Besides disavowing the machismo of action avatars in cyberspace, Machina pokes fun at the fairy-tale protagonists of Snow White and Sleeping Beauty instructing children on the ideal and prescribed behaviors for the female gender. But Hart's nude, sleeping odalisque requires no prince to wake and satisfy her. Machina may be alone, but she is visibly enrapt with her self-contentment, which we read from her body's slight, rhythmic breathing and facial expressions. Despite her obvious caricature, the scene's pacific nature rivets us to Machina's slightest movements, and we wait through the long intervals of her repose, during which she offers little or no motion, just to catch sight of the periodic turning and twisting of Machina's head and torso; her hand rubbing somnambulistically against her pelvis and pubis; or the unexpected opening of her eyes. But the real novelty lies in her serenity and stillness, the effects by which Machina ironically represents human qualities that the mainstream media, and specifically the industry of cinematic visual effects, ignores--the qualities of integrity, subjectivity, and quietude. Machina captivates for paradoxically being an allegory of banality.

After watching the loops cycle more than once, it becomes evident that Hart's automatons and eScapes resemble clockworks, and as clockworks their every mannerism and quirk is programmed to the nanosecond. If this resemblance serves some purpose, it's likely to analogize our fascination as viewers with 3D imaging to the fascination our ancestors held for clockworks in the 17th through 19th centuries. It's no coincidence this also happens to be the great age of European Painting, as Hart's analogy underscores the lineage of her 3D automatons to the painted female subjects of Correggio, Rubens, Fragonard, Goya, Delacroix, David and Ingres.

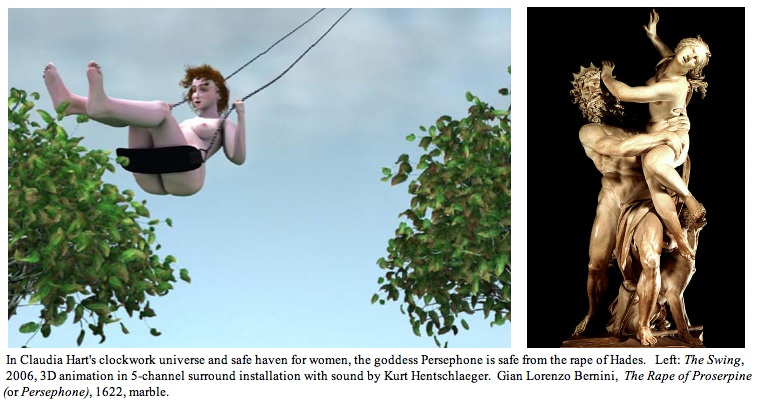

3-minute excerpt from The Swing, 2006, the 3-channel version of a 3D animation with sound by Kurt Hentschlaeger.

