In 1980, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held a retrospective of the work of Pablo Picasso organized in cooperation with the French Government. Picasso had died in 1973; a few years earlier, most assuredly in anticipation of his death, they had passed a law saying that works of art could be donated to the state in lieu of estate taxes (un 'dation') provided they were culturally significant. The French are no dopes when it comes to culture: they swooped in and chose the very best things for what was to eventually become a new Picasso museum in the Marais district, leaving the heirs with substantial, yet diminished holdings.

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907, Oil on canvas, 8' x 7' 8" (243.9 x 233.7 cm) Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest, c. 2007 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907, Oil on canvas, 8' x 7' 8" (243.9 x 233.7 cm) Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest, c. 2007 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

While MoMA was piggybacking its exhibition to the 'dation', WNET, the public television station in NY known for its arts programming, quickly got in line behind the Modern to produce a television special on Picasso in conjuction with the exhibition. It made perfect sense: as MoMA was linked with all the important players, entree for the film production team would theoretically be seamless providing an instant boost in both credibility and access.

In truth, it was a hornet's nest of children, grandchildren, wives, and mistresses, all eager to hold close to what they felt was rightfully theirs.

What was needed for the film really had very little to do with what could be captured via the museum. Of course the curatorial advice would be invaluable in pointing the way towards certain people and collections and lead to sources for the many transparencies of the works of art; but the vast amount of material--photographs, archival film footage, interviews--was not something that had preoccupied their curators and staff.

Though Perry Miller Adato, the filmmaker, had hired an associate producer and someone to chase the transparencies, she realized early on that she was entering the highly specialized realm of the greatest, most prodigious artist of the twentieth century and that it was not going to be the same as making a film on Georgia O'Keefe, her previous project (though each film of course has its own exigencies). She was going to need troop strength.

There was one foot soldier at WNET who had worked for both the French Government and for MoMA and whose job it was to pass the hat for arts programming and thus was inadvertently positioned to know the players from all three teams plus know how to get it funded.

I thought the gods of fortune had finally smiled down on me. The subject himself, however (who also thought of himself as God) had other ideas, regularly sending gremlins from beyond the grave to make progress herky jerky at best.

Though the production credit eventually read "Production Associate", in fact what I became was the wrangler, convincer, persuader, flirt, peacemaker, and money honey; this babe into the cold bath method is good for reminiscing purposes only and has little value as you try to dodge the bullets of assorted cranky friends and family who are missing their fix of Pablo and are taking it out on you, the person least likely to be able to do anything about it. To have Picasso as your very first assignment--shooting in three countries (also Spain), three languages, under the auspices of three governments--seeking the cooperation of some of the wealthiest and most elusive collectors and institutions and not an insignificant number of loose canons was really an insane way to get into the film biz. (It's possible that getting into the film business in a good way is always oxymoronic)

But more than anything I came up against Picasso: his giant persona which only six years after his death was still present in the lives of everyone he'd ever known and his genius, not only for creating art but creating utter chaos, a specialist in the art of setting any one who loved him against another. I became one of the legions of young women who had been in thrall to him, a mistress to his many moods, only I didn't get any of the upside: the melting looks from the intense brown eyes or the reportedly spectacular sexual prowess.

All the more reason then to be worshipful and impressed at the astounding work of John Richardson who has produced the third volume of his biography of Picasso, The Triumphant Years, published this week to great acclaim. Richardson's unflagging erudition, meticulous reporting, insatiable digging, clever connections, and vast and deep personal knowledge of the players makes this series much closer to a performance piece of biography , the definitive text.

And because Richardson makes it perfectly clear with engaging narrative and precise scholarship how worthy his subject is, even those who have read about Picasso before will be newly swept away by the intricacies of this complex character. This is not, however, just a tome for insiders, though it helps to have a healthy interest in art and artists.

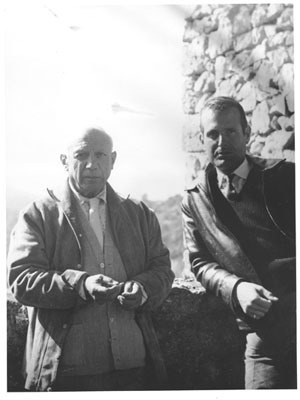

Picasso and author John Richardson at Chateau de Vauvenargues, 1959 Author's collection.

Picasso and author John Richardson at Chateau de Vauvenargues, 1959 Author's collection.

Richardson met Picasso while living with Douglas Cooper (who had himself wanted to write the biography) in the south of France and saw him regularly from the early fifties through the early sixties. He began by thinking he would write about the wives and mistresses of Picasso, the way the artist used art and sex, painting and making love, as metaphors for each other and how the style of his work changed as he changed women--volatile relationships that Dora Maar, herself one of the mistresses, characterized to him as 'first, the plinth, then the doormat". This was the template we used on the film, and it's reductive and catchy, certainly one way to process the gargantuan archive when you only have ninety minutes.

