photo © Patrick Varotto

Clichés abound about the impossibility of making surrealist art in a 21st century world where nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles are called peacekeepers and chickens held in two-foot square cages are labeled free range. That said, where better to fly this winter than to France, the land of liberté, fraternité, bureaucracy to look at and reflect upon history's greatest Surrealist icons: Jean Cocteau (who denied being one) and Salvador Dali (who marketed his Surrealist images and profiles in a vast fortune, then broke with them).

The Dali show is at the world's pre-eminent modern art museum, the Centre Pompidou in Paris -- while a new set of Cocteau's artistic remains are entering their second year exposition at the magnificent Cocteau Museum at Menton on the Côte d'Azur in southern France. Far more impressive than this year's show of the drawings, paintings, sketches, doodles and the films that make up the Severin Wunderman Cocteau collection is the museum designed by Rudy Riccioti.

From overhead the museum seems to be a great triangular pavilion mounted on drunken columns. Closer, at ground level, in the early twilight the columns become an array of seductive arms that beckon you in. (Riccioti, surely Italy's most dazzling architectural star, is also the key designer of the cultural complex opening this winter in Marseille as that city of bouillabaisse and gangsters takes on the mantle of European Cultural Capital 2013). Riccioti's building alone is worth the ticket from Paris.

photo © Patrick Varotto

But then there's the Cocteau work. His idolaters praise him as one of the great polymaths of the 20th century, a courageous avatar who maneuvered his way through both the excitement and glitter of les années folles, never hid his homosexuality (even while promoting his efforts a dalliance with exiled princesses), and challenged conventional surface realities. All of which is, to a degree, true. Cocteau, who preferred to be known as "the poet" for both his verse and his plays, was friends -- or at least in the circle of: Gide, Appolinaire, Modigliani, Picasso, Nijinsky (whom either bedded or wanted to), and Stravinsky, not to mention the 15-year-old boy poet Raymond Radiguet who was his first great passion.

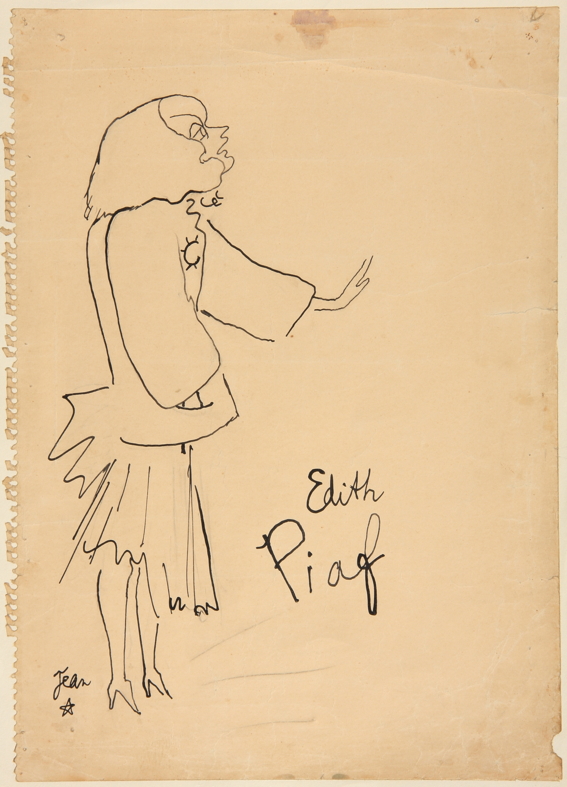

The first grouping of the Wunderman collection opened in late 2011; it was probably his best work. This second year's could have been more interesting. It aims to be a didactic rendering of Cocteau's obsessions, notably his "sacred monsters" -- from his worship of the great Sarah Bernhardt to his Freudian-lite dreamscapes to his adoration of Edith Piaff, the little squirrel who "regretted nothing" and warbled worldwide of her vie en rose. Like the theatrically tragic Judy Garland, Piaff was every gay lad's big sister for whom violence and tragedy were lifelong branding irons. The easy-kitsch explanation of Cocteau's departure from life on the same day as Piaff's death on October 11, 1963, has long been that once he learned of her death, he could not continue.

While that's an unlikely medical explanation, it fits the story and in some ways captures what's good and not about Cocteau and the Wunderman collection. Take, for example, the clips from his best film, La Belle et La Bête, a melodramatic rendering of Beauty and the Beast, in which the daughter enters the beast's garden to plead for her father's life (whom the Beast had condemned to death for stealing a rose). Naturally the daughter and the beast fall hopelessly in love. "Belle! Belle!" and "Bête! Bête!" they cry to each other in the dark.

Well. It might have been better left as a children's fantasy even if the film is visually stunning.

But of course there are subtexts, no less with the would-be Proustian Cocteau than with the hyperventilating fantasy daughter. The actor beneath La Bête's furry costume was of course the great beast of Cocteau's life, Jean Marais, the super-hunk of limited talent with whom he slept (to make an obvious euphemism) for the last quarter century of his life. Their relationship was an open secret in France -- more open even than Rock Hudson and Marc Christian. Yet nowhere in the current Wunderman show or in the guided interpretation is there any psychological or sexual depth to the array of queenly pieces on display meant to open up Cocteau's inner life. Marais is presented simply as "his friend."

Jean Marais, Cocteau's great love as Oedipus in "La Machine Infernale"

Nor is there even the slightest tinge of irony in the blurbs and captions presented a few steps away in Menton's public marriage chapel. (Yes, in officially "laic" France, most town halls have marriage chapels.) Cocteau spent two years -- 1957 and 1958 -- decorating the vaulted marriage chapel with frescoes of... a very pretty garden of delights. But you would have to be terribly myopic to imagine the hall dedicated to heterosexual romance: sturdy, naked, hyper-phallic young lads frolic above and around the wedding parties, warning of bestial Greek tragedy if the newlyweds -- presumably represented by a young lady and a fisherman at the back of the hall -- do not tend each other with care.

On the other hand, assuming the current government passes its promised extension of marriage to same-sex couples, the Menton marriage hall might well become the destination of preference for lads looking for matrimony.

There is, of course, the other untidy darkness in the Cocteau story. That is his close "friendship" with Adolph Hitler's personally anointed sculptor Arno Breker. Just how close Breker and Cocteau two were has never been determined, but Cocteau certainly went out of his way to praise Breker during the French occupation and Breker, who was not without talent, crafted what is surely the best if fanciful stone head yet made of Cocteau. But then Cocteau also defended Hitler as a gentle pacifist just before the war's outbreak; Cocteau was investigated for collaboration with the Germans after the war, but finally, unlike his close friend Coco Chanel, he was not prosecuted (while she, as a cosmetics icon, was forgiven).

Perhaps it's nothing but caviling to recall the unexamined details in the Cocteau mythology. He is hardly alone among the world's famous artists for carrying his shadows, yet for a self-identified prober and interpreter of the inner spirit as the motor of artistic expression, there is much that seems absent in this year's exhibition from the Wunderman Collection and it cries out for supplements perhaps beyond those that the late Mr. Wunderman -- himself a refugee from the Nazis -- kept in his vaults.