This is the third installment of a four-part series chronicling singer-songwriter and producer Shawn Amos' childhood in 1970s Los Angeles. Read second installment here.

At the Ralph's supermarket on Sunset Boulevard, Wally was inexplicably drawn to Aisle 14: kitchenware, plastic bags, spices and flavorings, desserts, baking needs. Dubbed the "Rock and Roll" Ralph's by locals, the 24-hour market served a cross-section of Hollywood low life. On any given night, stoned musicians with the munchies stood in the check out line with Red Vines and Cheez Whiz next to homeless dudes spending hard scrounged change on a 40 ounce of malt liquor. Wally stopped at Ralph's many nights on his way home and he shopped like most single guys: for food that could be eaten with little more effort than opening a can, removing a lid, or tearing a wrapper. This usually kept his grocery store trips limited to the produce section, frozen food, and breakfast aisles. But on this night, Wally was looking for comfort food. He found it in four words written on the front of a cellophane package: Nestle Semi-Sweet Morsels.

Morsel is a perfect word. Forming those six letters on the lips and tongue prompts an instantaneous physiological reaction. The mouth waters. The lips purse. Morsel: there's a bit of desperation in the word. A wanting. Now add the word "semi-sweet" in front of it. "Semi-Sweet Morsels." Not sickly sweet so you need a glass of water afterwords to avoid a stomachache. Semi-sweet. There's almost a sadness. A melancholy either caused or cured by that morsel.

The package was yellow. That kind of yellow that kindergartners mistake for the color of the sun. The yellow on your first watercolor painting. The one with the rectangle smear of green paint sitting below a bright red box underneath a brown triangle. Two stick figures standing stiffly inside the box. Crammed next to one another, the ends of their stick arms almost touching where their phantom hands should be. Above the house is a manic blue sky, painted in swirls and splotches. Some of the sky has dripped onto the roof of the house. And pushing itself into the upper right corner of the construction paper is a sun. The weight of its color is almost too much for the paper to hold. It buckles under its density, a wave of retina-burning optimism with exactly five rays racing from its center. Five lines straighter and more exact than anything else on the page. A perfect circular yellow, two-dimensional ball that can only be stared at safely in the corner of a kindergarten watercolor.

The package of semi-sweet morsels was the size of a brick. There were at least twenty packages stacked on one another, on the top shelf of Aisle 14 at the Rock 'n' Roll Ralph's. Wally had never been on Aisle 14. It was midnight at the Rock 'n' Roll Ralph's. Wally stared. To the right of the words "Semi-Sweet Morsels" a piece of the yellow was burned away revealing the contents of the package through a two square-inch window. Behind it, an impenetrable wall of chocolate chips. Hundreds of them. Wally massaged the package in his hand, feeling the chips inside fall over one another. He looked through the window again. It was his Aunt Della's window. Wally remembered standing on that apple crate in his Aunt Della's Harlem kitchen. Handing her that wooden spoon to mix the batter. Wally remembered Aunt Della's Harlem home. He missed home. Wally grabbed one of those yellow, cellophane bricks. He didn't quite know why.

On the back of the package, Wally saw directions: "Toll House Cookie Recipe." Ruth Wakeman owned the Toll House Inn, a popular 1930s restaurant in Whitman, Massachusetts. She made home cooked meals and gave her customers an extra helping to take home. Aunt Della probably knew about Ruth Wakeman. Wakeman is credited with making the world's first chocolate chip cookie when in 1934 she ran out of usual baker's chocolate and was forced to use Nestle semi-sweet chocolate in her cookies. Wally read the Toll House recipe. He walked up and down Aisle 14 putting the spices and flavorings and baking needs in his cart. Then he left the Rock 'n' Roll Ralph's and headed home.

Lots of people had the munchies in 1970s Hollywood. At every sound stage, recording studio, and talent agent conference room, someone was certain to be high and hungry. Wally's cookies were the perfect opener to every pitch meeting, every break in production. There was nothing in Wally's cookies other than his own variation of Ruth Wakeman's ingredients. He liked adding more chocolate that Wakeman called for. He added some coconut which was not listed on the Nestle package. Wakeman's recipe simply asked for "chopped nuts." Wally chose pecans, maybe an ode to his Southern roots.

