In a digital-era where "sitcom writer" sounds almost as contemporary as "telegraph operator" or "CompuServe tech support," I was astonished to realize I just finished my 21st show in 20 years. Or as my writing partner pointed out, if we were comically and racially mismatched buddy cops, we'd be one week from retiring to a sailboat. Worse, we may actually be at an age where we are too old to be "too old for this shit."

Before I broke into sitcom writing, the idea of someone finishing their 20th season conjured up images of jowly alter kockers, with names like Sy or Hy or Sidney, eating sky high tongue sandwiches and pitching jokes dripping in Borscht juice and Vaudeville rhythms, recounting tales of how they transitioned Fibber McGee and Molly from radio to TV. Guys (and one girl) whose reruns are available on kinescope at the broadcast museum. Not on Amazon Prime. You know who I didn't picture? Me. Now. I can't be a grisled twenty-year vet dispensing career wisdom. I wear Pumas. I listen to Pavement, for chrissakes. I could've sworn I just got here.

Early on, twenty years seemed like such a vastly overlong career, that in most writers' rooms I've been in, there's a running joke that you can add "My twenty years in Hollywood" to any imaginary memoir you're writing and it's inherently more interesting and salacious. Try it. "Blowing Sailors and Eating Cashews"-- I have no idea what that means. "Blowing Sailors and Eating Cashews: My Twenty Years in Hollywood"-- I still have no idea what that is. But there's no way I'm not at least clicking on the free sample.

You'd think that after 20 years, I'd have acquired some over-arching universal theory that explains the television universe. You'd think, but you'd be wrong. Would you settle for a handful of not-so-trenchant observations? 1. All comedy writers think it's funny to say "guv'nor' in a Cockney accent. And all spouses don't. 2. Shows where you work till 6 in the morning are no better and usually significantly worse than shows where you stay till 6 at night. 3. Don't work for someone going through a divorce (see #2). 4. America loved multi-cam sitcoms, so networks stopped making them. 5. If you eat peanut M &M's every minute of every day, you might gain weight. 6. TV executives enjoy buying shows from tall men who live near the Palisades. Then again, they may live near the Palisades because they've sold shows. Or because they're tall men. Did I mention, it isn't a very well-formed theory?

But there have been a couple things that've surprised me more than others. First, 99 per cent of television comedy writing doesn't involve writing television comedy. I became a writer assuming I'd get to be an eccentric hermit who only spoke to another human when turning in my Daily Grill order. Imagine my surprise to learn that shows are run like comic jury duty. Ten to twenty hours a day locked in a room with 11 comedians and one person oddly fixated on punctuation.

The other enormous surprise (besides my wife not laughting at "guv'nor") is how much of writing is a journeyman's existence. There are exceptions--people who wrote one pilot, syndicated and now tool around Montecito in their solid gold dune buggies, making fun of Oprah and their other poor neighbors. But for most, the career is that of a comic mercenary. A gun for hire with a laptop and an automatic Lexapro refill from Express Scripts, spending the money you made on the last job, while waiting to find the next one. The truth is, everybody wants to be a star. But most people, if they are as fortunate as I've been, just go to work and are thankful for the chance.

Let's be honest, nobody sets out to a journeyman. No one dreams of becoming an uncredited session guitarist or an itinerant middle reliever used only in certain righty-lefty situational matchups. The same is true for TV writers. When you break in, your biggest fear is where will you put all your various Emmys and Golden Globes and thank you notes from America? That's a fear gradually replaced by 'what are ulcer symptoms" and "where is Valenica and who thought to build a studio there?'

Twenty years is long enough to have seen massive changes and to realize that fear of massive change is usually overblown. I've lived through the death of the sitcom and its inevitable re-birth. I've survived the game show bonanza, the singing show bonanza, a remake of Bonanza, reality TV, streaming services and Jeff Zucker.

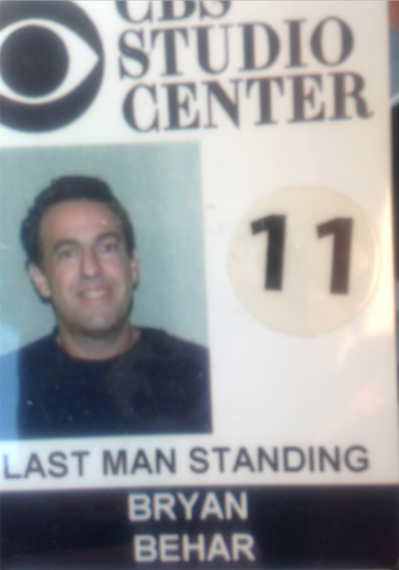

I've had every experience imaginable. I've written on single-cams, multi-cams, cartoons and dramas. And have had more pilots killed than Malaysia Airlines. I've been on great shows that never aired. And some shows that you can't believe did air. I've been on programs that featured talking babies, talking frogs, talking boxing kangaroos and two shows with talking dogs (only one of which took bong hits and spoke with an Australian accent). I was on Working, Working Class and Work With Me and am as surprised as you are to learn that these are three different shows. I wrote for Andy Richter Controls the Universe and Baby Bob, the same season, on the same lot. It was like if Brian Wilson had recorded Pet Sounds and Kokomo in the same session.

And I'm not knocking any of these. Baby Bob is, by far, our highest rated credit. And every one of these shows made it through the unimaginably impossible pilot gauntlet. They had pitches that were bought, pilots that were shot, shows that made it on to the fall schedule. And nobody selected them because they assumed they weren't the next Cheers or Friends. Heck, these days they'd be ecstatic if they had the next Suddenly Susan.

Plus, like anyone in any field, you go where the work is. You may enter comedy, because you have an outsider-y, underdog voice and view of the world. Then one day you wake up and realize you're writing a show that celebrates philandering CEO's. Or writing vituperative rants for Tim Allen mocking gun safety And you think how did I get...here? The answer is, "I have a mortgage." And "I already cashed my bar mitzvah bonds." The days of "I don't know, this job doesn't match my incredibly specific political agenda and comic sensibility" have long since passed. If they ever existed.

This isn't one of those screeds decrying ageism in entertainment. The truth is, on my last 3 shows, I'm pretty sure the median age was "dead." I wasn't the youngest person on staff, but, there were enough people older that I could almost non-ironically be referred to as "The Kid." There are days I'm surprised they didn't send a shuttle to pick up the staff at the Motion Picture Home.

I guess my biggest takeaway from two decades in The Business is similar to my takeaway from life: I assume things will work out. Or they won't. Then I'll try something else. It's about accepting that a majority of this business is failure and that's different than letting yourself feel like a failure. You do need to have a little (or a lot) of Charlie Brown in you to do this job. Always hoping that the next pilot will get shot, the next movie will get made. I couldn't have predicted what my first twenty years would be like. I have no idea what's coming. Maybe they'll zap TV directly into a chip in our brain, all Johnny Mnemonic-style? That's what I'm rooting for. But as long as they keep making comedies and keep needing people with absurdly damaged childhoods to write them, I'm excited to see what the next twenty years will bring.