The Getty Research Institute's special exhibition The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals offers opportunities to travel through time and learn about culinary theatrics from the past.

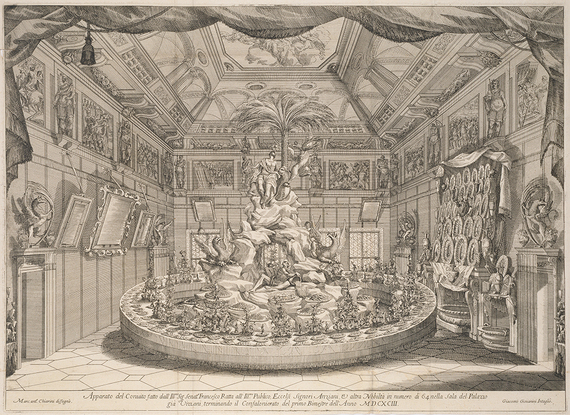

In early modern Europe, food was spectacle. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, ostentatious court and civic banquets were de rigueur, and illustrations of these feasts endure in the books and prints designed for the Italian and French courts. Of course, the production of such lavish spectacles required a cook and a kitchen brigade. The early concept of the "celebrity chef" emerged in the late 16th century; by the 17th century, chefs were revered.

Centerpiece for the feast of Senator Francesco Ratta, Giacomo-Maria Giovannini after Marc'Antonio Chiarini, 1693. From Disegni del convito fatto dall'illustrissimo signor senatore Francesco Ratta (Bologna, 1693), frontispiece. 1366-803.

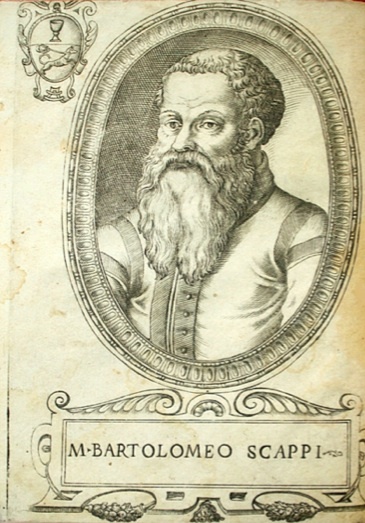

One of the first chefs to put culinary innovations in writing was Bartolomeo Scappi in his monumental Opera dell'arte del cucinare (Works on the Art of Cooking), of 1570. The Joy of Cooking for the Italian Renaissance, Opera is divided into six books covering everything from choosing staff and stocking the kitchen to cooking for the infirm, with over one thousand recipes for meats, fish, vegetables, desserts, and sauces in between. It also illustrates how, by the 16th century, kitchens had become a complex series of spaces dedicated to different operations. Organization was critical when banquets lasted for hours -- sometimes days -- with thousands of mouths to feed and eyes to delight.

Portrait, Anonymous. Engraving, Bartolomeo Scappi, Opera de M. Bartolomeo Scappi, cuoco secreto de Papa Pio Quinto (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, [1570]), p. 1.

Catherine de Medici proudly owned a copy of Scappi's Opera and brought it with her to France. And it was the French -- with their creamy, elegant sauces -- who developed the extravagance and showmanship that every European court strove to emulate. During Louis XIV's reign (1643-1715), classic French haute cuisine was born. Great chefs wrote treatises on the arts of carving and serving, as well as the complexities of gastronomic etiquette.

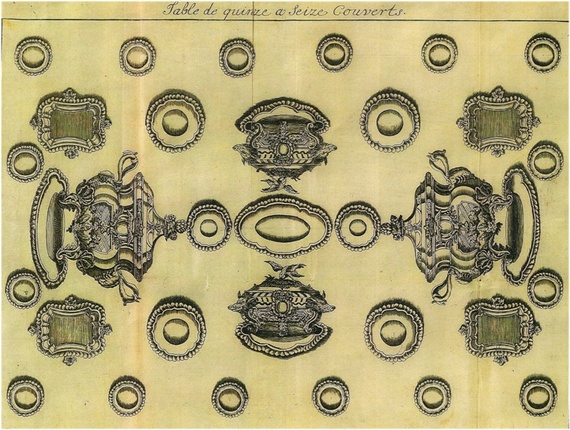

Chef François Pierre La Varenne was the first to put these innovations in writing in his 1651 cookbook Le Cuisinier françois (The French Cook). At the end of the century, François Maissialot introduced his famous Le Cuisinier roïal et bourgeois (The Court and Country Cook), with folding plates devoted to table settings.

