Like so much else in life, travel changes its shape slowly. There aren't any announcements from the bridge that things will be different, now that you've sailed or flown into a new world. E-tickets take over from the cardboard kind, upstart airlines elbow out the big traditional names, and we get used to the new--trip by trip, hour by hour, day by day.

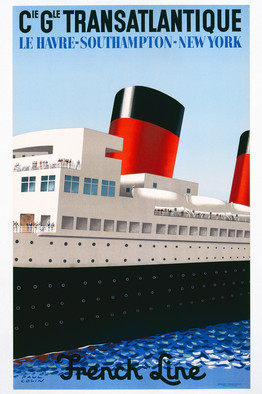

But for me there is one sea change of this sort that, although I've had time to absorb it, still refuses to seem real. It is the simple fact that the Atlantic Ocean between New York and Southampton, Boston and Dublin, Montréal and Le Havre, is no longer full of passengers on ships.

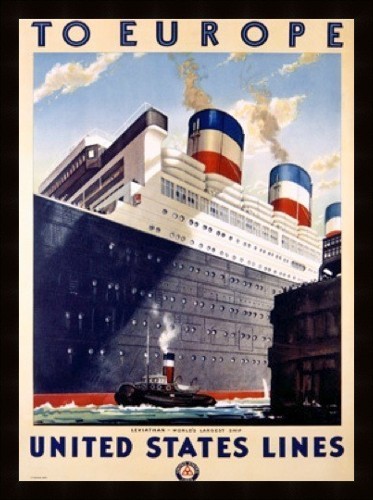

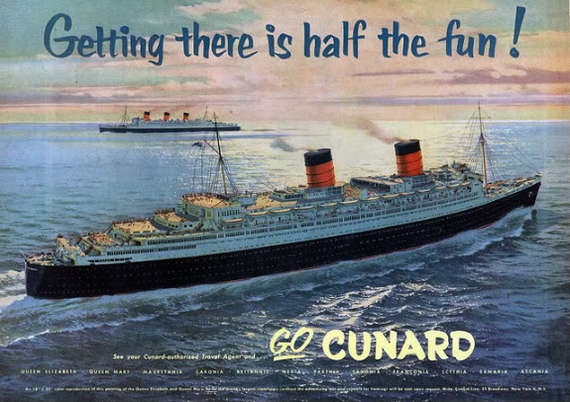

I grew up in Chelsea, on Manhattan's West Side, watching from our rooftop as ocean liners like the Queen Mary, the France, and the United States steamed up the choppy Hudson. I would bring up binoculars to keep track as they obeyed their tugboats and disappeared into their piers. Then I'd run up the stairs again to see them sail back out, and wish I could invent a way to get aboard.

Later, I did sail out on the first Queen Elizabeth, when my parents moved us to London--an adventure that, years later, inspired one of my children's books, My Ocean Liner. My brother and I tried to explore every deck of this steel world, and began to believe that it was a building like the one we lived in, one that was tipped on its side. But this horizontal version of our home could not be torn down. With all its wave-cutting power, its rivets of iron, its interior ways of life, it was a thing that could not die.

But it did die, finally coming to rest at the bottom of Hong Kong Harbor. And most of its peers are dead, too, including the last two liners built specifically for the North Atlantic, Cunard's Queen Elizabeth II and Norwegian Cruise Line's Norway (once the France).

To this day it seems like a strange dream to me that the fleets of Atlantic liners--the day-to-day, for-travel-not-for-idling liners--are gone. Wooden deck chairs, tartan blankets, beef bouillon in bad weather, rope coils called "quoits": Little traditions filled up your five or six days out of sight of land. That, and making it through a high and deep domain that seemed as dangerous as the moon.

Today's nautical world is one of cruise ships designed for warm-water forays--floating hotels that sail passengers back to where they began. Those who hope to make a true ocean crossing aboard ship are running out of time. At least two options are still out there: seasonal repositioning cruises that take place when a ship is being transferred from the Caribbean to the Mediterranean, or the other way around. And there are Cunard ships such as the Queen Mary II, which, at least for now, are still tackling the New York-to-England trip.

To try and get a taste of traditional ocean liner life before it was too late, my wife and I made two voyages some time back. One was to a German grand hotel, The Hotel Atlantic in Hamburg, which had been built in 1909 for passengers with bookings on ships, and is still going strong. The other was an Atlantic crossing in a tiny, porthole-less cabin on the QE2: All we could afford.

Owned by a chain of luxury lodgings called Kempinski, The Hotel Atlantic has a foam-white gabled facade and, like a liner in port, looks out over water (a lake known as the Alster). What I loved best were the hotel's nautical touches, added to get guests accustomed to the vessels they were about to board. Carpets are adorned with globes and coils of ropes. Doors open out into hallways, not into rooms. And, in seafaring high style, the stairways get wider and grander the closer you get to lobbies and main landings.

As for our QE2 ocean crossing, I was happy that it was full of storms. For me, a Caribbean cruise lacks the element of adventure. Sign on for an April Atlantic trip, like ours, and you end up in watery valleys that, unlike those in a landscape, are constantly reshaped by wind and weather. The light in the Atlantic is more fickle than any other. One minute, silver sparkles from every wave; the next, the ocean has stolen the color of the seagulls that fly over it: blue-gray, with tips of white.

The QE2, like other ships, had one of its TV channels tuned to a round-the-clock view from the bridge. The ship's bookstore manager told me that she had been lying in her cabin one stormy night and snapped this on. Instead of the usual view of the ship's prow, with the moonlit sea scrolling past, she saw a mountain of white rising in front of the camera. A second later she was tossed out of bed, when a giant rogue wave hit the QE2 head-on. The ship sailed on without damage, but the passengers and crew couldn't forget the sensation of running into this wall of water.

Our crossing started off with two rough, prototypically Atlantic days. This leg of the journey contained the captain's reception for passengers in the elite Queen's Grill and Princess's Grill dining rooms. My wife and I sat with our drinks in the Chart Room Bar and watched a parade of men in tuxedos and women in sequined gowns staggering as each new swell thundered into the sturdy hull of the ship.

This was weather from the bad old days of sailing--weather that the rivets and the liners themselves knew they had to push through. But no one I saw missed a step or let go of a full glass.

For a second, ours was a ship of intrepid travelers, of those who kept on going where they needed to go. Some made heroic thrusts of outstretched hands to stay in balance. Some held on to chairs or stools at the bar.

A few, like me, looked out the window into an apocalypse of foam, and smiled.

* * *

Mandel's My Ocean Liner: Across the North Atlantic on the Great Ship Normandie includes an introduction by the late John Maxtone-Graham, an authority on the world's great ships. Maxtone-Graham passed away earlier this summer.

Peter Mandel is also the author of the read-aloud bestseller Jackhammer Sam (Macmillan/Roaring Brook) and other books for kids, including Zoo Ah-Choooo (Holiday House) and Bun, Onion, Burger (Simon & Schuster).