Excerpted with permission from The Rise of the Creative Class Revisited: 10th Anniversary Edition, by Richard Florida. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright (C) 2012.

Someone recently said, "the longer the crisis goes on, the smaller the ideas for fixing it get." While pundits and commentators on the left and right savage each other over short-term fixes -- tax cuts versus stimulus, budget cuts versus monetary easing (I could go on) -- our economy is still sputtering and Europe is teetering on the brink of economic collapse.

Policy-makers and central bankers have been able to stave off the massive economic dislocation brought on by previous crises like the Great Depression of the 1930s or the Panic and Long Depression of the late nineteenth century, but what we are going through is not any run-of-the-mill economic cycle. It's an enormous structural transformation -- similar if not larger in scale and scope to the shift from the Agricultural to the Industrial Age.

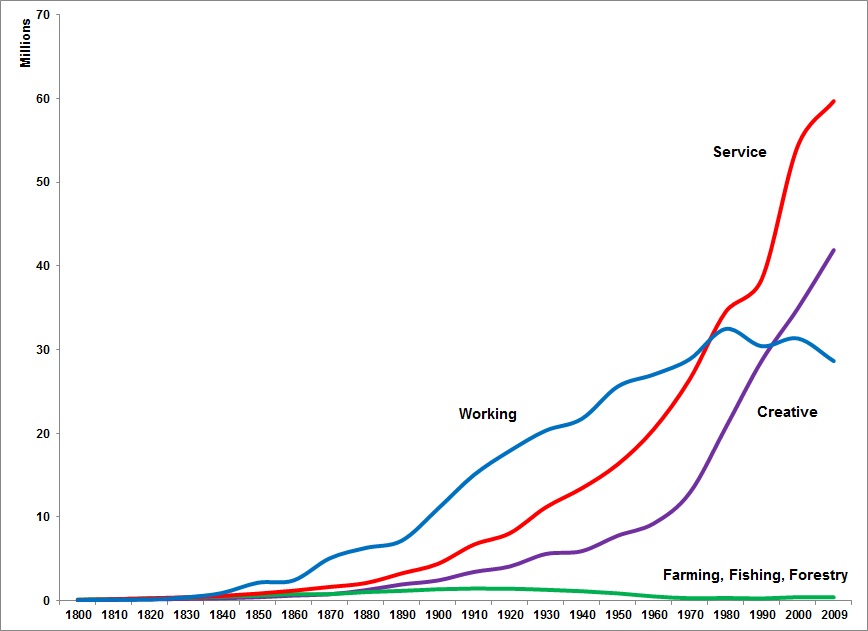

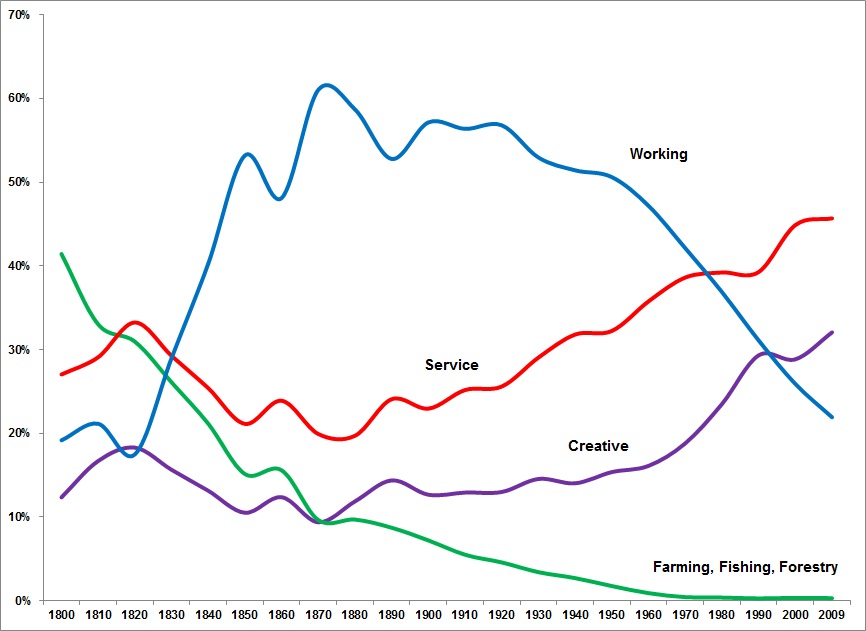

Two charts make this abundantly clear. The first one (above) tracks Americans' employment from 1800 to 2010, across the nation's three great economic eras -- the Agricultural Age running from the time of Western settlement until the early to mid nineteenth century, the Industrial Age from the middle of the nineteenth century until the middle of the twentieth, and the new Creative Age, from the mid-twentieth century to the present. The second chart (below) shows the same trends, but this time as shares of the workforce.

America came into being during the Agricultural Age. In 1800, four in ten Americans held jobs in agriculture. This declined to about 20 percent by the middle of the nineteenth century and to roughly ten percent by the turn of the twentieth century. By the 1930s and 1940s, it had fallen to about five percent. It is less than one percent today.

The Industrial Age saw the United States rise to economic preemince. The share of the Working Class or what Marx dubbed "the proletariat" surged to more than sixty percent of the US workforce in the 1880s and it didn't fall below 50 percent until the years immediately following World War II, when it began to decline steadily, falling to forty percent in 1970, thirty percent by 1990, and roughly twenty percent today. These blue-collar Working Class jobs include all blue-collar physical work, including construction, transportation and maintenance. Workers who directly produce things in factories account for just six percent of the workforce and are expected to decline even further over the next decade to around five percent, roughly equivalent to the level of Agricultural jobs during the last great crisis of the 1930s.