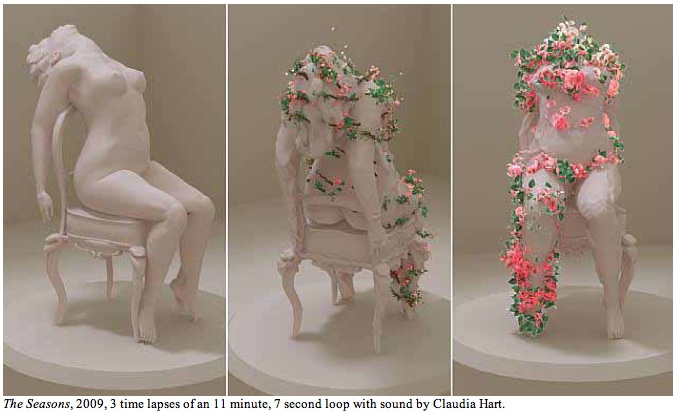

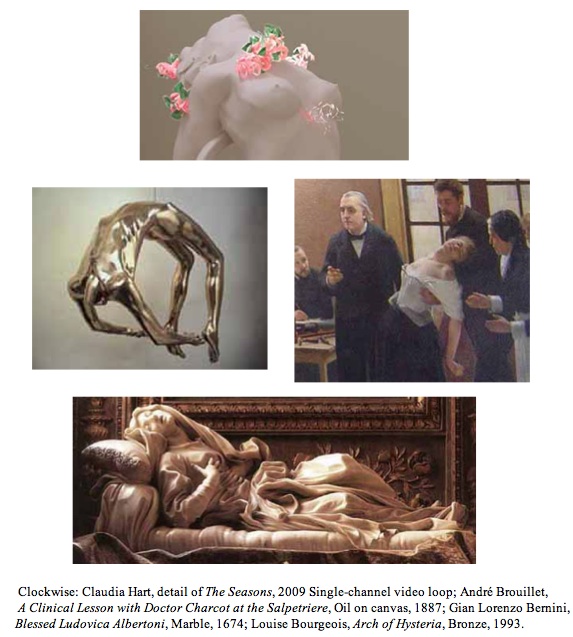

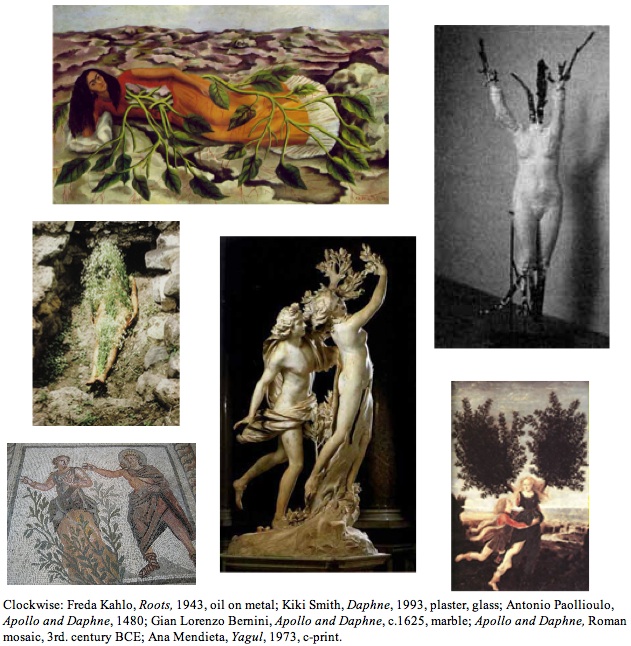

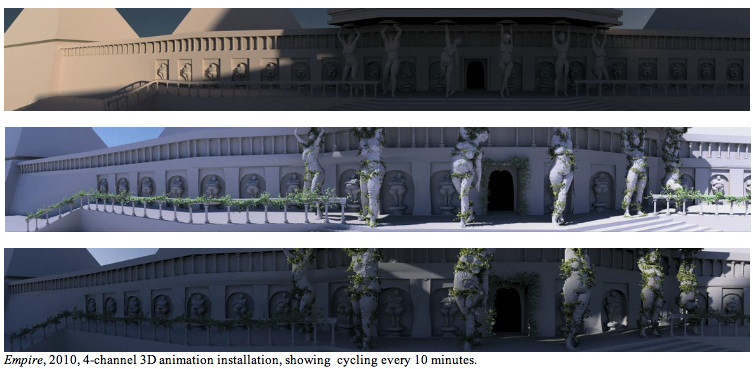

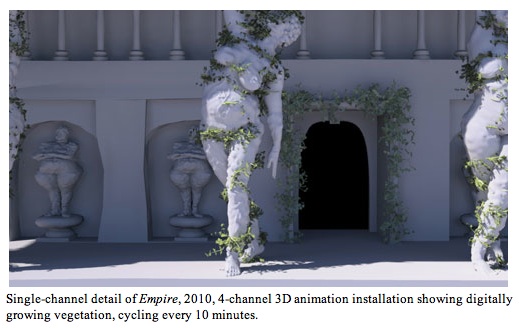

As with clockworks, we see in Hart's eScapes references to historical myths in a baroque, whimsical and suprahuman iconography--the swing from the sky in The Swing; sculptures sprouting organic growth in The Seasons and Empire; a body breathing underwater in Ophelia. As mythopoetic domains, Hart's clockwork eScapes reprise age-old myths and legends of rape and abuse--Persephone abducted by Hades; Daphne stalked and manhandled by Apollo; Ophelia emotionally tortured and suffering the murder of her father by Hamlet. Except that we find the eternal plights of the myths intervened on by Hart to effect their revitalization and restoration for women today. It is particularly instructive that Hart reclaims not myths of amazon combat, but myths that respond to violence with the transformation of traumatic yet epiphanic awakening.

Without intending any diminishment on Hart's work, I personally can't help seeing in the combined motifs of escape, automation, and especially Hart's states of sustained innocence, the kind of purposeful fracturing that occurs in Dissociative Personality (or Multiple Personality) Disorder. It's exactly the kind of sexual, physical, and emotional abuses that Hart indicts in the misogynistic representations of popular culture and ancient myths that are widely considered to compel children at an early age to retreat from reality into multiple personalities not unlike the havens of escape Hart has engineered.

5-minute 18-second excerpt from The Seasons, 2009, 11-minute loop with sound by Claudia Hart.

In the Greek myth of the goddess Persephone, time is fractured into four seasons with Persephone's rape by the god Hades. But in The Swing, Hart's Persephone-automaton is freed of Hades to enjoy perpetual play through the unfolding years, during which the seasons pass as if minutes. Although clearly an adult, The Swing's automaton displays a prepubescent pubis, signifying she represents the desire for sustained innocence.

In The Seasons, a stark white sculptural automaton that seems to be Nature herself is seen swooning over a chair as she slowly metamorphoses into a plant. It's an image reminiscent of Ovid's Daphne, who is spared the rape of Apollo by the intervention of the goddess Artemis. With Hart stepping in for Artemis, the automaton Daphne is now, in her perpetual video loop, made as timeless and self-sufficient as any god possessed of the life-giving and life-ending propensity for organic growth and decay. Its a symbology that makes Hart's automatons oppositional to Cartesian anxiety and the Freudian ego ideal, but attractive to artists from Roman times up to the modern era--I think here particularly of work by Frida Kahlo, Ana Mendieta, and Kiki Smith.