But as Richardson himself says, "Picasso's work is far too protean and paradoxical to be limited to a single reading." And so he abandoned that seductive narrowcasting at the outset in favor of a much more comprehensive and penetrating approach.

One that would more or less take the rest of his life.

Richardson isn't the first to devote most of his life to Pablo, as the volumes make clear. The Picasso bibliography includes everything from kiss and tells to scholarly treatises about the work and any number of memoirs and biographies. (Richardson is impatient and dismissive of some of these earlier efforts, calling them everything from "unreliable" to "rigamarole" or "fairy tale" to outright "wretched" or "sheer fantasy".) But his end result is entirely different. Encyclopedic without being boring, any future artist's biography, or really any biography, will inevitably have to step over Richardson's very high bar.

Occasionally, biographers manage to be fans of their subjects for the duration. It's hard to love someone unreservedly whom you come to know so intimately-- Richardson doesn't shy away from scandal, rather he is propelled by it, and sometimes, if this works to Picasso's disadvantage, so be it. Looking at a life from the perspective of the warts and all can produce battle fatigue but at the end of the third volume (the ballets, the project for a memorial to Apollinaire, the bourgeoise life with Olga, the flirtation with Sara and Gerald Murphy, the rebellious hedonism of his attraction to the seventeen year old Marie Therese) with Picasso shrugging off Surrealism and heading for the shattering Guernica, one still feels Richardson's magnificent enthusiasms for the moods, the settings, the entourages that may have influenced him; the motivations, the myth-busting, the sexual/historical/empirical digressions often taking us far afield only to bring us back a bit later with a much richer understanding of what made this man, and his world, tick.

The volumes look and are dense, (Volume 1 ranges from 1881-1906, Volume 2 from 1907- 1916 and Volume 3 from 1917-1932) but they are intensely readable--chatty, personal, with mini- biographies of others in the Picasso circle--so that we come to know just how convoluted and complex the roots of the art were with Pablo often devouring the hands that were feeding him. The tangents, however "vaut le detour" and are every bit as juicy as the three star view of the man himself. Often, Richardson makes patently clear, Picasso was conceptually leagues ahead of everyone else. But at times he was in debt to other geniuses who were his friends and competitors-Braque, Gaugin, Matisse, Seurat--and to the other protean talents from whom he freely stole(Manet, Ingres) ideas and images.

Picasso. Mother and Child, 1922. Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collectaion formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, MD. BMA.1950.279

Picasso. Mother and Child, 1922. Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collectaion formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, MD. BMA.1950.279

The normally heavy lifting of biography thus seems like gossamer in his hands, the facts arranged in such a way as to ease you on down the road with the tone of a confidence or a wink. The iconography of each important work is disarmingly traced, threading the personal and professional antecedents into one comprehensive whole. There are no sacred cows for Richardson--and like a cat he sneaks up and circles the truth and then pounces on it, explaining the artistic breakthroughs, the changes from one style to another, the sexuality and drugs which fueled some of them, and Picasso's own drama-king ego that self-mythologized to the point that he came to believe in the stories too. As a myth debunker Richardson, however, is unsurpassed, adroit at peeling the layers: first, those of Picasso himself, then the second generation contemporary witnesses who often rewrote history, then the third generation anecdotal whispers, the fourth generation scholarly reckoning, and so on, often a daisy chain of prior confabulation.

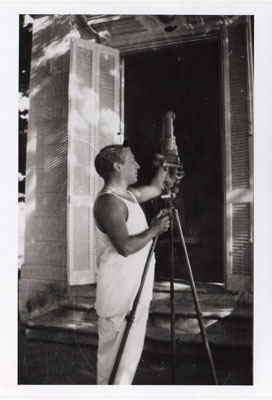

Picasso, Juan-les-Pins, 1926. Collection Kimberley Greeley Brown, Courtesy Kenneth WaynePhotographer unknown, all rights reserved.

Picasso, Juan-les-Pins, 1926. Collection Kimberley Greeley Brown, Courtesy Kenneth WaynePhotographer unknown, all rights reserved.

Richardson leaves no dwelling, no voyage, no influence (the wonders he saw and appropriated into his own work), no woman, no friend , or enemy uncharted. One resists the tendency to makes lists only with difficulty: the houses (in Volume Three alone: Montrouge, rue la Boetie, le Gueridon, La Vigie, la belle Rose, la Haie Blance, Boisgeloup), the Women (madcap Fernande, lissome Eva, bourgeoise Olga, , sexpot Marie Therese, free spirited Francoise, imposing Jacqueline), the friends (Apollinaire, Cocteau, Jacob, Breton, Gertrude Stein, Stravinsky, Diaghilev) and the enemies and some that straddled the two camps, the Dealers (Kahnweiler, Rosenberg), the ballets (Parade, Tricorne, Pulcinella, Mercure, L'epoque des Duchesses, La Danse), the Museums, (besides Paris, Antibes, Barcelona and now Malaga) the Galleries, the retrospectives and exhibitions, the media (paint, sculpture, photography, poetry, collage, tapestry). All come under his watchful, painstaking and often bemused eye.

