The city of San Diego lies just minutes away from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Nicknamed "America's Finest City," California's southern-most city boasts a mild temperate climate which attracts tourists year-round. San Diego also has the third-lowest crime rate among all large cities in the country.

Yet just 10 miles away, on the other side of the U.S.-Mexico border and well within sight of America's Finest City, there exists a potential humanitarian crises of significant proportions.

El Bordo

Within Baja California's largest city of Tijuana, which similar to San Diego has a population of over 1.3 million people, exists a dry concrete riverbed that once held the flowing waters of the Tijuana River. What has replaced the river is a massive influx of more than 4,000 deportees from the United States, most of them men with very limited resources who now call this region of Mexico's border city their home.

Locals call this large concrete embankment "El Bordo" which roughly translates to "the border," or in more informal terms, "the ditch" given Tijuana's location on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Everard Meade, the director of the Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego, studies the relationship between the San Diego and Tijuana communities.

Meade said that the majority of El Bordo's residents are from other places in Mexico. Most of them have connections in the U.S., including family and job prospects, and hope to return to the country.

"They stay in the border towns because they have aspirations of returning to the U.S. to be reunited with their families," Meade said. "That's really hard to do though."

Meade attributed the large homeless population to the record number of deportations President Barack Obama has issued during his presidency. Since Obama took office in 2009, his administration deported approximately 2,000,000 people, the most ever recorded for a U.S. president. Approximately 40 percent of the deportations took place at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, the world's busiest border crossing connecting San Diego and Tijuana. That translates to approximately 800,000 people deported from the U.S. to Tijuana.

"When they're deported, their personal property is seized," Meade said. "Any money in U.S. dollars is replaced with a debit card in the amount of that money. The debit card doesn't work in Mexico. And border patrol policy is to throw away personal property after 30 days."

President Obama recently issued an executive order that offered a legal reprieve to undocumented parents of U.S. citizens and expanded the program that allowed young immigrants who arrived as children to apply for a deportation deferral. It's unknown what the overall impact Obama's executive order will have on the deportation process.

Meade was critical of the Mexican Immigration Authority, which is responsible for providing assistance to those deported to Mexico from the United States.

"When they're deported they don't have money and they don't have an ID card," Meade said. "The Mexican Immigration Authority are supposed to help these people. Most people don't seem to know that they're eligible for help though.

"Because of deportation, they become homeless."

Why so many deportations?

According to Eric Frost, the director of the Homeland Security Program and a political science professor at San Diego State University, the reason for the record-setting number of deportations can be attributed at least partially to prison overcrowding in the United States.

"Overcrowding in prisons equals one of the ways jurisdictions are saying they can reduce the number of people they can care for," Frost said. "The deportations have taken place because of what the laws are. This protocol is way easier to deport people. People don't want to pay the cost of overcrowding in prisons."

Frost said that the deportation of U.S. prisoners who are in the country illegally is a much easier means of solving the prison overcrowding problem than dealing with the prisoners directly, particularly given the relative ease of the necessary paperwork to deport a prisoner who is an illegal resident.

"Society deems putting a murderer on parole unacceptable whereas deporting them is easy to accept," Frost said. "These are the unintended consequences of dealing with overcrowding in prisons. People don't want to pay for the cost."

Alex Franco, 33, is one such deportee who was transferred directly from a U.S. prison to Tijuana. Franco was born in Mexico but moved with his family to the U.S. when he was an infant. He had spent nearly his entire life in the U.S. before being arrested and deported two years ago.

"I was in a car and we had drugs," Franco said. "Cocaine, crack, and marijuana."

Franco spent two years in prison before the U.S. deported him across the border to Tijuana. His entire family remains in the U.S.; Franco doesn't know if he's going to return because of the difficulty in obtaining an identification card and crossing the border.

El Bordo by the numbers

Local academics and journalists with Tijuana newspapers have conducted research on El Bordo. Among them is Laura Velasco Ortiz, who has written about border issues for Tijuana's prestigious higher education institution El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Colef).

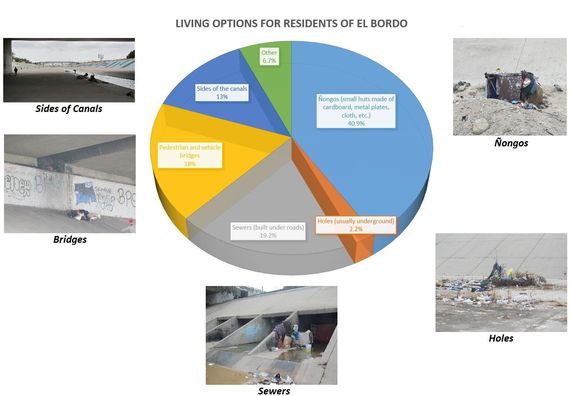

According to Ortiz, the living options of El Bordo's residents include ñongos (small huts made of cardboard, metal plates, cloth, etc.), holes, sewers, pedestrian and vehicle bridges, and sides of canals.

Ortiz said that academics from Colef and journalists at local Tijuana newspapers estimate El Bordo's population to be above 4,000 people. Ortiz found some information using survey methodology about El Bordo's residents. Among them:

- 96 percent are men.

- 67.3 percent have children.

- The average age of an El Bordo resident is 40.8.

- Nearly half of El Bordo's residents speak English.

- The education level of El Bordo's residents is nearly identical to those of Tijuana's overall populace.

