"A great battle lost or won is easily described, understood and appreciated, but the moral growth of a great nation requires reflection, as well as observation, to appreciate it." -- Frederick Douglass, January 13, 1865

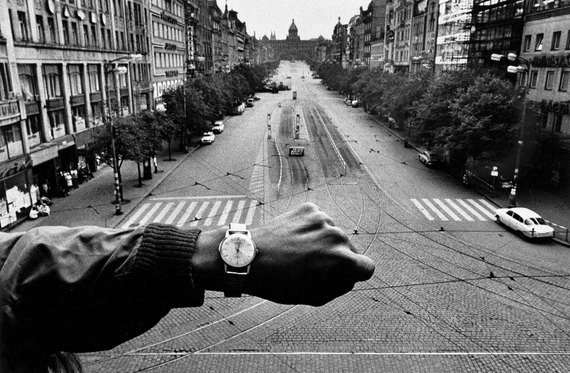

Prague, 1968. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of private collector. © Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

Observation is a defining practice of the lens-based artist, and the photograph (or film or video) is the record of that observation. The truth of that record, however, has been thrown into question since the medium's inception. Photographic manipulation was and remains commonplace, whether for commercial, artistic, propagandistic or, in the era of the selfie, straight-up egoistic reasons. The American Civil War -- the subject of Frederick Douglass's speech 150 years ago -- and subsequent conflicts throughout the world have been rife with examples. And today's cameras are designed to make photo manipulation, even for amateurs, easier than ever. It's a function seamlessly integrated into every smartphone, and Instagram is its apotheosis.

Enter Josef Koudelka. Fully engaged artistically and intellectually at 77, the legendary Czech-born photographer maintains a profound belief in the truth of the photograph and, perhaps more precisely, in the truth of the photographic negative. (He's not alone. See Negatives, the new book of photographs by Chinese artist Xu Yong, who chose to publish his pictures of the 1989 pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square in their raw form, as negative images, because, as he told The New York Times, "negatives never lie.")

Koudelka's work emerged on the international scene before he did -- his iconic images of the August 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Prague and its people's ultimately futile resistance, were smuggled out of the country and, for his protection, published anonymously. In 1969, the still unnamed "P.P." (for Prague Photographer) was awarded the prestigious Robert Capa Gold Medal by the Overseas Press Club. He has been associated with Magnum photo agency since 1971 and became a naturalized French citizen in 1987.

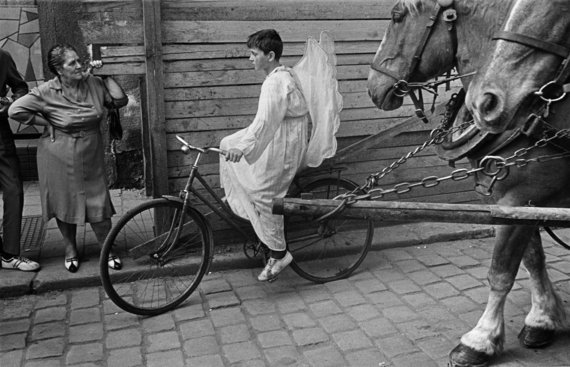

Czechoslovakia, negative 1968; print 1987-1988. Image courtesy of Josef Koudelka and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York. © Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

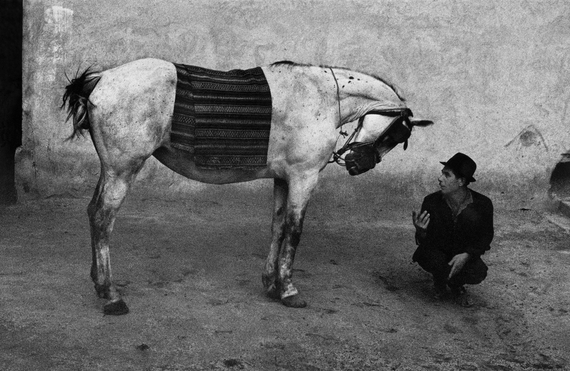

Throughout the 1960s, Koudelka spent time in Roma, or Gypsy, communities and they became a longtime subject of his work. He made thousands of images, paring them down to hundreds and eventually dozens. This body of work, published in the 1975 Aperture monograph Gypsies, was my introduction to Koudelka. His vision -- its immediacy and its mystery, its textures and shadows, its fundamental humanity -- felt familiar to me in a way I had not been able to articulate until I had the opportunity to interview the artist recently in Los Angeles, where his first U.S. retrospective continues through March 22 at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

