He gave me a list of friends around the state whose work and values align with mine. Then, he asked me to call each one of them and begin the conversation by saying, "hi, this is Lamees, William Winter's friend."

That may be one of the greatest honors I ever receive.

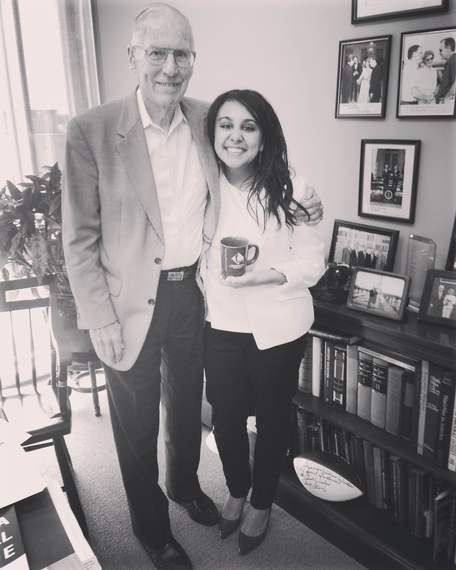

I had long known of his legacy, but I first, personally, met Governor Winter two years ago, shortly after I returned from graduate school to my home, Mississippi. I was (and still am) working for a state agency and spending a lot of time questioning whether working for the government was the best way I could influence change in Mississippi. You can only have so many conversations with yourself, and as a long-time admirer of his courageous story and consequential legacy, I one day decided to give Governor Winter's office a ring to see if he'd be willing to sit down for a conversation with me. To no surprise to those who know him, he asked if I was available the following week, and the rest, as they say, is history. That call led to a series of lunch and tea dates, rich with the Governor's sharp wit and humor, wisdom, and stories of inspiration.

Brief History of Governor Winter

Governor William Winter, 92 years young and with the vitality of someone 50 years his junior, was Mississippi's governor from 1980-1984. He twice lost the race for the governor's seat, before he won the third-time around. After his election, Governor Winter pushed for passage of the Mississippi Education Reform Act (MERA). It failed to pass three times. His supporters begged him to not try again, to not embarrass them. Despite this pressure, in December of 1982, Governor Winter called a fourth, special legislative session to push its passage. It passed. And, to this day, "the Christmas Miracle of 1982" remains Mississippi's most significant educational reform act.

He persisted through failure after failure after failure. And the outcome was one of the most impactful accomplishments Mississippi has ever borne.

Down in this part of the country, we say you're a blessed person when you encounter a person like William Winter. And, when you do, you know, because you hang on to every word uttered, silently hoping s/he doesn't stop speaking. And when s/he does, you quickly seek silence, refuge from the world's noise, to ask yourself the questions that inevitably arise from a conversation with a person like William Winter: "am I living right? Have I, thus far, committed my abilities to influencing the greatest good for the greatest number of people? Have I been too timid in my pursuit of justice? Have I been enough courageous? Have I been enough insistent and persistent in my convictions--despite the masses of opposition?" And, when you're asking these questions right after speaking to a person like William Winter, inevitably, your response is, "no, I have much work left to do."

Governor Winter's legacy is most strongly identified by his continued support of civil rights and equal opportunity for all, racial reconciliation, and most notably, passage of the Mississippi Education Reform Act of 1982. This act mandated kindergarten and school attendance for all students until age 18--all that more consequential for Mississippi's racial minorities as the state continued to resist desegregation. (Mississippi abolished mandatory school attendance after the Brown decision). But, those are just some of his more prominently discussed accomplishments.

Although he's quick to dismiss credit, Governor Winter helped catalyze existence of the Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science (MSMS)--a public, residential school for the state's academically gifted. MSMS was specifically created to provide a rigorous academic program and opportunity for students of diverse backgrounds, creating the next generation of Mississippi leaders. In a state where the public education system consistently ranks last and where 29% of the state's children live in poverty, MSMS is a beacon of opportunity to students--and it is a particularly powerful opportunity for those who live in economically and academically disadvantaged areas of the state.

