Habitat Edges and Design

In design studios and planning conversations that I have had, I frequently make the argument that larger, circular patches are better than irregular-shaped patches. This is because "specialist" species are more vulnerable to edge effects than "generalist" species. Generalists are species that will eat a variety of items and live in a variety of habitats. Generalists can adapt to new food sources and changing landscapes. Think about house sparrows (Passer domesticus) and European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). These exotic birds are found throughout many countries and are outside their natural range in Europe, but they are doing quite well in urban and agricultural areas. Specialists, on the other hand, are much more specialized or particular in their food and shelter requirements. They will sometimes only eat a few types of food and live in only one type of habitat. They do not adapt well to changes in their preferred habitat and will go extinct locally (i.e. extirpated) when their habitat changes. Most species that are listed on the U.S. endangered and threatened species list are examples of specialists.

Figure 7 Riparian edge next to agriculture Photo Credit Geoffrey Fricker, Univ. of California Agriculture

Specialists are most vulnerable to edges. Specialists living in habitat edges tend to encounter higher levels of predation, damage stemming from human disturbances, and increased competition from other species; thus they tend to avoid edges. Specialists typically do not do well in fragmented areas consisting of relatively small, remnant patches. In fragmented areas, small natural remnants are not buffered enough against human disturbances and are more exposed to traffic, noise, and artificial lights. How far the edge effects extend into a patch is variable and depends on the species in question, the type of disturbance, and the types of vegetation found along an edge. It can extend hundreds of meters into a patch even for small birds; for example, Varied Thrushes (Ixoreusn aeviu) had lower relative densities up to 140 meters into a patch than in areas further than 140 meters.

I have heard from many landscape architects that they think edges are good because they increase biodiversity. Well, yes and no. It depends on the situation. Yes, in most instances having lots of edges tend to increase the diversity of species, but the increase is due to the increase in generalists and exotic species that are more adapted to edges and urban conditions. Thus, in reality, having lots of edges favors generalists that are doing well anyway in a region and conservationists are more concerned about impact of urban areas on specialists.

Wildlife corridors and design

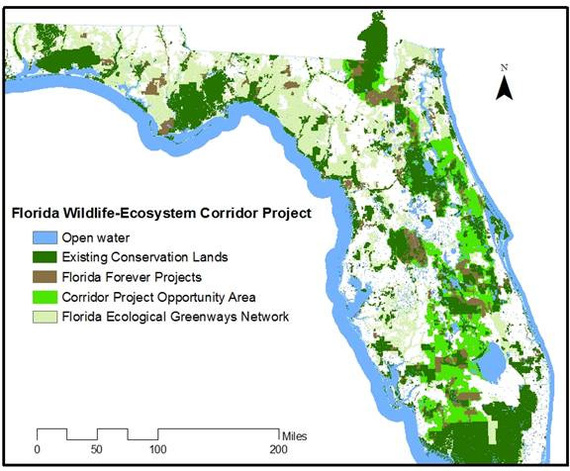

Figure 8 Florida Wildlife Corridor Initiative

Another common application of ecological principles into urban/rural design is the establishment of corridors for wildlife. Corridors are placed to connect patches within a development or outside of the development. The idea is to promote movement of wildlife species across the landscape. Again, this application begs the question, "For which wildlife species?" However, rarely is this addressed during discussions.

As discussed above, scale matters, even for connectivity. How wide is wide enough? A corridor needed for a bear is much wider than what is needed for a mouse. For wildlife, corridors can serve two purposes. First, connections allow animals to reach diverse habitats within their home ranges; and second, at a broader scale, connections permit occasional movements between somewhat isolated populations of wildlife (i.e., metapopulation theory). But are we talking about movement of panthers or insects? For those that are edge-avoiders (e.g., many specialists species), a corridor may not act as a conduit for specialists if it is narrow and mostly edge. In some countries, linear corridors are not really needed but "stepping stones" of vegetative patches could act as corridors. For example, New Zealand is devoid of native, terrestrial mammals (save a few endangered bats); ecologists talk more in terms of "stepping stones" of restored and remnant native vegetation to help improve the spread of native, animals across a landscape.