Wally's cookies became his calling card. Literally. Everywhere he went, he carried a plain brown paper bag with him. A chocolate chip pusher to a cotton-mouthed town. His cookies were a testament to the power of home made creation. Each one mapped with a unique DNA sparked when Wally's hands pinched off a piece of batter with his fingers and placed it onto a 99 cent cookie sheet. They were golden brown, a mixture of sunshine and caramel -- almost shiny with an uneven surface of pecan peaks and melted chocolate valleys. Wally's cookie were crunchy -- at first resisting an initial bite. Once the teeth did penetrate, they were rewarded with a coating of chocolate across the front. From here the tongue took over, distributing the chocolate, crumbs, pecans, and coconut into the left and right cheeks. Soon the entire mouth was transformed into a mixing bowl filled with a rich cookie batter. Swallowing came too fast and was immediately followed by another silver dollar sized cookie being popped into the mouth. It was instinctive, reflexive, and compulsive.

Wally's cookies were bite-sized flashbacks turning grown men and women into four-year-old kids begging their parent for another lick of the spoonful of batter. Whenever Wally held open his bag to a friend or business associate, the script was always the same:

"Thanks, Wally, I'll just have one."

[grabs two]

(Mouth full) "Man, these are good."

(Chewing) "Okay one more."

[grabs three]

"You got any milk?"

[grabs two more]

"OK, that's it."

