On a bright, unseasonably hot morning in early May, Susan Meredith pushed her kayak off the banks of the Little Blackwater River, a shallow, 15-mile tributary running through Dorchester County, on Maryland's Eastern Shore. The water, cool and dark, is almost perfectly still, broken only by the occasional leaping fish.

Today, the quiet marshes provide refuge for wildlife -- ospreys, bald eagles, muskrats, the endangered Delmarva fox squirrel. But 160 years ago, it was people who sought refuge in these marshes, using the water, grasses, and trees as they fled slavery. Harriet Tubman, herself born into slavery in Dorchester County in the early 1820s, led dozens of African-Americans through this region to freedom in the North as part of the Underground Railroad.

The region remains largely unchanged from Tubman's time, save the paved roads, a few buildings and a distant cell phone tower. Tubman's grandmother, Modesty, lived on a farm across the street from where Meredith launched her kayak. "What you're looking at is what she looked at," said Meredith, owner, along with her husband, of Blackwater Paddle and Pedal. "What you're seeing, she saw."

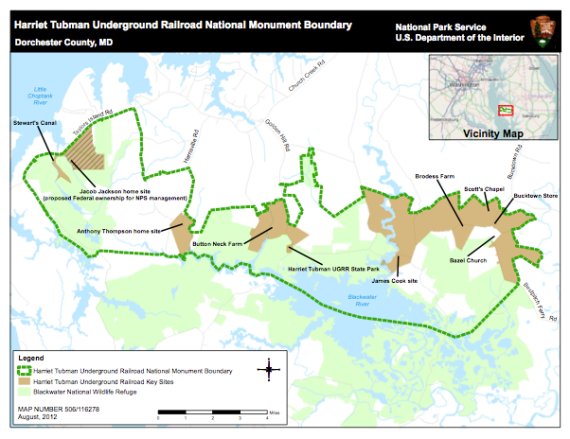

In March 2013, President Barack Obama granted new protections for 11,750 acres here, with an executive order designating this as the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument. The state of Maryland is building a new visitor center not far away, where people will be able to learn about this chapter of American history.

But sea level rise fueled by climate change threatens this flat, low-lying peninsula. The Tubman site, though one of the newest in the national park system, is also among those most at risk from climate change impacts. It's included in a report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, released Tuesday, that details risks posed by climate change to 30 cultural and historic landmarks across the country.

The sites include the Cesar Chavez National Monument, in California's San Joaquin Valley, where the famed Latino labor leader led the United Farm Workers. Record droughts imperil the future of agriculture in that area. In southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, climate-fueled wildfires are threatening ancestral Pueblo sites, in places like Mesa Verde National Park and Bandelier National Monument.

All along the East Coast, sites like Tubman are imperiled by rising seas and storm surges. That includes the oldest city in the country, Florida's St. Augustine, which the Spanish settled in 1565. It also includes Jamestown, Virginia. the site of the first permanent English settlement in the U.S., which dates back to 1607.

The reason the report highlights these locations, which include both national and state parks, as well as other cultural and historic sites, is simple, said Adam Markham, director of the Climate Impacts Initiative at Union of Concerned Scientists: "People care." Regardless of party affiliation, region, or background, parks and historic sites resonate with Americans -- and you don’t have to look any further than last year's government shutdown for evidence of that. At the same time, said Markham, "these are places that people probably will never have associated with climate change."

In Maryland's Dorchester County, Tubman's history dots the landscape. A signpost notes the location of the Brodess farm, where she was born Araminta Ross around 1822. Her first known act of defiance against slavery took place not far from there, at a small general store in Bucktown. As the story is retold in the 2004 biography Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom, she sought to protect a fellow slave from an overseer, who threw a lead counter weight that struck her in the head, causing a wound that was "deep and severe."

She took the surname Tubman when she married John Tubman, a local free black man, in 1844. She took the first name of her mother, "Harriet," when she escaped slavery at age 27. But Tubman's story in the region didn't end there. She came back repeatedly to free family members, including a niece and two brothers.

"It was the love of her family that brought her here," said Meredith as we paddle the river, looking out at marshes that Tubman might have used to her advantage as she eluded her would-be captors. "She knew this place like the back of her hand."

Historians estimate Tubman returned to the region around 13 times, and helped at least 70 others escape to freedom (some accounts say it was as many as 300). It was the rich history of the landscape, still largely untouched, that the monument designation seeks to protect.