As one indicator of MSMS's capacity to transform Mississippi students' lives, it was the first school in the state of Mississippi to break into the Daily Beast's rankings for best American high schools; last year, it was ranked the 57th best high school in the nation. Just last week, one of its alumni became the first black, woman Rhodes Scholar in Mississippi history. MSMS doesn't seem to believe in ceilings, because it consistently breaks through each one imposed upon it.

In 1981, Governor Winter toured the first math and science school in the nation, the North Carolina School for Science and Mathematics. The only other school in existence at the time was the Louisiana School for Math, Science, and Arts. Impressed, he brought the idea back to the Mississippi Legislature and several leaders across the state. At the time, Winter was fully engrossed in fighting for MERA's passage, so he was forced to plant the idea seed for MSMS and leave its fight for a later time. Shortly after Winter's tenure, Representative Charlie Capps presented legislation to establish MSMS--only the 4th school of its kind at the time (Illinois had established such a school only a few months before), and it was passed under the next governor's administration.

Although legislation for MSMS was not passed until 1987, MSMS was Governor Winter's brainchild. This past May, MSMS graduated its 25th cohort. That's 25 years of Mississippi students--many of whom would otherwise not have had a quality education, let alone enough tools to compete on national and international scales--who are indebted to Governor Winter for empowering them to leap over Mississippi's hurdles.

As a beneficiary of both MSMS and a racially integrated, public K-12 schooling, Governor Winter's fingerprints are all over my education. His legacy to me--education--will forever pay dividends in my life. Similarly, his life story inspires me toward a strong moral imperative.

Recently, a Mississippi grassroots coalition, 42 for Better Schools, lost a well-fought attempt to require state legislators to adequately fund Mississippi's public education system. Around the nation, we're seeing similar losses to healthcare access, religious bigotry, and income inequality chasms, to name a few. If Governor Winter's experience with loss and triumph stands to teach us anything, it's that the fight is not yet over. Governor Winter's journey to pass the Mississippi Education Reform Act, as well as his leadership experiences in some of Mississippi's most intensely, racially divided days, inspires us--near and far--toward the continued, good fight.

In one of his essays, Governor Winter states, "in our self-centered preoccupation with our own private interest, we tend to forget that we are bound together by a social contract that requires us to get along with each other and to look out for each other. We ignore the obligations of that contract at the risk of losing our souls." Through example, Governor Winter has deeply influenced how I, and many of my peers and predecessors, understand our commitment to the social contract.

Can you talk to me a little about pushing for education reform as governor?

We were confronted with a status quo legislature. A very conservative legislature, which has marked the history of legislative action in MS for as long as I can remember. It was a very conservative leadership that in the past had even opposed the building of a four-year medical school because first, it cost too much and second, it would lead to integration. So, even after we had gotten past most of the massive resistance to integration by the 1980s, there was still a lot of resistance to funding public schools. Because, it would primarily benefit black children.

We failed the first three sessions, under my governorship, to pass any meaningful education legislation. We were defeated, shot down three times-- in '80, '81, and '82. By that time, most of my supporters were disappointed in me, because I had not provided what they considered to be effective leadership in getting it done. There was a great deal of hopelessness about ever getting a progressive legislative program. That was when, after that third session, when we were defeated, that is when we really went to work. That's when we organized, county by county, and held public forums in ten different communities around the state, and tapped into that undetected and residual public opinion out there that wanted to see us succeed. And, then in September of 1982, we printed about 400 brochures to hand out at a public forum. There were 2,700 people who showed up at the first one in Oxford. I told Dick Molpus, who was with me that night, 'we've tapped into something.'

By the end of our ten sessions around the state, we had the attention of the legislature, and I decided to call a special session. But, there was still defeatism in the legislature. Even my strongest supporters argued against calling a special session, because they said all it would do is create embarrassment when it failed, when nothing happened. But I knew if we didn't do it in a special session, we wouldn't do it at all. I was a lame duck governor. I couldn't run for reelection; I only had one term. So, in mid-December, three weeks before the regular session was to convene in January, I called a special session, over the open protests of 90% of the legislature. That's when the people's voice was heard: the halls of the capital were filled with people who had driven in to personally confront their legislators. And in two weeks time, we were able to pass this massive education reform act and fund it with the largest tax increase in the history of the state.