By the time of Louis XV (1710-1774, reigned from 1723), French cookbooks had become grand productions. The most spectacular was Vincent La Chapelle's Le Cuisinier moderne (The Modern Cook) of 1742 -- five volumes with thirteen folding plates, one of which measured over three feet when fully open and depicted a table setting for one hundred guests. La Chapelle's book announced the birth of nouvelle cuisine, a new style of cooking that would be adopted by several generations of French chefs. Luxury ware for the dining room went hand in hand with these theatrical culinary innovations.

The dessert table didn't go unnoticed. By the 18th century, sugar was an important expression of power. Sugar held an exotic allure in Europe until the 12th century when Arabs started cultivating it in Sicily and Spain; it began to rival honey as the sweetener of choice in Europe.

The discovery of the New World in the 15th century led to greater sugar cane cultivation - first in the Caribbean, Brazil, and Mexico, then in the islands off the Indian Ocean and in the Philippines. The growing European demand for sugar -- heightened by the fashion for sweetened tea, coffee, and chocolate - -was a major driver of the slave trade.

Of course, French aristocrats weren't thinking about this issue when decorating their elaborate dessert tables with all sorts of sweets and dainty, sentimental sculptures made of the luxurious ingredient. After the feast, these sugar sculptures -- called subtleties -- were gifted as party favors.

(Juan de la Mata in particular, the dessert chef to Philip V and Ferdinand VI of Spain, was known for his over-the-top dessert spreads, which featured flowers, subtleties, and even fountains of milk or wine. His Arte de repostería (Art of Pastry) of 1747 includes all sorts of sweets, pastries, jams, cakes, meringues, doughnuts, and chocolates.)

Table with One Hundred Place Settings, Anonymous, etching, Juan de la Mata,

Arte de repostería (Madrid: Antonio Marin, 1747), pl. 10

The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals is on view through March 13, 2016. Do not miss it! Now here is a recipe of which Louis XIV would have approved, and a vegetable side with a good story to tell at your upcoming Thanksgiving feast, or for any feast!

Grilled Cauliflower With Lemon And Thyme

Cauliflower was introduced to France from Genoa in the 16th century and, though rare in French cooking, held an honorable place in gardens because of its beauty and delicacy. The gardener and scientist Olivier de Serres wrote about cauliflower in his 1600 book, Le Théàter de l'agriculture (The theater of Agriculture) and it is featured in La Varenne's Le cuisinier francois (The French Cook). Cauliflower's popularity grew when the its biggest fan, Louis XIV, demanded it be served on the grand banquet tables of Versailles.

1 large head cauliflower

½ stick butter, diced

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 tablespoon Dijon mustard

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1 tablespoon chopped fresh thyme

zest of one lemon

salt and pepper

1. Prepare the lemon thyme sauce. Combine the butter, shallots, olive oil, Dijon mustard, lemon juice and lemon zest in a medium saucepan. Whisk over medium heat until the butter melts and the sauce is well blended. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

2. Remove the leaves and trim the stem of the cauliflower, leaving the core intact. Place the cauliflower, core side down, on a work surface. Starting at the middle of the cauliflower, slice from top to bottom into four half-inch "steaks," reserving any florets that break loose.

3. Prepare a grill for medium-high heat and lightly oil the grate. Brush the cauliflower steaks on both sides with the lemon thyme sauce and season with salt and pepper. Grill until tender and charred in spots, about 5 minutes per side. (You can also brush them with the sauce and roast them for at 425° F for about 25 minutes.)

4. Transfer the vegetables to a platter, garnish with thyme sprigs, and serve.

Serves 4

cauliflower image by Maite Gomez-Rejon