"There hasn't been a lot of development in that area, so it probably looks as she would have remembered it," said Cherie Butler, superintendent of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument. "It's important that we preserve it. Her story is important, and we want visitors to be able to experience that area as Harriet would have experienced it."

For the National Park Service, climate change "is very much something we're thinking about," said Daniel Odess, chief scientist for cultural resources at the park service. "We have a lot of assets in harm's way."

The park service doesn't have an estimate of how much climate impacts might cost, said Odess, but there are a lot of areas of concern. That includes looking at museum facilities in flood plains that might need to be relocated, historic buildings that might need to be made more resilient to storms, or changes in things like mold, fungus, or termites—all of which could affect historic structures.

"We're really just starting to recognize the whole range of kinds of effects that are occurring," said Odess. At the same time, the National Park Service is already facing an $11 billion backlog in basic maintenance -- and that's without including climate-related costs in the future. "One of the challenges we're confronted with, in these austere budget times, is how do we set priorities? Where do we put our effort? Who gets to decide?" said Odess.

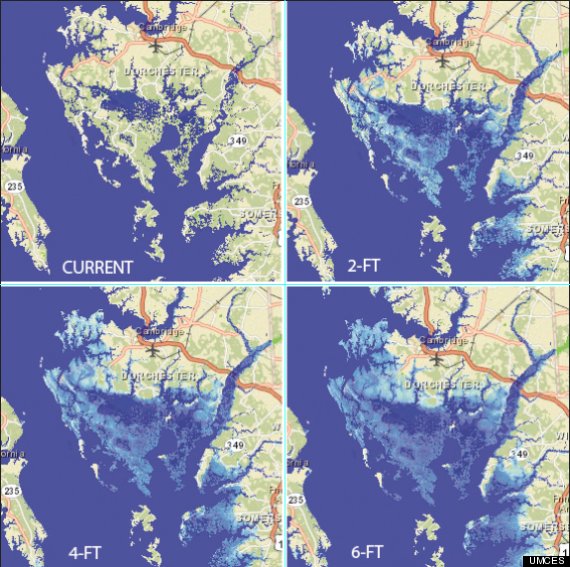

Because it is so new, planners working on the Tubman site are well aware of the risks of climate change. In this region, the land has long been slowly subsiding due to glacial retreat. But climate change, which causes thermal expansion of the oceans and the melting of glaciers, is making the seas rise much faster than ever. By 2050, the area can expect about 2 feet of sea level rise, according to a report the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science last year. By 2100, scientists anticipate sea level will rise 3.7 feet to 5.7 feet.

Sea level already has risen by one foot in the 20th century, said Donald Boesch, president of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science and chair of the group that assembled the sea level rise report. That is much faster than in the 19th century, when sea levels were relatively stable. "It is a quite dramatic change in really a short period of time in human history," Boesch said. "If you put it in the context of what it was like when Harriet Tubman was alive, it is something that is really unprecedented."

The implications here are severe. "Even the areas that aren't wetlands are not very high above sea level," said Boesch. "A small amount of sea level rise would result in a large amount of inundation, because the land is so flat."

The Tubman site includes areas owned by the National Park Service. A portion is part of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge and managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and another piece is owned by the state. The state is in charge of the visitor's center, and earlier this month announced a $13.9 million contract to begin construction. Officials said they expect it to be completed in early 2016.

Jordan Loran, director of engineering and construction for the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, said the visitor center location will be built outside of the 50-year floodplain. And the base of the center will be constructed two feet above the 100-year floodplain, to make it even safer. "Obviously that area it is a low area, but because of the historical significance of the landscape, and being close to the story of Harriet Tubman, we needed to be in that area," said Loran.

Advocates had fought to get the landscape protected for years, said Alan Spears, government affairs cultural resources director at the National Parks Conservation Association. "It was a decades-long effort to honor Harriet Tubman," said Spears. "So the idea that in 40 years much of that could be underwater is a pretty reprehensible notion."

Of course, there are best-case and worse-case scenarios for future sea level rise, largely based on whether the world's nations take meaningful action to curb climate-changing emissions. Whether we're on the high end of the projected rise by 2100 or the low end remains to be seen -– and that could make all the difference for a site like the Tubman monument.

"We're hoping people don’t have to rent scuba gear to enjoy the resource," said Spears.