In person Koudelka reminded me of my father, both of them peripatetic exiles, restless and wiry, outgoing yet wary, buoyed through life by force of personality and ambition, enlisting supporters as they go. They even favored the same style of multi-pocketed khaki vest, always ready for action.

Koudelka was born in the town of Boskovice, in Moravia, in 1938. He trained initially as an engineer, played music, and began working in theater as a photographer, going on to become a world-renowned, fiercely independent master of the medium.

My father was born in Marko, Hungary, four years earlier and 200 miles south. He grew up on a farm but had a knack for science and languages that led him, later, to work as a chemist and ultimately a career as an educator and travel entrepreneur. He passed away in 2008.

Both men's childhoods were marked by the chaos and privations of World War II. My father was 10 when the war ended, and in short order the Russians appropriated his family's farm, relocating them and their neighbors to a distant Kolkhoz (collective farm). It was a rupture that could not be mended. In 1948, my father fled on foot, alone and in secret without telling even his parents, across the closed border to Austria. After a decade in a Hungarian refugee settlement in southern Germany, where he also earned an agricultural degree, he emigrated to the U.S. and became a naturalized citizen.

Despite the ostensible protection afforded by his new U.S. passport, my father was fearful returning to Hungary for the first time, with his wife and five children bundled into a rented white VW van. It was the summer of 1968 and I was seven years old. I had never been behind the Iron Curtain -- did I even l know what that meant? I do remember armed soldiers and a long wait at the border in the heat, our dark blue passports handed through the van's tipped-open windows, and my parents' quiet trepidation, speaking only when questioned. Not understanding the language made it all the more sinister for us kids. Finally, we were allowed to pass.

Sukop family photograph taken in Hungary in 1968. In the front row: Sylvia, age 7, in a flowered dress. In the back row: The first three adults are her father Paul, mother Hedwig, and uncle Jószef. © Sylvia Sukop

The rest of that trip, spent among relatives in rural Hungarian villages, was a primal visual experience. A second-grade Catholic schoolgirl emerging from the relative confines of suburban Reading, Pennsylvania, I had never felt so sensorially engulfed. The images remain vivid, though not all were captured on film. My father's stepmother in baggy dresses, stooped but smiling, her thick black eyeglasses made for a man; my quiet uncle Jószef, a truck driver and farmer, and the gentle way he had with his three children, my all-of-a-sudden cousins. A small barnyard beside the house, chickens chased, beheaded, boiled and plucked, blood and white feathers, and a wooden outhouse instead of a regular toilet indoors. Long, dimly lit evenings, extended family in loud conversation around too-small tables, fiery home-brewed Schnapps and sweet Lekvar cookies. A drafty old church, out-of-tune hymns echoing off the walls, sad priest flinging clouds from an ornate incense burner and, in miniature vestments, altar boys not much older than I. The walk down the road to the village cemetery, moist brown snails clinging to a weathered headstone and on that stone the last name Szukop, including the 'Z' my father had left behind when he became an American.

This intense Old World -- passionate, hardscrabble, communal, scarred by war and poverty, yet bursting with camaraderie, uplifted and uplifting -- was mine, but I was too young and my visits too infrequent to truly possess it. Encountering Koudelka's books as a young adult, first Gypsies, later Exiles, brought that world back to me. I bought a poster of the man crouching beside the horse, the two seemingly in conversation, and lived with it in every apartment over the next three decades. And only now do I realize this iconic photograph, Romania, was taken in 1968, the same politically charged year that I first visited Eastern Europe, forever imprinted by the experience.

