NEW YORK -- For Kate Johnson, any job felt better than no job at all.

Shortly after graduating from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Johnson opened up her laptop and began a months-long quest to find work.

Over the course of the summer, while Johnson applied to nearly 50 different jobs, she only ever heard back from eight potential employers. Of the eight, seven rejected her on the spot.

But more difficult than the chronic rejection, Johnson learned to steel herself against the more likely response of no response at all. By the time an Ivy League university offered Johnson an entry-level editorial position, she leapt at the opportunity.

While the starting salary paid less she had originally envisioned, it was an offer Johnson couldn't afford to pass up.

"Searching for a job in this climate was like living through a vast wasteland of rejection," said Johnson, 22, who majored in English and now owes about $22,000 in student loans. "No one understands how truly bad it is out there."

Even with a job, Johnson is hardly the only recent graduate now suffering a wage shock.

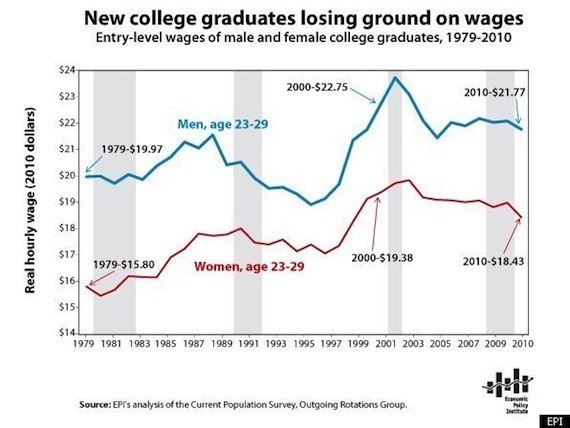

A study released earlier this week by the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal research and policy center, found that entry-level wages for 2010 college graduates were about a dollar per hour lower than what their peers were earning a decade prior after adjusting for inflation.

"Entry-level wages of college graduates have fallen," said Lawrence Mishel, a labor market economist and president of EPI. "People coming out of college now are getting jobs that pay less than what older brothers and sisters got when they finished college."

Although entry-level hourly wages saw gains during the 1980s and 1990s, the past decade was far less kind to younger, college-educated workers. Since 2000, the report found that wages for recent graduates have deteriorated, despite national policies advocating for greater numbers of college graduates to fill an overabundance of positions requiring at least a college degree.

"As everybody knows, when there's a shortage, the price goes up," said Mishel. "The claim that there's been an increased shortage of college graduates is not borne out according to the lower wages they've earned."

Further, between 2000 and 2010, gaps according to gender persisted. In 2010, the report found that college-educated men made an average hourly wage of $21.77, down 4.5 percent from the $22.75 they would have made in 2000. For college-educated women, entry-level wages averaged $18.43 in 2010, while the same women might have expected to make 5.2 percent more, or $19.38, a decade prior. (All wages are in 2010 dollars.)

But despite recent wage stagnation, college educated workers have weathered the Great Recession far better than their lesser-educated peers.

Carl E. Van Horn, a professor of public policy and director of the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University, still sees a "huge premium" for college-educated workers when compared to young workers clamoring for a job with only a high school diploma.

"In an economy like the one we're living in, there really are no safe havens -- even for college graduates," said Van Horn, who sees even recent graduates falling victim to the same wage stagnation now affecting many Americans. "Everyone needs to calibrate, to readjust their expectations to meet the harsh realities that show little sign of letting up."

For rising seniors starting their final year of college, Van Horn suggests that students pursue internships related to their major and chosen vocation, in addition to taking courses that might contribute to their future employability.

"Now's definitely not the year to decide to slack off, or to enroll in a class based on the fact that you don't want to go to any morning classes," said Van Horn. "You have to be careful and thoughtful in an economy like this one. The competition is really very tough."

While the EPI report hardly indicated that it's no longer worth going to college, Mishel cautioned that a college degree is increasingly looking like less of a guaranteed ticket to the middle class.

In terms of duration, the report's conclusion didn't mince words: "With unemployment expected to remain above 8 percent well into 2014, it will likely be many years before young college graduates -- or any workers -- see substantial wage growth."

Mishel mentioned that graduates who finish college during periods of economic recession tend to earn less not just in their first jobs out of school, but over the duration of their entire working lives.

"Given the high, persistent unemployment rate, this is going to create a permanent scar for these young people," said Mishel. "We're looking at a whole generation beset by these problems."