It was called the Christmas Miracle of 1982, and I still read about it and wonder how we did it. But we did it, because we developed massive public support, which was waiting for someone to come along and mobilize in a way that would result in legislative action. And I had several members of the legislature come up to me after it had passed to say, 'I never would have believed I would have ever voted for something I was once so strongly against.' But that's how it was done, and it's still a marvel, I think.

How did you stay hopeful when you didn't have political support?

I found, literally, so much inspiration in some of the young people with whom I was working--I was in my 50s, they were in their 20s--who insisted that we make these things happen. If I had surrounded myself with my own contemporaries, so many of whom were almost indifferent or even hostile to the changes being suggested, I would not have found the inspiration and the source of strength that these young people permitted. They came along and wouldn't let the rest of us quit.

On the Education Reform Act, when I was governor, I must tell you, I was ready to throw in the towel. Summer of 1982, I had almost given up, and I was ready to let someone else have it. When I would talk to the boys of spring--Andy Mullins and Dick Molpus and Ray Maybus and folks like that--they would say, 'no, we cant quit! We're too close. We're going to have one more shot at it.' And that's where I learned that persistence was maybe more important than anything else. That if you just hang in there long enough, you're finally going to break through. If you're on the right side, you're finally going to break through. And that's what happened in 1982. When I called that special session, nobody, literally, nobody, thought the legislature would respond. The legislators themselves thought they wouldn't respond. They pleaded with me not to embarrass them by bringing them to Jackson. But it was the darkness just before dawn and the sun was just beginning to come up.

MSMS is extremely near and dear to my heart. Right up there near the value I give to my faith and family. I know you didn't sign that bill, but it was your idea. I could write you a book full of stories of the number of people I know whose lives are forever changed because of MSMS. It's an exemplary school, period, but it's even more life changing for students who live in communities with poor school systems, who don't have the funds to enroll in a private alternative.

That just makes me so delighted to hear. That I was able to contribute to something so remarkable for the state of Mississippi. I'm proud of that. And all those students with that great education, coming back home to contribute to their home state in some way, that just makes me so happy. MSMS sets the standard for the rest of our schools, to aspire to its level of excellence.

One lesson I take from your involvement with MSMS's creation is the importance of going out there and learning about what's going on in other communities and bringing the ideas back to the people. Because that's what started MSMS.

Yes, exactly. You plant these little seeds out there and hope that some of them will sprout.

I returned to Mississippi, because I had a flaming desire to impact the root, social and political, determinants of public health disparities. When I came back, the major health battle regarded health care access. Medicaid expansion in Mississippi would have brought access to over 300,000 people in this rural and poor state. If any state was to benefit from Medicaid expansion, Mississippi topped the list. But as a recent article detailed, all efforts to push for Medicaid expansion and/or run our own state-based marketplace exchange were viciously fought against. In the end, the people lost and State Leadership obstructed 300,000 people from a powerful means to protect their health. Fiscally and physically, it would have benefitted Mississippi; so, watching this battle be fought over ideology and not facts was painful. Understanding this current, political environment, would you encourage a young professional to invest her/his youth in Mississippi?

Oh, I'm going to love talking to you about this. I always come back to this point. There are more opportunities in a state like Mississippi to make for meaningful change on an individual basis than there is in almost anywhere else in the country. We're still a community where people know each other, and there's still a sense of group responsibility.

I've found so much fulfillment in working through the things we're confronted with. I can't explain to you what it was like to have progressive ideas in Mississippi in the 1950s. Everything was measured in how we maintained racist segregation. Any change that would seem to weaken our position on segregation would fail. And that's why we can consistently turn down federal money for education. This is why we resisted building the Veteran Administration Hospital, because it would lead to integrated wards, even though the governor at the time was a veteran, himself. That's the mindset we run into and are confronted with and are frustrated with, but I have seen so much change take place because of the anger and efforts of the individuals like you who are committed to make things happen.