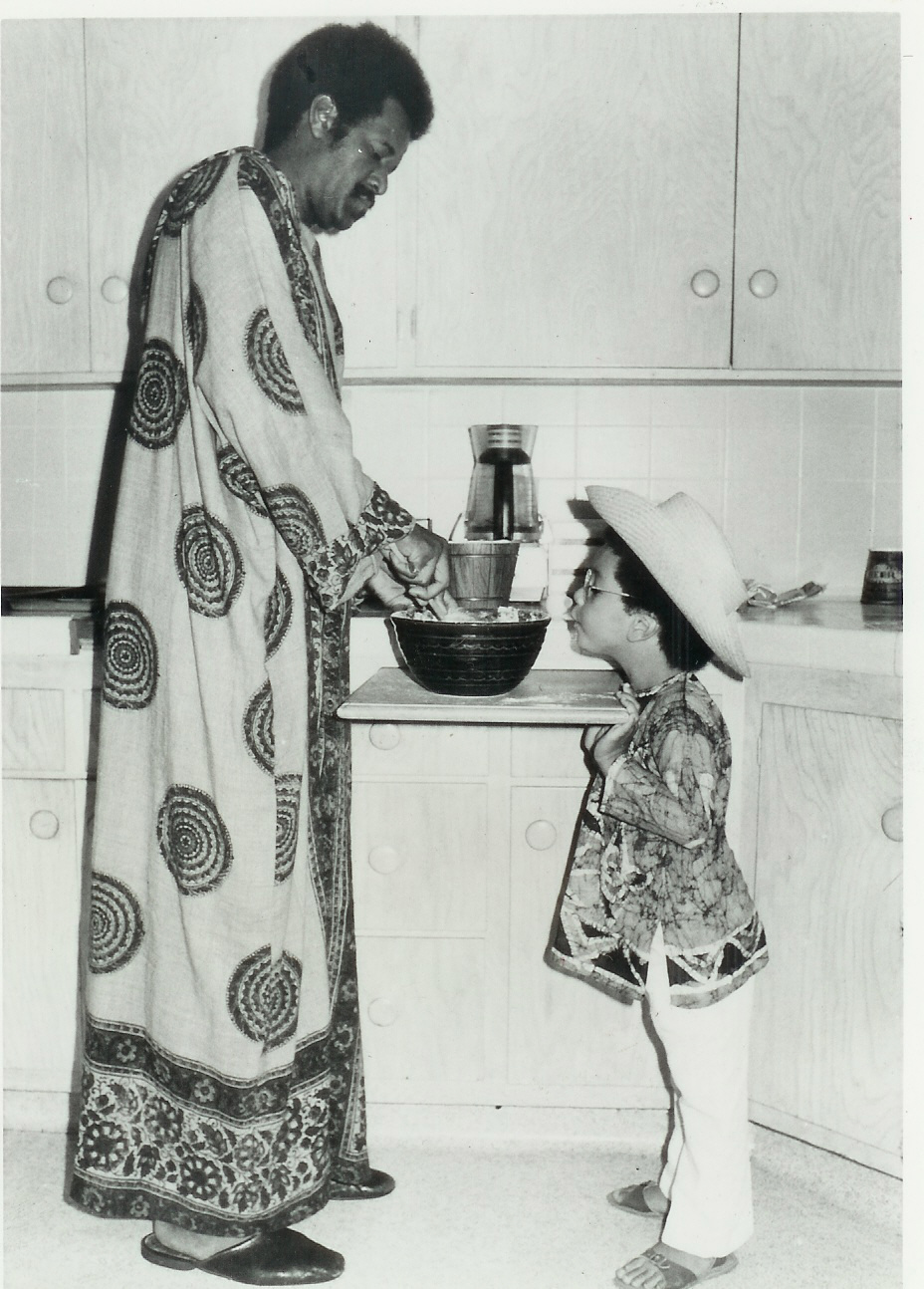

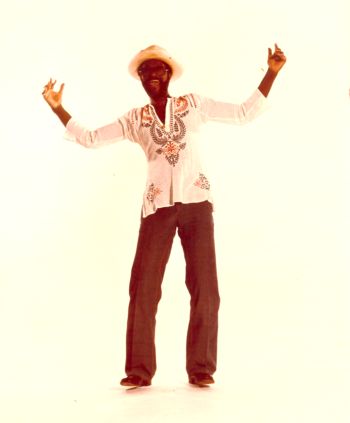

At night, Wally would tinker with his recipe, wearing an African robe that was de rigueur for a certain kind of hip '70s black male. He was Ruth Wakeman in a dashiki. The intensity on his face belied the joy in his heart. Wally was lost in his kitchen. It was his escape and his salvation. It was his therapy. It was also the start of his biggest hustle.

At A&M Records, Wally's cookies were in constant demand. He was holding onto an office on the second floor of a two story bungalow on the south side of the lot. In the building to the right was Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss' single-story bungalow. I began a habit of greeting Herb on days when I visited A&M. From the balcony above, I'd call out, "Hi, Herbie, baby." I had heard Jerry and others call him "Herbie" and the name was hysterical in my six-year old mind. Herb tolerated me. The whole lot tolerated me. It was one of my earliest playgrounds. Quincy Jones had an office down the hall from Wally's. A large sign of his recently released album Body Heat album cover hung on the wall outside of the building housing A&M's recording studios. I became Wally's messenger, a job I relished. Secretaries would greet me and my small bag of cookies. My delivery would gain me entry into vocal booths, conference rooms, and Herbie baby's office. Wally's cookies introduced me to an adoptive family of surrogate mothers and fathers who all took me under their wing -- at least until the cookies ran out.

On the A&M lot, Wally's cookies were a bigger conversation than his clients. People were slowly forgetting about Franklin Ajaye and "Mississippi" Charles Bevel, but they wanted to know when they could get another brown bag delivered to them. Wally was spending more time at night in the kitchen than comedy clubs or sound stages. When Wally did go out, he was shopping himself and his cookies more than shopping for his next client. He was building his fan base. Wally knew he didn't want another client. He was done with singers who got cold feet and comedians in the right place at the wrong time. Wally's entire life was tied to others who held his fate in their hands. His life was not his own. Seven years ago he had moved his family to Hollywood, hitching his future to one South African trumpeter who dumped him as soon as he crossed into the California border. Ever since, his life had been one endless loop of courtship and breakup.

People greeted Wally's cookies with greater enthusiasm than any client he ever had. They understood Wally's cookies better than they ever understood the Frankin Ajaye jokes about high school bully Bumpy Woods or the Mississippi singer who kinda sounded like Cat Stevens. Wally's cookies were colorblind in a way that his black artists were not. Plus, cookies couldn't talk back or break a contract. They were the perfect client, and they were doing something no other client had ever done: making Wally famous.

Final installment: March 1

Shawn Amos is a singer-songwriter, producer and founder of digital media company Amos Content Group. His album, Harlem is being released today.