Romania, negative 1968; print 1980s. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of Robin and Sandy Stuart. © Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

The impressive exhibition currently at the Getty, Josef Koudelka: Nationality Doubtful, encompasses more than 140 photographs and books, from Gypsies and Exiles and the Prague '68 series, to the more recent, large-scale panoramic work, including Wall. Completed in 2013, Wall documents Israel's controversial West Bank barrier and the distressed landscape that surrounds it.

For a man without a nation, Koudelka is a keen observer of its harsher mechanisms and the brutal toll they exact, not only on "moral growth" (to borrow a phrase from Douglass) but on people's ordinary everyday lives.

I sat down with this famously nomadic man, for whom sitting does not always come easily, in a meeting room in the museum's Photographs Department. Occasionally refreshing his cup from a pot of hot tea, Koudelka spoke -- exacting in his choice of words, but not without moments of levity -- of his early years, what drew him to document the Wall, and why he embraces the digital revolution.

You were born during the war, a time when Jews and Gypsies were persecuted and killed. Did you know Jews or Gypsies growing up?

I was born in a little village. There were no Gypsies and no Jews in the village. I didn't know much about Gypsies and nothing about Jews. Gypsies I got to know later, when I left the village, but strangely enough I became more conscious of Jewish people only when I left Czechoslovakia. When I came to New York, for instance, the first question I was asked was, Are you Jewish? People got very disappointed when I said no. Nobody from the family? Your mother, maybe grandfather? Then the next question was: How is it possible? You are in Magnum, you are a good photographer -- and you are not Jewish? [Laughing.]

What are your memories of the war?

My memories of the war are of German soldiers coming to my village, and people being taken away and never coming back. I also remember waking up one morning and seeing a dead body of a partisan in front of my house. My parents who usually listened in the evenings to the BBC broadcast for Czechoslovakia were afraid that the German Gestapo might come, and if they only touched the radio and it was warm they could be sent to the concentration camp. Then I remember the Russians coming in '45, as liberators. I saw my first cinema when the Russians came. They projected it in the meadow behind the village.

So this sense of disruption, of exile, came for you even earlier than 1968?

It is possible that if the Russians hadn't invaded in 1968 maybe I would have never left Czechoslovakia. It is possible, but I can't know.

That's how my father felt -- if the Russians hadn't come he might not have left Hungary. Where's your home base today?

I have two places, one in Paris and one in Prague, which I consider more as working spaces than the places in which I live. Most of the time I am only passing through Paris, and to Prague I go only to do certain work. I have been traveling during these 45 years and I never stay in any place longer than three months.

In terms of the project in Israel and Palestine -- This Place -- I know you were invited by Frédéric Brenner to participate. Why were you drawn to making your project, Wall?

On the one hand, I was interested in seeing Israel because I had never been there, but on the other, I really didn't want to go there as I was not sure if I could do something good and manage to follow it through to the end in the way I thought it should be done. So for that reason when Frederic approached me, I said no. But finally I accepted his invitation on the condition that I could come for two weeks, just to see what it is about, and that I would pay for the airfare myself. I was so sure that I was going to refuse to participate in the project, that I didn't want to feel any obligation to him. However, it happened that during this first trip I saw the Wall.

Seeing the Wall changed your mind?

I grew up behind the Iron Curtain, like many people in Eastern and Central Europe. All my life I wanted to go behind the Wall, to go on the other side. But in fact I never saw the Wall. It was difficult to get close, they wouldn't let us. To try to get close meant that you are trying to escape. But in spite of that the Wall was present all the time in my mind. I wanted to get out of the cage, to see what was on the other side. I knew that what they were telling us was not true, that they were trying to manipulate us. I wanted to learn for myself what the truth is.

Did you set any conditions before committing to the project?

