Not that long ago, George Washington University in the nation's capital became the first university in the country to charge $50,000 per year for combined tuition, room, and board. GWU is located just a few blocks from the White House and owns a lot of pricey D.C. real estate, a fact that prompted one of its law school graduates to suggest that GWU is actually a real estate company masquerading as a university. Putting aside that quip, there is no disputing the fact that for most Americans, $50,000 a year for college is a lot of money, especially when median family income in this country is roughly $52,000.

Today, however, $50,000 is old news. Many colleges and universities now charge above $60,000, and some law schools charge over $70,000. It is no wonder that so many of our young people are beginning to question the wisdom of seeking a four-year college degree if doing so means going deeply into debt and then entering a sluggish jobs market. At the same time that educators, politicians, and business leaders are telling our young people that they need more postsecondary education than ever before to be competitive in a global economy, there's this kicker: "Oh. By the way, you'll have to take out the equivalent of a home mortgage to pay for that education."

A mortgage -- without any guarantee that there's any equity built up after the two-year or four-year investment!

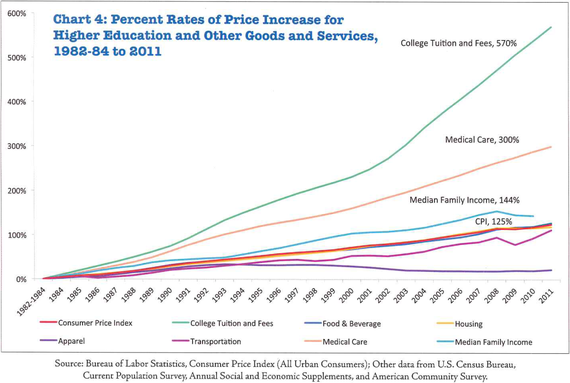

Consider the following chart released by the Committee for Economic Development in 2012:

Reprinted in Boosting Postsecondary Education Performance by CED (2012)

During the last 30 years, the Consumer Price Index has been relatively stable, a fact that is not surprising given the relatively low inflation rate during that period. Health care costs, by contrast, have risen more than twice as fast as the CPI, but postsecondary-education costs have risen almost twice as fast as health care (which everyone knows is unsustainable) and nearly five times CPI growth. Median family income, by contrast, has risen only 144 percent during this period. Once again, the American middle class is being squeezed--priced out of what was once a major component of the American Dream after World War II: getting a college degree.

Some critics will dispute this conclusion because, as they note, not everyone actually pays the full sticker price. When you take into consideration grants, loans, scholarships, and other "discounts," the actual cost-inflation picture is much better.

What this argument suggests, however, is that the pricing policy for American postsecondary education resembles the pricing policy for American health care. At the hospital, the full price of a colonoscopy might be $3,000 (or $5,000, or $10,000), but what an insured consumer actually pays will probably be different, based on factors beyond the consumer's direct control. When major costs are covered by third-party payors, consumer choices are actually distorted, because those choices are not made on the basis of a full appreciation of actual costs. The net result in health care is to create a system that rewards volume over value, thereby making cost-effective comparison shopping that much harder and prices that much higher.

We have created a similar system when it comes to financing postsecondary education. The people who have run our colleges and universities for the last 30 years appear to have been, at best, blissfully unaware of the rising costs. At worst, they have been willing enablers of the cost increases, as long as somebody else was paying the price, loans were plentiful, and federal grants and state subsidies kept rising.

With the onset of the 2008 Great Recession, we saw significant reductions in state tax receipts and an increase in the demand for income maintenance and other state assistance programs. Many states began reducing subsidies to their public postsecondary institutions, thereby shifting more of the direct costs to individual students and their families. Student loan borrowing has grown to such an extent that we now have more than $1 trillion in student loan debt, an amount that exceeds the nation's credit card debt--a fact that became apparent in the summer of 2013.

Today's financing for postsecondary education is fundamentally different from the nation's commitment made in the 1944 Servicemen's Readjustment Act, known popularly now as the G.I. bill. Congress enacted one of the most successful government programs in the nation's history when it provided scholarships to our returning World War II soldiers. Back then, the nation valued highly the public investments made in our "youth human capital." But now we have abandoned that investment model in favor of a debt model. We need to think hard about the direction in which we are headed when it comes to postsecondary education financing.

This is no way to run a complex enterprise that deeply influences our educational system and, in turn, our future economic strength. No other developed country of which I am aware subjects its young people to such financial trauma as a means for them to obtain the education they need to be productive workers and engaged, effective citizens.

For the first time in decades, young Americans are now questioning whether obtaining more postsecondary education is worth the time and expense. This questioning -- no doubt prompted by their totally understandable reaction to the sticker shock -- will further erode the competitive position of the United States when it comes to the percentage of American adults with postsecondary degrees or credentials. The Indianapolis-based Lumina Foundation is working hard to ensure that 60 percent of Americans have a high-quality postsecondary degree or credential by 2025. Lumina's Goal 2025 is directly relevant to our economic success, because we know that 65 percent of U.S. jobs will require some form of postsecondary education by 2020. We need to accelerate our postsecondary attainment as a nation and not establish barriers or disincentives to achievement.

Charles Kolb, a Lumina Foundation Fellow, is President of the French-American Foundation--United States in New York City. He served in the first Bush White House from 1990 - 1992 as Deputy Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy and at the U.S. Department of Education from 1986 - 1990. From 1997 until 2012 he was President of the Committee for Economic Development, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. The views in this article are solely the author's.