Any natural connection, no matter how small can benefit certain species (think insects, toads, and salamanders). But before a design is made (and space for development given up), a thorough understanding of local, regional, and migrating species (and their habitat/dispersal needs) should be acknowledged and addressed in the design of a project.

What does all this mean when making planning/design decisions?

Figure 9 Master site plan for The Woodlands at Davidson, North Carolina, which contains a wildlife corridor down the middle. Courtesy of the Lawrence Group.

From the discussion above, one might conclude that only large, connected patches of vegetation are worth saving in a design. However, if you reduce the scale of your thinking, any natural patch can benefit biodiversity and animal species, no matter how small and isolated. While such patches may have limited appeal for some of the larger animals and the specialists, they may still serve as habitat for smaller species such as lizards, frogs, and insects. They could also serve as temporary refuge for migrating animals (e.g., stopover sites for migrating birds). Not to mention plant diversity as well and the multitude of soil biota that occur in small, conserved remnants! But if one is considering large patches, and large corridors, for relatively larger animals, a discussion must ensue about which species these patches would likely benefit. Policies that impact land use maps (generally at broader scales) and policies that address land development regulations (i.e., policies that operate on landscape structure at smaller scales) should be considered in the context of affecting large to small species.

Overall, such discussions will help make transparent the wildlife benefits of a development design at both small and large scales. For example, that Red-tailed hawk appearing in a backyard is contingent on individual lot designs (e.g., leaving those large snags or trees for nesting), available habitat in a neighborhood (e.g., land development regulations that addressed conserving remnants and using native plants in landscaping), and city land use maps (i.e., plans that address the juxtaposition of open space and built areas). There is a direct connection between the design decisions made at different scales and the distribution of wildlife species within a region!

As I have mentioned in my other blogs, design is important BUT IT IS ONLY THE FIRST STEP. What goes on around conserved patches and corridors, such as nearby land uses, can have heavy impacts and prevent wildlife from utilizing these habitats. Think of invasive exotic plants spreading into remnants and corridors, fertilizers running off properties and entering wetlands, and nearby residents illegally using these natural areas for all-terrain-vehicles. The management of these patches and corridors are just as critical, even more so when situated near urban dwellings. Funds are needed to do prescribed burns, trash pick-up, invasive exotic control, and other management practices. Urban patches can attract a variety of wildlife, if they are managed appropriately. Good design is not enough, it must be combined with good management.

Figure 10 Hooded Oriole Photo Credit Walter Kitundu

Further, residents must be engaged as they are (by default) the long-term stewards of the conserved areas. Part of a design project could include education and engagement programs that include the installation of educational kiosks that help educate residents about the importance of managing their own homes, yards, and neighborhoods in an ecologically sensitive manner.

Thus projects that could contain natural patches and corridors for wildlife, design professionals should be trained about long-term management options for their designs. Nearby built infrastructure should be designed with the idea of limiting impacts on natural areas -- for example, limiting the amount of lawn and incorporating more native plants into a landscape would minimize impacts. The context and site conditions for each development will dictate the optimal design. Perhaps, for instance, it may behoove one to fill in wetlands in order to conserve larger patches. WHAT? I can hear the protests now. However, filling in wetlands may work to avoid this scenario: if all, small wetlands were conserved, than a more fragmented landscape containing wetlands and conserved upland areas would be surrounded by built landscapes and prone to daily impact by nearby homes and streets. Designating larger conserved areas, separated as much as possible from built areas, would make management of the conserved areas easier, and such a design helps buffer against impacts stemming from built areas, in part by reducing the edge effects discussed above. Each site is different and opportunities exist at different scales to benefit local, regional, and even global species. Collaborations between ecologists and built environment professionals can help to create "doable" wildlife conservation goals for a site, whether it is focused on specific species or general biodiversity conservation. Such collaborations will result in optimal designs for wildlife conservation. However, we must put management on the same pedestal as design. Successful projects will only come about when "optimal" ecological design is combined with "best" ecological management practices.

This blog originally appeared in the Nature of Cities.