- 72.6 percent of people living in El Bordo have no ID of any kind.

A mission aims to help

The plight of El Bordo's residents isn't entirely in despair. Numerous missions and shelters in Tijuana are helping the homeless in El Bordo. One mission, Desayunador, has a soup kitchen, barbershop, makeshift medical center, phone center, showers, a counseling center, and beds.

Desayunador has one American volunteer. Brigitte Beas, who travels regularly from her current hometown of Cardiff-by-the-Sea to assist with the homeless people of El Bordo.

"My goal is to bridge access for the homeless people of El Bordo to American resources," Beas said. "They're 20 minutes away from us and they shouldn't be living in these dire circumstances. I'm hoping to raise awareness about their circumstances, the language barrier, how they live in fear, and don't have any money."

Beas said that after morning mass at Desayunador, approximately 1,500 people line up daily for food.

"They have the soup kitchen at the bottom level," Beas said. "The middle level offers a barbershop to clean them up and make them presentable for meetings with potential employers and government officials."

Beas started volunteering at Desayunador after visiting Tijuana and witnessing the dire conditions in El Bordo.

MULTIMEDIA: During one of her many visits to the border, Beas described the living conditions in the canal and the background of the El Bordo populace.

The current leader of Desayunador is Oscar Torres Hernandez, who came to the mission seven months ago after being transferred through the congregation. Desayunador struggles to maintain operations with limited government and Catholic Church assistance. Hernandez puts great effort in raising funds and gathering resources for the mission's sustainability as it continues to assist the homeless population of El Bordo and others in the area.

Hernandez has noticed a pattern among the residents of El Bordo.

"A lot of people in El Bordo have families who are in America and have American papers," Hernandez said. "They're born in Mexico but their kids are American. They've spent their entire lives in America. Their families come here and help them when they can, which is a reason why there are so many people in El Bordo."

Police difficulty

While it's unclear as to what government agency has jurisdictional authority over the area, Tijuana police regularly raid the Canal, forcing people from their makeshift homes and burning all items they come across.

"It's a jurisdictional nightmare in Tijuana because it was designed as a drainage canal so the federal water agency has jurisdiction," Meade said. "The municipal police in Tijuana don't have any jurisdiction in El Bordo. Tijuana officials are extremely frustrated about this."

Meade cited Tijuana's business community as a primary culprit for the aggressive tactics towards El Bordo's homeless populace.

"Business owners in Tijuana associate the homeless population with every crime imaginable," Meade said.

Despite repeated attempts for a statement and clarification from Mexican authorities as to which organization has jurisdiction of the Tijuana Canal and why they conduct the raids, no officials with the Mexican government would comment for this story.

When told about the lack of response from the Mexican government, Frost wasn't surprised.

"In Mexico there's a threat that if you talk about a potentially controversial issue, you're going to lose your job," Frost said.

What particularly frustrates the residents of El Bordo is the harassment they receive from Tijuana's police force when they leave the canal and enter the city. Police officers routinely question them and seize their property if they leave El Bordo and venture near the city's businesses.

It's unknown if a police presence in El Bordo is legal.

Obtaining identification in Mexico

Most of the residents of El Bordo try to obtain a birth certificate so they can then get an identification card and attempt to return to the U.S. For most of the homeless though, getting the paperwork is nearly impossible.

"They ask you for details like your mom and dad's names," Franco said. "I'm from Mexico City, so it takes two months to get my birth certificate."

Franco said the government charges a fee of $30 to receive a birth certificate.

"How am I going to get $30?" Franco said. "I can't even come out (of El Bordo). When I try to come out, the police are after us."

Desayunador helped Franco get the money for a birth certificate. And the Tijuana police, during a raid in El Bordo, took it away.

SLIDESHOW: Franco explained the process of obtaining identification in Mexico, and how the Tijuana police make living in El Bordo harder than it already is by regularly seizing the possessions of the residents. Including their birth certificates, which are needed to obtain an ID card.

Celso Delgado is a resident of El Bordo who, like Franco, lived in the U.S. for most of his life before being deported to his birth country of Mexico. Unlike Franco, Delgado wasn't deported as a prisoner but rather was working on a farm in California picking fruit when U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) took him into custody as he was leaving the fields.

Delgado has lived in El Bordo for close to two years. Despite repeated attempts to join his family in the U.S., he doesn't see much hope of returning given the cost and repeated confiscations of personal property by the Tijuana police.

"I've never had a birth certificate here, and I don't want to get one because the police don't respect IDs," Delgado said. "They tear them up and throw them away. Even if you have one, they'll take you to jail."

According to Delgado, the police repeatedly tell him and other El Bordo residents that they should leave Tijuana and go back to the southern region of the country where most of them are originally from. The unwelcoming sentiments of the police and Tijuana's business community seem to resonate with most of El Bordo's residents, who are hesitant to leave the canal to get an identification card and attempt to return to the U.S.

Beas doesn't agree with Tijuana police and anyone else who stereotype the homeless in El Bordo as being criminals or having mental illness.

"There's a relative lack of psychological issues with the homeless in El Bordo," Beas said. "They're the victims of unfortunate circumstances."

Everard Meade agrees.

"Deportation is a primary determinant of homelessness," Meade said. "Particularly in El Bordo."

The original version of this story was published courtesy of the Journalism & Media Studies department at San Diego State University.