It's hard not to gush about William Kentridge.

Part shaman, part tech wizard, part entrepreneur, part educator, part apostle, part witness, part historian. Or you could just say that his definition of an artist encompasses all these things.

Double Shadows. Video courtesy William Kentridge.

Sometimes he is like Harold with his Purple Crayon, (though he likens himself to "Persephone with a ball of string"), a Pied Piper of a simple charcoal line that we follow, no matter where it goes. At other times, he is a Stan Laurel, chatting with multiple images of himself as they (he) toss in bed at 4 a.m. over a project, or fidget in a chair. Sometimes he is a horse, practicing hunched over in multiples across the screen, trying to get the arc and the gait just right. And at other moments he is Merlin, pulling birds and sheets of paper out of thin air.

Making a Horse. Video courtesy William Kentridge.

William Kentridge, whose exhibition William Kentridge: Five Themes at the Museum of Modern Art charts the titular five themes that have preoccupied him, is trying to make "sense of things, which is half of who we are."

One of his selves materializes to chat with me for a quiet moment amidst the hoopla of the opening for the exhibition at its first stop in San Francisco. Once you have seen the comprehensive survey and the marvelous accompanying catalog and DVD (the two videos loaded especially for HuffPost represent a behind-the-scenes intimate looks at his process), it is impossible to believe one man could generate so much high-caliber and provocative work.

I ask him how he decides which project from amongst the many he has going simultaneously he will work on each day, and he says right now he is focusing all his energies on The Nose, a new opera project for the Metropolitan Opera. (He has already done two operas: Mozart's The Magic Flute and Monteverdi's The Return of Ulysses). He also tells me with a little bit of legerdemain that he is also working on some "large flowers, some large scale flowers, peonies" and a "new film" which will revisit his earlier work about Felix and Soho (an earlier example in the survey), yet two more alter egos who once represented the artist and the businessman sides of him.

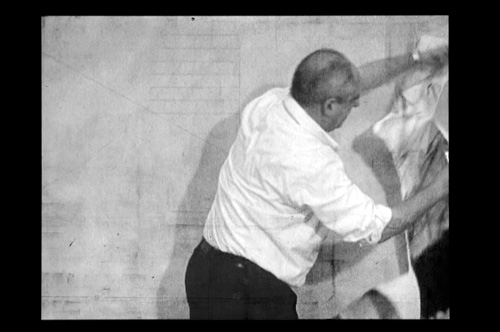

He seems calm, secure, always somewhat formally dressed in a white undershirt and white button down shirt and a pair of black pants, the "uniform" that transcends the selves since he claims to have "no sense of fashion," but which I find extremely fashionable for an artist who does things like pratfalling on floors and twirling like a dervish. Kentridge says he is inspired by Manet, and there is something of the master's chiaroscuro even in the way he dresses.

But the day after our quiet talk when he presents his film/performance project, I am not me the horse is not mine, the warm-up to the The Nose, I understand better about his multiple selves, a "man who is divided against himself".

What must it be like to live in his orbit? He admits his wife was apparently miffed after she appeared in one of his films nude and their children scolded her, "If you don't want to be in William's (domestic) pornography, don't take your clothes off!" Yet there she is again, in "I am not me...", the blanket-covered solid sleeper he tosses against as he frets over work at 4 a.m., (an artist is "at work even when he sleeps... re-organizing" things in his head.) The middle of the night panic is fertile territory for his multiple selves to gang up on each other, each of them defending his turf, finishing each other's sentences. "To what extent," he asks a bit later, is the artist "in control of his own person?"

William Kentridge, Invisible Mending (still), from 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, 2003; 35mm and 16mm animated film transferred to video, 1:20 min.; Collection of the artist, courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg; © 2008 William Kentridge; photo: John Hodgkiss, courtesy the artist

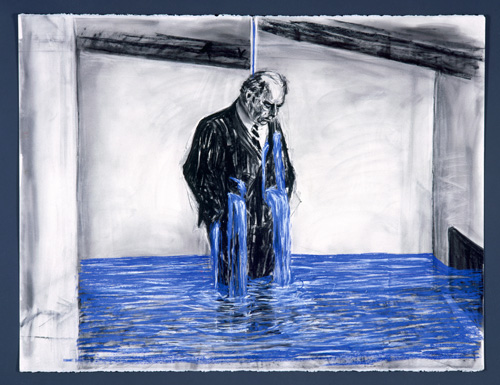

William Kentridge, Drawing for the film Stereoscope [Felix Crying], 1998-99; Charcoal, pastel, and colored pencil on paper; 47 1/4 x 63 in. (120 x 160 cm); The Museum of Modern Art, New York; © 2008 William Kentridge; photo: courtesy the artist and The Museum of Modern Art, New York

His work sounds very Dada, and Gertrude Stein, very surreal and of the moment too, and some of it harkens back to Duchamp and Man Ray and Dali and Bunuel, even down to the ants scurrying around in the iris of a film and objects falling from the ceiling. But that is part of the genius: I believe Kentridge entirely when he shows us this restless insomniac. You couldn't possibly have his prodigious output in so many disciplines and not lose sleep over it.

