On April 23, 1949, during the Chinese Civil War, Mao's People's Liberation Army (PLA) captured the city of Nanking, now known as Nanjing, then capital of China and headquarters of the Nationalist Party (also known as the Kuomintang or KMT). Though fighting would continue for the rest of the year as the KMT retreated to southern China, and ultimately Taiwan, this victory signaled the inevitability of Nationalist defeat and the end of the Chinese Civil War. Leonard L. Bacon was stationed in Hangzhou in 1948 and transferred to Nanking just prior to its occupation by Communist forces.  Read the entire account here. This account was compiled by C. Bradley.

Read the entire account here. This account was compiled by C. Bradley.

BACON: [In early 1948] the general impression though was not so much of fear, or support for communists, but a general feeling that things were going slowly worse, and worse, and worse under the Kuomintang.

On everybody's mind, of course, was inflation. It was enormous. The Consulate [in Hangzhou] had difficulty getting the money out to pay the staff every week. It would come in these yuan notes tied in bundles.

Nobody ever counted the notes in the bundles, it would take too long for what they were worth. As soon as we paid the staff each one would run out on the street and buy salt, which was simply something that had some stable value.

At one time the plane from Shanghai which carried the money, failed to arrive and the Hangzhou police didn't get paid. What they did was to take direct action which didn't get them any money either, but they went to the branch of the Bank of China and demolished it. They simply tore it down, leveled it to the ground.

There was almost no support for the Kuomintang except something that might stave off the Communists for a while. But in the course of the year even that changed where people looked forward to the arrival of Communists as putting an end to an almost impossible life that they were leading.

We were concerned about, of course, the missionaries scattered around northern China, and wanted to get messages out to them saying, "It's probably time to pack up and get out." This, however, would have created a certain amount of panic, and also greatly offended the Nationalist government which was maintaining that there was no danger, everything was secure.

So there was a great problem of getting out a message which would indicate that while the situation is unsettled, and so forth, anybody who is planning shortly to leave for the United States on leave or whatever should do so promptly and trust that the situation will otherwise clear up.

And finally when I got leave to do so I notified missionaries in certain places that it was probably time to move, and I got one or two hot replies that said, "Why didn't you tell us sooner? We've been waiting to hear from you. We expected to be warned." But our position had been just reversed; we didn't want to warn too much because that would result in collapse of morale of the Americans there and consequently of Chinese too.

Our attitude officially was that nothing much to worry about-no cause for alarm -- don't get panicky. The time came, of course, just before the capture of Nanking, when the government itself moved to Canton [now Guangzhou]. Our Minister Counselor, Lewis Clark, moved there with a small staff. The Ambassador and the rest of the Embassy stayed in Nanking mainly because, I think, we wanted to be in touch with the Communists if they came right in.

[People] constantly were hoping that the Chinese military, the Nationalists, would have some successes, but city after city kept falling; first in Manchuria-that was the second big one there. Then cities around Peking, and finally Peking and it was felt that, "Well, they'd be stopped at some places between Peking and Nanking. We can hold them for a while."

But the Nationalist army had the idea that if they could hold the cities they could eventually tire out the Communists. But this had been a failing policy for years, and years, and frequently instead of holding the cities, they would abandon them at the approach of the Communists.

This happened, of course, at Nanking. It was generally supposed that the Yangtze River, being a mile wide, would be an absolutely impossible barrier if there were any kind of defense at all. Well there wasn't any defense, and I recall very well as I guess most of the people Embassy do, the morning when we discovered that the Communists were already in town.

This was in April 1949. The walls of Nanking are over 20 miles in circumference, 30 to 40 feet high-of course, they're made of bricks so they could have been blown up but there was no need to do that. The gates were left open; the Communists walked in.

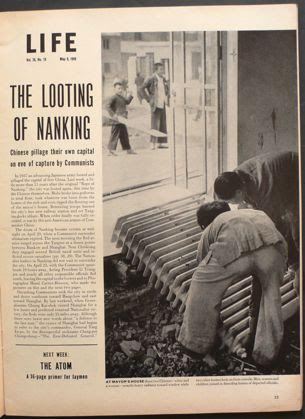

The Chinese government, and the police, had left town the night before knowing what was going to happen. There was a certain amount of looting that went on, some rather comical. I remember seeing some poor Chinese coming away from the Chief of Police's house with a water closet on his shoulders-absolutely no use to him, he had no water supply but it was a pretty impressive object.

What was really comical was that a few weeks later in the fall, the communist government decided to make a historical event out of the capture of Nanking. We could see the cameras being placed on the top of the walls, the army approaching with scaling ladders, soldiers climbing up and getting on top of the wall, waving the flag, and everything else-something like the Berlin wall thing. And none of which, of course, had ever happened. They just walked in. We wouldn't, of course, treat them as the government of China until Washington decided, but that was considered to be pretty much a foregone conclusion, and...Ambassador Stuart felt that he would be in a very strong position to inform Washington as to what the Communists were thinking, what their plans were.

We wouldn't, of course, treat them as the government of China until Washington decided, but that was considered to be pretty much a foregone conclusion, and...Ambassador Stuart felt that he would be in a very strong position to inform Washington as to what the Communists were thinking, what their plans were.

At this time it seemed possible apparently that a kind of a modus vivendi could be reached between the Nationalists and the Communists. There might be a national congress composed partly of communists and partly of Kuomintang. After all, that's what the elections had been supposed to anticipate.

But, of course, with increasing successes the Communists were less and less interested in that, and it became apparent to them if to nobody else, that before long they'd have the whole country. So Ambassador Stuart...eventually decided that he would have to go to Washington on consultation...

In fact, it was quite clear in the beginning of 1950 that they wanted all foreigners out of the interior of China. A few, necessarily, in Shanghai and Canton for trade, but otherwise the whole of China was going to be a closed box, with no foreigners except Soviets admitted.

This was in March of 1950. By that time the Consulate General in Peking had been closed. All the Consulates in the interior of China had been closed. Our staff, what was left of it in Nanking, had proceeded one by one to Shanghai awaiting shipment and as it turned out I was evidently the last one to leave Nanking.

So finally we were all in Shanghai and waiting for transport out. The Kuomintang had said they'd mined the mouth of the Yangtze and the harbor of Shanghai. It was probably not true; I don't think they were capable of doing it, but they said they had.

And as a result no commercial vessel would venture in, no matter what. So finally it was arranged that the General Gordon, which had been a troop carrier, would pick us up at Tientsin... which [then] went to Hong Kong, and at Hong Kong the President Wilson, I think was the ship that carried us back home.