It's common to say we are now living in a post-industrial information or knowledge economy. But the shift is actually deeper and more thorough-going than that. Marx said that what made the proletariat a universal and indeed revolutionary force was the fact that they shared a fundamental bond -- the common physical labor that built bridges, buildings, railways, automobiles, and the like. But creativity makes for an even deeper bond. It is visible in every child. It is what distinguishes human beings from animals.

In his landmark book on economic progress from classical antiquity to the present, The Lever of Riches, the great economic historian Joel Mokyr distinguishes homo economicus, "who makes the most of what nature permits him to have" from the Promethean homo creativus, who "rebels against nature's dictates." And now creativity, "the ability to create meaningful new forms," as The Random House Webster's Dictionary puts it--has become both the driving force of economic progress and the decisive source of competitive advantage.

The Creative Age has been distinguished by the rise of two great social classes. The first is the Creative Class, workers in science and technology, arts, culture and entertainment, healthcare, law and management, whose occupations are based on mental or creative labor. The second and larger one is the Service Class, whose members prepare and serve food, carry out routine clerical and administrative tasks, provide home and personal health assistance, do janitorial work, and the like. The Service Class has grown alongside the Creative Class, rising from twenty percent of the workforce in the late nineteenth century and thirty percent in the 1950s to almost half of the workforce, 60 million plus workers, today.

The Creative Class, which comprised less than ten percent of the workforce in the late nineteenth century and no more than 15 percent for much of the twentieth, began to surge in the 1980s. Since that time more than twenty million new Creative Class jobs were created in the United States. This epoch-defining class now numbers more than forty million workers, a third of the workforce, and it generates more than $2 trillion in wages and salaries--more than two thirds of the total US payroll. An additional seven million or so Creative Class jobs will be created over the next decade, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics projections. Members of the Creative Class engage in complex problem solving that involves a great deal of independent judgment and requires high levels of education. Interestingly enough, however, the Creative Class is not simply another name for the college educated. While nearly three quarters of college graduates belong to the Creative Class, four in ten of its members do not have college degrees, but still engage in work that is creative by definition.

At the worst of the crisis, in the first half of 2009, the rate of unemployment for the Creative Class barely topped five percent, even as the rate of unemployment for the nation crested over ten percent and the unemployment rate for blue-collar production workers surged above 15 percent or more. Creative Class unemployment is roughly four percent today, a little less than half the rate for the nation as a whole.

Before we can fully recover from the crisis we need to implement new strategies that will speed the transition to the Creative Age. We must remove the central props that are holding up the old economic order--the incentives and subsidies that keep the badly broken housing-auto-energy complex breathing--and invest in the new economic order, smoothing the path to its transition by bringing more workers and Americans into its orbit.

The Creative Class itself is doing fine; its members average $70,000 plus in wages. The bigger task is both to add to and improve the remaining two-thirds of jobs. The only way to do this is to essentially creatify them. It's happening already in advanced manufacturing plants that no longer view workers solely as a source of brute physical labor but as members of innovating, knowledge-generating and problem-solving teams. We must do for Service work what we once did for manufacturing.

While we sometimes forget this, the blue-collar jobs that we so pine for today weren't always good family supporting jobs. William Blake aptly dubbed factories "Satanic mills," and for much of the Industrial Age, the work was low-pay, dirty and dangerous -- what Marx said would lead the proletariat to revolt. We established a new social compact during the New Deal and post World War II era that turned these formerly bad jobs into good ones.

My own father, who began work in a factory at age thirteen in the middle of the Depression, often recounted how during that time it took nine family members -- his mom and dad, himself and six siblings -- to make a single family wage. But when he returned from World War II and went back to work in the very same factory, his wages had grown to the point that he could buy a house, have a family and eventually to put his two boys, my brother and me, through college. Some of this was because of collective bargaining, some of it was because of increased productivity.

We can do the same for the tens of millions of workers who toil in low-wage service work today. My own research shows that adding creative skills to service and manufacturing work boosts wages at an even higher rate than it does when it's added to knowledge work. Upgrading service work is not only good for Service Class workers, it can provide a much needed boost to the economy, increasing productivity and purchasing power and stimulating demand (as was the case with higher-paying blue-collar jobs in the 1950s and 1960s).

Yes, we will all have to share the cost of higher-paid service work, just as we paid more for cars and manufactured goods after World War II. But think about it this way. What would you rather pay a little more for? The workers who make your car, washing machine or refrigerator, or those who prepare your food and take care of your kids and aging parents? The burden of renewed prosperity is one we all have to share.

To get there, we need a new social compact, one that is similar, though by no means identical, to what unions and the New Deal accomplished. But this new social compact must be fundamentally in sync with the demands of the new Creative Age. To that end, it must invest in our most important economic asset--the creativity of every single citizen and human being--in order to upgrade and generate new higher-paying jobs, address the gross inequities in our economy and society, and lay the institutional foundations for a new era of shared prosperity.

My next post will outline the key elements and underpinnings of this new Creative Compact.

This article draws from material in chapter three of The Rise of the Creative Class Revisited to be released by Basic Books on June 26th. Richard Florida is a professor at the University of Toronto and NYU and senior editor of The Atlantic.