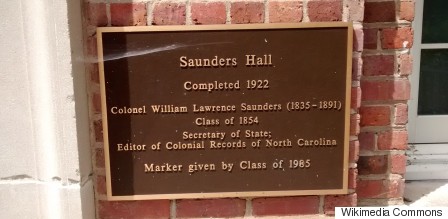

Two weeks ago, the board of trustees of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced that Saunders Hall -- named for William Saunders, a 19th-century North Carolina secretary of state and chief Ku Klux Klan organizer -- would be renamed Carolina Hall.

This wasn’t enough for many activists who have been fighting to remove Saunders’ name. The same day, the board also announced a 16-year freeze on naming other buildings -- meaning that Aycock Residence Hall, named for white supremacist and former North Carolina Governor Charles Aycock, will remain as it is until at least 2031.

Aycock Residence is just one of many college buildings named for American historical figures who were known to have an active role in perpetuating systemic racism. At some schools, students, professors and community members have been fighting to remove these names, in some cases coming up against strong administrative opposition. At other schools, the names remain uncontested.

A Huffington Post general survey of buildings at the University of Mississippi, University of Alabama and University of South Carolina found 10 buildings named after unambiguously racist historical figures. Often, these people were notable politicians -- and some, like former Alabama Governor Bibb Graves, did help improve certain aspects of their states -- but they also actively worked to oppress and disenfranchise black people, or else benefited directly from racial injustice.

At two South Carolina schools, Clemson University and Winthrop University, activists have called for their respective Tillman Halls to be renamed. Michael Fortune, a retired lawyer who recently moved to South Carolina and took courses at Winthrop, was unaware of the building’s namesake until he saw a history show on TV that happened to discuss Benjamin Ryan Tillman, a governor and senator of the state at the turn of the 20th century and an outspoken racist.

"A young black student walking by Tillman Hall -- if he knew what that stood for, he’d be sick, because [Tillman] thought no black man will ever lead us,” Fortune told HuffPost. “And yet in their brochures they say 'Come to Winthrop and learn to be a leader.'"

Last fall, Fortune, along with another former Winthrop student, began pushing for the school to rename the building. They spoke at a board of trustees meeting in October but were later told that the school couldn't change the name due to a state law, according to The Herald, a South Carolina newspaper.

The law referred to is South Carolina’s Heritage Act, a piece of legislation passed in 2000 that says that streets, parks and other public areas named for historical figures may not be renamed without a two-thirds vote from the state General Assembly. The law also applies to certain memorials and monuments. In a statement to HuffPost, Jeff Perez, senior counsel to the president for public affairs at Winthrop, mentioned the law, noting that a supermajority vote to change the name of Tillman Hall is “an outcome even the most ardent supporters of renaming recognize is not likely.”

This explanation has also come up with regard to Clemson. State Sen. Larry Martin (R) told WSPA in February that it was possible someone in the state legislature was actively working to rename Clemson's Tillman Hall -- but, he added, "I don't know of it, I haven't heard of it, nor do I anticipate it." Martin did not respond to a HuffPost request for comment.

The Clemson faculty passed a resolution earlier this year recommending that the administration consider changing the name of Tillman Hall. Students also campaigned for a name change. Board of trustees chairman David H. Wilkins issued a statement in February saying that the school has no intention of changing the names of any of its buildings. Rather, wrote Wilkins, "we believe that other, more meaningful, initiatives should be implemented that will have more of an impact on the diversity of our campus than this symbolic gesture." In December, Clemson President James Clements had spoken about the need to address diversity and racial insensitivity at the school.

The idea of “more meaningful initiatives” was also brought up at UNC in the debate about Saunders Hall. Activists there had campaigned for the building to be renamed after the acclaimed black author Zora Neale Hurston. Last week, The Daily Tar Heel, a UNC student newspaper, reported that advocates for changing the name of Saunders Hall are disappointed with the new name, Carolina Hall.

“[The board] wanted to talk about how we as activists could be doing something better with our time or doing work that’s more meaningful or how we should be working towards unifying our university,” rising senior Ishmael Bishop told HuffPost. “They used it as a stunt, as a way of quieting student voices.”

At Clemson, the faculty now plans to work in other ways to create a more welcoming campus climate.

“We recognize that the board has this decision authority and we certainly respect and will abide by their decisions,” said Jim McCubbin, a professor of psychology and president of the faculty senate at Clemson. “We may not necessarily agree with them, but we certainly respect their authority.”

Orville Vernon Burton, a professor of history, sociology and computer science at Clemson, believes that renaming the building would be much more than just a symbolic gesture. People tend to get their history from monuments, he told HuffPost, and to name things after certain historical figures is tantamount to promoting their work, and only their work, as something worthy of recognition.

Burton, who has written several books about Southern history, said that South Carolina has two historical narratives -- the one in which it started the Civil War, and the one in which it was the site of the first case in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case that integrated U.S. schools.

“There are two major traditions in South Carolina,” Burton said, “and we’re only celebrating the one that has to do with white supremacy.”

This kind of selective memory perpetuates a racist culture, he said, making it more difficult to change the historical narrative.

“What are the role models [young white children] have there? The extremes on white supremacy," he told HuffPost. "It’s so much a part of our culture, how do you break it down?”

The activists HuffPost spoke with have no intention of remaining silent on the issue.

“It’s wrong for them to think that activism will quiet in spite of this 16-year moratorium [on renaming buildings],” said Bishop, who added that he, along with a campus activist group known as the Real Silent Sam Coalition, plans to keep working to make UNC more welcoming of diversity.

Fortune, at Winthrop, said that students at other schools should educate themselves on the namesakes of their campus buildings and monuments. He added that students should educate their peers and, where necessary, meet with those in charge to make change.

“We’re not gonna let this die," said Fortune. "It’s just too important."

Is a building name on your campus being contested? Contact this reporter at alexandra.svokos@huffingtonpost.com.