The U.S. Senate just issued a report that said torture doesn't work. It confirmed a mountain of research from academics over the years that reached the same conclusion.

Senate investigators revealed, in a lengthy summary of an even lengthier report, that enhanced interrogation tactics adopted by the CIA that are seen as tantamount to torture weren't just illegal. They were ineffective, according to the CIA's own assessment team.

But had they read the works of academics who have researched the subject, they might have known better. They would have avoided the legal and ethical quandaries, and perhaps received better intelligence that could have helped us capture more al Qaeda and Taliban leaders (some are still on the run today) as well as disrupt their networks accused of engaging in further acts of terrorism.

Game theory research by John W. Schiemann at Farleigh Dickinson University for Political Research Quarterly also found torture to be unreliable. A Science Daily article about his research states:

Schiemann stated that while many believe that interrogational torture cannot be justified under any circumstances, those who do advocate for it claim that at times it is the only way gain critical information. He found, however, that under realistic circumstances interrogational torture is far more likely to produce ambiguous and false, rather than clear and reliable, information. "The use of torture makes it possible to extract both real and false confessions and no ability by the state to distinguish the two," wrote the author.

Schiemann's research echoes the findings of another professor, Darius Rejali of Oregon's Reed College. In an article in Live Science, Heather Whipps writes:

"Torture during interrogations rarely yields better information than traditional human intelligence, partly because no one has figured out a precise, reliable way to break human beings or any adequate method to evaluate whether what prisoners say when they do talk is true," [Darius] Rejali wrote in a 2004 article on Salon.com.

As a Washington Post article notes, torture didn't help the Nazis or Japanese military break a series of resistance movements in occupied states. They didn't help the French monarchy get much information about the revolution. Torture doesn't always make people talk, and when they do, it can yield no shortage of false leads from those who don't know anything. Others just tell the torturers what they want to hear, so if the torturers are wrong, we get events like years of fruitlessly scouring Afghan caves for Osama bin Laden and Mullah Omar.

How do we know these academics were right? Consider what the report found, according to Ken Dilanian and Bradley Klapper with the Associated Press.

For all the effectiveness in breaking detainees' spirits, the "enhanced interrogation techniques" didn't produce results where it really mattered, the report asserts in its most controversial conclusion. It cites CIA cables, emails and interview transcripts to contradict the central justification for torture -- that American lives were saved and terror plots stopped through the information that detainees gave only when subjected to very harsh methods.

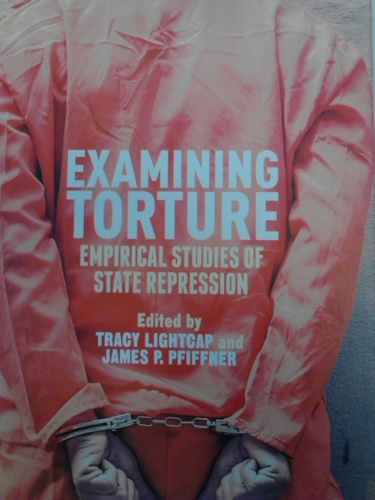

But the CIA didn't have to listen to academics on the subject. They could have read their own research from 1963. In this manual, the CIA concludes "intense pain is quite likely to produce false confessions, concocted as a means of escaping from distress. A time-consuming delay results, while investigation is conducted and the admissions are proven untrue," according to George Mason University professor James P. Pfiffner in his book Examining Torture, co-edited with Dr. Tracy Lightcap.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Tracy Lightcap.

John A. Tures is a professor of political science at LaGrange College in LaGrange, Ga. He can be reached at jtures@lagrange.edu.