I don't need to tell you this, you know this a lot better than I do, but one of our failures is to produce the atmosphere where people understand what good health is all about. I'm expressing frustration at the same time I'm expressing a great sense of opportunity. Those are my words that will hopefully help encourage you not to give in to the misgivings about the future. I think the future in this state is very bright. And in a short period of time, I think we will see a major breakthrough in our health care system.

I wonder how many legislators actually agree with Medicaid expansion, but don't dare speak up in this political climate.

At a luncheon in her honor, I said to Myrlie Evers, Mrs. Medgar Evers, 'we white folks owe as much to you and your husband as black folks do, because you freed us, too. We white folks were prisoners of a system, an indefensible system that we insisted on defending, and I was not free to say what I thought. I was intimidated as much as black folks were.' We in the past have had that total intimidation that kept us from doing and saying the things that we thought we should do and say. The same thing now, as you pointed out, so many legislators feel intimidated.

Speaking of race, racism is being confronted head on in Ferguson, Baltimore, and increasingly more cities and universities across the country. From your experience during segregation, during the fight for desegregation, and from serving on President Clinton's Advisory Board on Race, does Mississippi have anything to teach other states?

Absolutely! We have a lot to teach them. 40 years ago, we were where Baltimore is now. We had declared war on ourselves. At a time when other cities were sweeping their problems under the rug, we were actually dealing with them in the rawest confrontations. And so the battles we fought in the '60s, I think, prepared us to develop a relationship, here, that has been much more hopeful, much more real, much more constructive than the folks in Baltimore have had.

Yet, I also understand that we have some of the same problems that they have in Baltimore. People all over have refused to face the reality that there is a simmering problem that would not go away and had to be addressed and so we have seen this rise in the last few months. I saw it with the Clinton Advisory Board. We had some very, very candid, heated, hostile conversations in places far removed from the south. In LA, for example, when the riots started over Rodney King. We met with the people in those communities, and we saw there was this deep-seated lack of trust that boiled over in the riots of the '90s.

Addressing racism is both an individual and national priority. People must recognize their individual responsibility to develop a more united society, and a lot of people don't want to do that. They don't think it's necessary. You can find Fergusons all over the country. You don't have to walk too far to find a Ferguson or Baltimore around here. And this is what the Winter Institute here in Mississippi is all about. It is creating, community by community, an understanding of what true racial reconciliation is, instead of running away from it. So, this must have a national sense of priority, because it's a national problem.

What do you see as the most pressing issue for Mississippians?

The one thing we can do, that I believe can make a greater difference than anything else, will be a statewide, comprehensive, well-funded, well-administered system of pre-k in every school. If I had to put my finger on one thing I think we could do now that would make more difference than any other single thing it would be a coming together, a true coming together, biracial, multiracial, coming together to create an education system that uses all of the resources that we can bring to bear--financial resources and intellectual resources--in ensuring every future child born in Mississippi, black or white, poor or not, has a support system out there. We must see to it they are intellectually, physically, culturally prepared to develop themselves as fully as they can. We will never solve the dropout rate until we put more attention to develop the minds of these kids, these babies that come along without a strong support system. We will never achieve our competitive capacity. I just believe that so deeply.

And this problem is more acute in a state like Mississippi where we have a high percentage of people coming along without the resources, the domestic/home resources that permit them to advance. So, generation after generation, we have the have-nots continuing to be the have-nots. Money alone won't do it but school improvement can't be done without money. We will eventually overcome these deficiencies, but we're losing an awfully lot of young people in the meantime.

Mississippi, in the national conversation, is often ridiculed. A lot of us want to change perceptions, encourage people to give Mississippi a chance, visit, and contribute to Her success. What are your suggestions for how we can help change these perceptions? Is there any message you'd like to give a national audience?

Pursue more aggressively the dissemination of helpful information of what's going on in Mississippi. The article that you've been working on, let that be a message sent out across the country. Those stereotypes die hard. People assume nothing changed and nothing will change. We have to have cheerleaders. But not in a sense of making everyone feel good, but cheerleading in a sense of showing people what we are accomplishing. The critics and the cynics leave no monuments, they leave only ruins. When we set our standards high, we pull up to those standards.