Richardson's gift for language also has the added bonus of a mini-tutorial in French and Spanish slang --gratin (high society), bien couillarde (ballsy, or well hung), tertulia (group of friends).

And as far as wrangling goes, Richardson is unrivaled. Some of the images were a revelation to me; many classified or in private collections that were being carefully concealed at the time of the documentary. (Richardson has had the help of Marilyn McCully who was also consultant to WNET on the Spanish period) but his long personal cultivation of so many of the Picasso personages has reaped its rewards and the astonishing selection of photographs from the Olga years in Volume Three is testament to this.

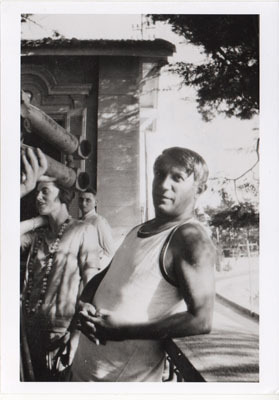

Picasso, Olga and Jean Hugo, Juan-les-Pins, 1926. Collection Kimberley Greeley Brown, Courtesy Kenneth Wayne Photographer unknown, all rights reserved.

Picasso, Olga and Jean Hugo, Juan-les-Pins, 1926. Collection Kimberley Greeley Brown, Courtesy Kenneth Wayne Photographer unknown, all rights reserved.

Richardson notes that for most of his life, Picasso was already in the spotlight, that the tributes and retrospectives one normally gets at the end had been ongoing since his twenties. Little details, why Picasso's black was blacker than black (he added silver powder) or his relationship with Chanel (one night stands) make the reading lively. But it also helps to be reminded of his early genius, the sheer power of his intellectual and instinctive audacity--the breakthrough Demoiselles D'Avignon for example,was painted when he was 25!

In short, Richardson seems to have found a way to see Picasso plain while at the same time respecting his obviously century-dominating genius. Fernande, an early "official" mistress apparently said, "He who neglects me, loses me" and Picasso might well have intimated the same thing. Fear not, Richardson has made amply sure we won't.

My own notes are filled with the often conflicting imperatives of the various art historical players--"stay away from War and Peace" (about a work perceived to be of lesser quality), " Paloma and Claude's role should be kept subsidiary" (except that they were controlling his reproduction rights) and "Don't say to Jacqueline" (about the obvious influence of another woman)-- and who I should take to dinner and speak to off the record.

In the end, after an endless number of three-course meals for all the consultants and experts, (and shooting in France where lunch for the crew is not just a table prepped by craft services), I still had only modest success. Jacqueline, Picasso's wife who survived him, received us but would not be filmed. (At her death, another 'dation' of Picasso works went to the state.) Julie Man Ray, who was still living in the home/studio she had shared with Man Ray was her showgirl self--greeting me in full makeup and with a theatricality I'll never forget, yet was vague about the whereabouts of some of the photographs. Claude and Paloma, both closer to my age, were easy and friendly, having been thrust into the role of gatekeepers well before their time.

My quest to see Dora Maar though, preoccupied me. Already my favorite of the women for her dark and independent ways and the often tragic way Picasso had portrayed her, she played cat and mouse, writing me welcoming letters and then becoming suddenly unavailable as the date drew near for me to see her. (One letter I have from her actually asks for John Richardson's whereabouts though, which only proves his gift for connection.) In last night's tepid sale at Sotheby's, one of the most successful lots was a bronze bust of Dora that went for 26 million dollars!

Of course I was merely a cog in the endless wheel of Picasso, one in which friends, friends of friends, lovers spurned and desired, and scholars of every stripe have been just so many waystations, however influential at the time, on Picasso's road to immortality.

Interlaced with the tortured pages of my seven production notebooks for the Picasso film are scribbled notes in the margins for my wedding, another production which was also pending. In harmony with all the work I was doing in France are lists of Malmaison-patterned silverware settings I was hoping to receive as loot, and rather pretentious ideas about the wedding menu --of soupe de truffe and mousse de homard and lots of overpriced Dom Ruinart champagne.

We could all probably use a little more of what Picasso had. But perhaps I do have a tiny distinction in the legions of his acolytes after all: I'm probably among the few women who ever spent all day thinking about Picasso but dared dream of another man at night.

Picasso. The Lovers, 1923, Chester Dale Collection, Image c. 2007 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1963.10.195

Picasso. The Lovers, 1923, Chester Dale Collection, Image c. 2007 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1963.10.195