Even though he is a visual artist, words are very important to him, often the genesis of the project. First come the words, then the lists, then the themes, then the project. "As if words could make ideas." Then, what comes next? "Are we following the line or is the line leading us around like a dog on a leash?" he asks the audience during his performance.

He sounds like the actor he once was in Johannesburg, yet instead of theater, he dreams film or opera. "There is more going on for me", he says and laughs when I suggest perhaps he has a version of artistic ADD; he does not to want to be able to decide ahead of time where he is going with something. His work is wholly original, playful, yet deadly serious.

William Kentridge, Bridge, 2001; Bronze and books, 32 5/8 x 36 3/4 x 7 1/2 in. (60 x 93.2 x 19 cm); Collection of the artist, courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg; © 2008 William Kentridge; photo: John Hodgkiss, courtesy the artist

William Kentridge, Drawing for the opera The Magic Flute, 2004-5; Charcoal, pastel, colored pencil, and collage on paper; 31 1/2 x 47 1/4 in. (80 x 120 cm); Private collection, Ross, California; © 2008 William Kentridge; photo: John Hodgkiss, courtesy the artist

How much of the outside world do we need inside us," he asks?

He has a few assistants, but he does all his own drawing and film making, a handmade animation filled with torn paper and sly stage business and twinkling lights and birds and painstaking movement and now and then some stock footage that adds up to something unique with unforeseen consequences.

His art has commented extensively on apartheid and the tyranny of group think. I ask him about Obama. He is moderate in his response since, after all, he is "just another American president" but obviously an improvement on previous administrations. He suggests we don't want politicians to lead artists anyway, because after all look what happened when world leaders were interested in art --"Stalin and Hitler." Kentridge's work is firmly situated in the political realm, even though he says at one point, " I am only the artist; my job is just to make the drawings" -- truth, the truth about memory, reconciling personal, as well as public events, these are the things that keep him up at night.

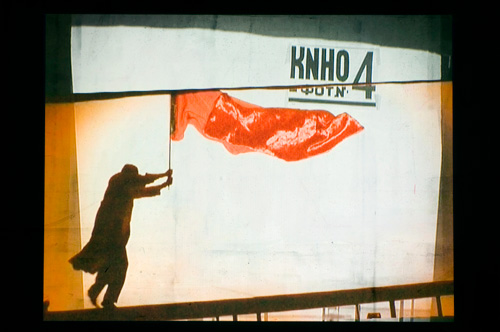

William Kentridge, A Lifetime of Enthusiasm (still), from the installation I am not me, the horse is not mine, 2008; Eight-channel video projection, DVCAM and HDV transferred to video, 6:01 min.; Collection of the artist; © 2008 William Kentridge; photo: John Hodgkiss, courtesy the artist

William Kentridge, His Majesty, the Nose (still), from the installation I am not me, the horse is not mine, 2008; Eight-channel video projection, DVCAM and HDV transferred to video, 6:01 min.; Collection of the artist; © 2008 William Kentridge; photo: John Hodgkiss, courtesy the artist

Shostakovich's opera, which is his source for the new opera, is about "a nose on the loose." It was inspired by a short story of Gogol's about a bureaucrat who loses his nose and, even when he finds it, cannot manage to stick back on his face. Kentridge traces its bumpy, century-long gestation in I am not me... to Tristam Shandy and Don Quixote. He has his audience laughing in the palm of his talented hand as shares the struggle that goes on within him, "the bouncing back off the inside of our heads" to make the piece have meaning.

But "understanding where our understanding ends" is half the battle. "It's as though a simultaneous translator has gone to an island where there is no cell phone contact."

At the end of our chat, I tell him laughingly that I am going to be his groupie this year -- and I ask him how to entice readers who care a great deal about politics but maybe not as much about art. And he says of course you can't. "Just tell them to come," he says.

So I am telling you. Come. You will be excited, charmed and wildly stimulated.

The exhibition opens February 24th at MoMA, runs February 28-May 17, and then travels to Paris, Vienna, Jerusalem and Amsterdam. Performances of I am Not Me, the Horse is not mine are, alas, sold out, but the opera The Nose will premiere at the Metropolitan Opera on March 5, 2010. The star is Paulo Szot, the Brazilian baritone who is best known for his Tony-Award-winning appearance in Lincoln Center Theater's revival of South Pacific.

This post updated from an earlier version on 3/20/09.