Mississippi is different. It is uniquely different. It is a state, which by virtue of its conflicts over the years, its defeats and victories over the years, nothing has come easy for Mississippi. We have had to overcome wars and ignorance and politics of cruelty. We're still getting over the civil war. But because of these conflicted experiences that we have had, Mississippi really is a social and economic laboratory with a mystique about our culture and our history. And it's not all good. A lot that we're not proud of. But because of the conflicts and the battles we've had to fight over the years just to survive, we're the kind of state that can provide lessons in how to overcome the difficulties that we've had.

We haven't been spoon-fed, we've had to battle for just about everything. We've wounded ourselves in so many ways, been our own worst enemies. But in the same time, in the struggle to survive, it has created within our identity a toughness and a resolution to build a successful community. I know I feel deep within me a satisfaction in seeing what so many of my contemporaries, my fellow citizens, have been able to do, overcoming their past to become productive citizens, committed to building better communities. If we can market that as one of our characteristics--of understanding what we have been able to overcome and what we have been able to accomplish, to make up for the mistakes we've made. We have a sense of who we are that a lot of other people don't have. That's why I recommend folks raise their families in Mississippi.

What is the solution to what seems like mass apathy and ignorance?

It's a real paradox, because technologically we are now able to communicate with nearly everybody in the world almost instantaneously. Yet, I think there's more confusion about wise political decisions than there's ever been. Because the process of communication is now open to everybody, we let the negative forces and the cynical forces dominate the conversation. Right wing radio shows and television and the internet are influencing more people than the more reasonable positions. There is no simple answer to that except the commitment of enough of us who I think are committed to doing that which is in the best interest of this country.

What advice would you give people my age who are on the search for meaningful work?

Maintain a resolute commitment to using your talent and opportunity to solve the social and political and economic problems that we have always been confronted with, but now seem to be so much more complex than they have been in the past.

And the advice that I would give above all other things is let us not fall into an attitude of cynicism or negativism or indifference in approaching these issues. One of the things we tended to do in the past is, when we reach a point where there does not seem to be an acceptable solution out there, we sort of kick the can and hope opportunities in the future will be better when the civic and political atmosphere can be dealt with. Right now, there's such a negative attitude about whether the political system is capable of making the decisions that must be made, so there's kinda this continuing deadlock that even those in power to make decisions just kinda throw in the towel. The message is it's more important now than it ever has been, particularly for young people, to put their best and strongest efforts into whatever process is going to lead to ultimate solutions for these problems.

And it is so naïve to think these problems are going to be solved quickly or easily, but let us at least not stop working. The ultimate message is don't give up, hang in there. Back in the '60s and the '50s, my contemporaries said, "what's the use, we'll never overcome segregation, we'll never overcome Jim Crow. So, what's the use? Let's go somewhere else. Let's go do something else." We finally solved what was seen as an insoluble problem, and we changed public opinion.

What's one interesting thing about you or your life that most people don't know?

Without being flippant in my response, what most people don't know is I still feel like I'm a little boy. I really try to preserve that wonder at living as I grow older. Just a wonderment about living that I have always taken for granted, but now as old as I am I recognize it is what has kept me living--and that is the wonderment that has kept me associated with all the people and experiences and memories. I literally get up every morning just thinking what a lucky person I am to get up and get out and take my dog walking and have a conversation with my dog. He and I talk all the time.

Governor, you have more stamina than me with pots of caffeine, sweet tea and hot tea, in my system. At the age of 92, how do you still maintain this energy?

I would have been long since in the cemetery if I just retired when I got to be 65 or 70 years old and just went home. I get so much stimulation when I think, and it enhances my physical capacity. Out of doing things that are meaningful to me, not taking myself too seriously, but saying this is my town, this is my city, this is my state, this is my country. Doing what I think is important, whether anyone else thinks it's important or not.

***

In a documentary on his life and career, William Winter's Mississippi, the Governor succinctly sums what I cannot stop hearing and what may best capture the lesson he has imparted upon the generation, my generation, obligated with carrying forward the torch of justice in the march our forefathers and foremothers began for us:

"There are times when you just have to stand up and say this is what I'm gonna do, and we won't worry about how it comes out."

***