If I accept a commission that interests me, I want to know where the money comes from. This is a basic condition concerning whatever I do. I don't want to be sponsored by money which origins' I don't know or money that might be connected to the arms industry, cigarette companies or anything similar. If someone gives you money, many times they intend to control what you do and if someone invites you to photograph something and pays you for it, you might feel a certain obligation. In the case of This Place it was no different. I was assured that I could photograph what I want, the way I wanted to photograph it and that the money came mainly from private American-based foundations. I was also guaranteed that none of the money came from the State of Israel.

One of my main conditions was of course to photograph both sides [of the Wall]. In fact, what I realized is that gradually the Wall is taking on the characteristics of a unilateral imposed border, replacing the internationally recognized Green Line. Already much of it runs inside the West Bank itself, on Palestinian land.

You know, it's difficult to talk to people about the Wall, because anybody can have their own truth about it. There are several reasons for building the Wall, and sometimes people pick up the one that suits them the most. But it is much more complicated. A wall means a failure of society to solve certain problems. It doesn't guarantee security.

Were you able to photograph on your own? Did you encounter people at the Wall?

In Czechoslovakia I couldn't come close to the Wall. The situation is similar to what happens today in the West Bank. If a Palestinian person approaches the Wall it might mean he is running into trouble.

I was accompanied by the young Israeli photographer, Gilad Baram, who was also documenting our travels together. As I was discovering Israel and Palestine, he was discovering his own country too. This discovery changed him profoundly.

So you saw more of the Wall than most Israelis do?

I went to Israel and Palestine seven times, usually for about three weeks, and from morning until evening I photographed the Wall and the area around it. I saw more than most people who watch television or read the newspapers see. I believe I saw more than many Israelis see, as most Israelis try not to see the Wall. One Israeli poet told me when he saw my book: "You did something important. You made the invisible visible."

What kind of impact do you hope to achieve through the Wall project?

I am very skeptical about the power of photography. I don't expect anything [from publishing Wall]. I'm just showing what I saw. That's it. I am not sorry that I went to Israel and Palestine because I think it was important to document it. In the case of This Place, it was a process of learning what it is about. When I finished the work I had a good feeling -- I couldn't do more and I couldn't do it better.

For me, Israel and Palestine are a fascinating place. There are so many brilliant people there, so many sensitive people and so much energy. But it is a very sad place too. I have the feeling that many Israelis realize today that they have become what they didn't want to be.

You now use a digital camera. What has that transition meant for your work, and your working process?

Wall was my last project made completely on film. It was Kodak-sponsored. It is important to have it on film so nobody could deny that it existed. It is part of history. It was there and I photographed it as my eyes saw it.

To me the most important thing is to continue to photograph. I am 77 now and I still enjoy taking photographs. This might not be completely normal. When I met Cartier Bresson he was 62 and in that time he was already losing interest in photography.

Digital photography helped me to go ahead with my work. It helped me not to be dependent on sponsors which for my panoramic pictures I would usually have to be, even if just to buy the film, develop it and make the contact sheets. When Leica made a digital panoramic camera for me -- which gave me a similar result to the analogue camera I was using before -- I was very happy, because now I could pick up my camera, call my friends which I have all over the world, and just say, Can I sleep in your house? I made a few trips with both cameras in order to test the digital one. I found that on the last two trips I was actually taking more pictures, and enjoyed it more, when I was using the digital camera. I no longer need to carry with me 35 kilograms, only about 10 kilograms, and I don't need to go through the X-ray machines which I really dislike. So the digital camera makes it easier, and also more interesting. I am 77 and I can say, Vive la Revolution! [Laughing.]

Since you travel constantly, having a place to take care of your work is important. I understand Magnum has been that place for you.

Magnum was extremely important for me since I left Czechoslovakia. I made friends there, it was my home and it was my address.

I see you're wearing a digital watch and I am reminded of your famous watch picture from Prague '68.

When digital watches first came out I was with [fellow Magnum photographer] Cartier Bresson. I had just bought this cheap digital watch. I said to Bresson, I have this fantastic watch. It can wake me up! He looked at his Swiss watch and said, Let's exchange! So we did. Two days later I came to Magnum and the digital watch was on my shelf, so I took off the Swiss watch and put it on his shelf. [Laughing.]