No longer faced with fleeing Apollo's lascivious embrace, Hart's Daphne gives her body over to a relaxed abandon that resembles the "arch of hysteria," that tragic misdiagnosis of Jean-Martin Charcot. Thought by the 19th-century physician and theorist to be a mysterious disorder of the feminine disposition, we know today that hysteria is a complex of behaviors aroused more likely as an unconscious revolt of the human psyche--male or female--to sexual repression and deprivation. In The Seasons, Hart's automaton simultaneously elicits the convulsive posture of hysteria while converting its psychic energy into an unapologetic display of eroticism that only Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Louise Bourgeois have sublimated with more histrionic effect.

Despite the automaton's passive state, The Seasons' equation of nature with sexuality may be a combative act after all, in that it counters the religious and clinical de-sexualization of women at the same time it confronts the modern pornographic fixation on her depersonalized shell. By sprouting a full body bouquet, Hart's Daphne-like automaton seems to shield her body from our gaping while turning the empowering CGI universe to her benefit through a metamorphosis that simultaneously invites comparison with the cinematic adaptations of comic book superheroes and mutants.

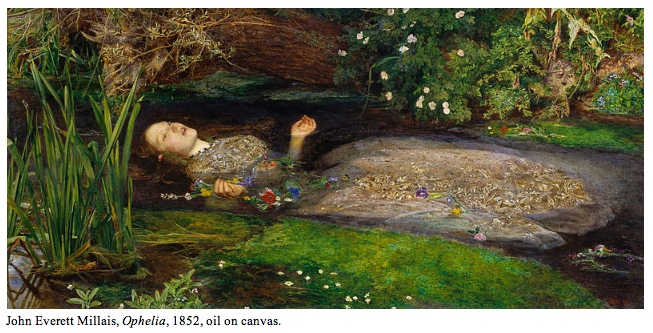

In a similar rescue of myth, Ophelia's immersion into water is no longer the act of despair Shakespeare made it out to be, as Hart's Ophelia comes into her element only after she descends beneath the water's placid surface. As a Medieval woman in Shakespeare's Denmark, Ophelia has been reduced to a romantic figure of chivalry, but one without a romance. Shakespeare shows us what happens when a woman defined and evaluated by men is then deprived by men of the role by which she is defined and valued. Hart, in turn, seizes on Ophelia's depression and suicide by drowning, converting both into her automaton's baptism in the ocean of rebirth and enlightenment. Unlike John Everett Millais' famous rendition, Hart's Ophelia is not depressed and dying, but delighting in the oceanic motions symbolic of an unconscious in sync with nature.

By now it must be clear that Hart's employment of CGI effects, though retaining the cinematic property of motion, requires skills akin more to traditional modes of drawing and painting than to photography and cinematography. And yet many 3D animators have been negating their own talents, as well as diminishing the status of computer-generated painting, by referring to the computer as "a virtual camera" rather than acknowledging it as a painting tool conveying the contents of the mind. Viewers at least make an uninformed assumption that when they watch an image that is projected or onscreen, especially an image that moves, they are watching an image shot with a camera, perhaps in the fashion of analog, frame-by-frame animation. But when CGI artists do so, it's often because they are seduced by the associaton with cinema. In both cases referring to the computer-generated process of non-photographic imaging reinforces an illusion that is no more real than was the illusion of "the window onto the world" used by Renaissance painters to analogize the naturalism of perspective painting.

4-minute excerpt from Empire, 2010, a 4-channel 3D animation installation, cycling every 10 minutes.

Hart playfully acknowledges both these analogies simultaneously in Noh-timeGarden, whereby she simulates the virtual motion of a forward-tracking camera (which is really no more than a painted animation) and plays it off the Renaissance window of perspective painting (also painted), then bifurcates the experience of "passing through" two simulated windows. Hart's double simulation calls attention to the extent to which the perception of the picture in modern civilization has been so thoroughly redefined by photography and the cinematic experience that we willingly respond and refer to 3D imagery, like that of Hart's, as though it depicts the motion of a camera instead of an animated painting.

2-minute 31-second excerpt from Noh-timeGarden, 2007, a 2-channel 3D animation screen-based installation, with each screen cycling every 7 minutes, 30 seconds. Custom audio software and sound design by Hans-Christoph Steiner, vocals by Claudia Hart.

It's a prejudice that signals many of us are largely unaware that the pinnacle of artistry has, with the use of the computer and virtual effects software, turned a full 360 degrees in shifting, first from hand-eye coordination in painting, then to automatic reproduction in photography and film, and now back to the hand-eye coordination of 3D computer animation and virtual effects. Whether or not this means that CGI and 3D animation will become the dominant future mode of painting is to be contended. But Hart's 3D projected paintings suggest that were Goya, Rubens, Delacroix and Ingres alive today, CGI would be their medium of choice.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.