As an insomniac, I was always intrigued by the story of the genesis of the Bach masterwork, the Goldberg Variations (versions by Glenn Gould, Murray Perahia, and Simone Dinnerstein): Bach wrote the theme and thirty variations, mostly in the key of G major, for his pupil Johann Goldberg, "in order to sweeten the nights of the insomniac Count Keyserlingk, Goldberg's employer", according to Deborah Jowitt, one of three biographers of Jerome Robbins. Robbins was looking for a challenge, something "very big and architectural" after his previous Chopin ballets.

As a way of counting sheep, ballet had been the opposite for me: as a young dancer with Balanchine's School of American Ballet, I had to be driven into NYC almost daily for after-school lessons. My mother could never find a parking spot (this was when the school was on upper Broadway, before Lincoln Center) so she would routinely be late to fetch me, and I would wait nervously at the top of the proverbial steep and narrow staircase for her on cold, dark winter nights. I was sure she was going to abandon me as she was not happy about having to make the onerous commute (these were the days before we slavishly gave our lives over to the children) and so I became tightly wound, often unable to sleep after we got home, holding thumb to forefinger in a circle, practicing the technical, rigid way they made us position our hands in bed well into the night.

The three biographies tell the story the creation of the Goldberg Variations more or less the same way: Robbins was depressed and alone during the year of its inception to the first performance. Though this was well before the phrase "the one" was in vogue, in fact, he despaired of finding someone to share his life with--a gay man who loved women too. Some say the ballet reflected this lonely time--"an intellectual effort which deconstructed the brilliant music from which it sprang". It wasn't (and isn't) universally well received.

But I felt, and still feel, completely differently. It introduced me to the gorgeous music, and not incidentally, to everything the dance stood for. My two best girlfriends had spent that summer working as ushers at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center; Goldberg went up as a work in progress there, accompanied first by harpsichord (now it's only piano). I was getting ready to go to school in Paris so my friends were there without me, even though it was I who had been the ballerina. But they brought home vivid, enthusiastic memories of it and also friendships with some of the male dancers in the cast, so I felt close to the ballet, though in a different way.

Image courtesy of Martha Swope

Goldberg isn't just like dance, or even like architecture, though its gestures and steps pay careful homage to the complicated sarabandes, gigues, toccatas and canons and make you understand musical construction better than any course you could take at school. Robbins said about the music that it was, "a tremendous arc through a whole cycle of life and then...back to the beginning." The Goldberg couples are open and vulnerable to each other: they are female and male, in pairs and trios and other combinations. They play games, they flirt, they gambol, they carefully observe each other, echoing steps, embellishing them and passing them back with just a little extra spice, just like you would your favorite recipe for boeuf bourguinon. Sometimes we carefully pick our way through the minefields of love and friendship, other times we run roughshod over or roll under each other. All of this is carefully laid out in the Goldberg Variations. Amanda Vaill, another biographer, succinctly describes the costuming for the piece, which is as much an element as the steps "...the opening theme is danced by a couple in modified eighteenth century dress while the dancers in the first half wear practice clothes and then, in the second half add bits of pieces of costume until the final variation when all come onstage in eighteenth century regalia to pose as if for a group portrait--whereupon the stage clears and the first couple returns to restate the theme, this time striped to practice clothes".

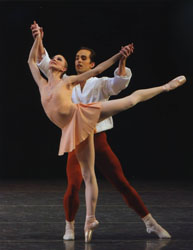

New York City Ballet, courtesy of Paul Kolnik

Think of it: you come into a party, you meet a man, or a woman. You're all decked out--you look wonderful as you present yourself to the world, but your fancy clothes are your armor. You take his measure, and he yours. You imagine him without his clothes. Gradually, you get to know each other and everything is indeed stripped away; you are naked, exposed. You are comfortable undressed. Slowly, you begin to add layers, only to topple over in each successive wave of getting-to-know-you; you learn each others' histories, and about the rest of the orbit--friends, family, work--each one adding a little vestment of protection. All of a sudden, you find yourself dressed again! And you have to start all over.

The ballet hasn't been in repertory for a couple of years, and I hadn't seen it in decades. Last week, I watched Christine Redpath, former NYCB dancer, one of the ballet mistresses for the Robbins Trust, rehearse the ballet with her Golden Retriever Emma at her feet. Still lithe, filled with energy, she demonstrated and gave great notes that occasionally had to do with tech stuff but just as often dealt with the emotion or logic of a movement; like an Stanislavski teacher giving actors their motivation: e.g.when you lay on beach and are startled don't react as if it's a gunshot,; when you walk, walk towards something. The women looked young and diminutive; some of the men are slight too, though many tall and athletic, all smiling, joking with unfeigned affection, tickling each other under the arms as they execute a step. Some have bleeding feet (no one wears tights) which are being stuffed into toe shoes with rubber packs or tape. Routine pain for enormous gain. Adam Hendrickson, dervish and birdlike, spins and lifts Megan Fairchild, a tiny, compelling dynamo. Another raises her hand with some frustration, "I need some counts". They perform for each other too, whistling and applauding as a step is nailed with particular flourish. The whole atmosphere is imbued with an openness that Robbins famously did not encourage (he was known as a terror), but is ironically the essence of his ballets.

But by performance time on Saturday night, I'm just holding my breath, hoping it is as winning as the rehearsal was. Though not as perfect technically, (nerves evident), the ballet shows its true colors as not only the most ambitious ballet but one that also wears it heart on its tutu. It is abundant with joy, life affirming, every bit as much of an achievement as the greatest classical ballets. What you are able to see more of in the grander space of the theater is the speed and intricacy of the steps as the dancers chase each other across the stage..... but don't you, too, run after the people you love? Yet the killer adagios, the slow, sensuous pairs of Rachel Rutherford and Jared Angle and Maria Kowroski and Philip Neal and the moxie of Wendy Whelan and Benjamin Millepied in the second half variations, hit you viscerally: bodies in synch with each other, fearlessly trying to make it work.

Rachel Rutherford and Jared Angle, courtesy of Paul Kolnik

As they walk backwards, in circles around the stage, carefully not bumping into each other, I think about people watching each other's backs, protecting them in the down times, lifting them when they need to go up, seeking out love, companionship, being rebuffed, trying again, attacking the same demons over and over, all the while embracing the joys and camaraderie of friendship. It's a joyous coming together of differences, as a friend who attended with me said, like the Dance of Life by Matisse at MoMA. It says everything about relationships: flirtation, consummation, and asks the bigger question, Will you catch me if I fall? It capsulizes the essence of history and how it is present in our lives, and how we should not be afraid since it's the mashup of the backwards and forwards that equals the future. Sometimes we don't know which direction we are going in: we depend on friends and lovers to provide orientation. We also depend on them to challenge us: to throw us high, to somersault under them, to simply let us idle on the beach next to them and trail a finger in the sand.

Sadly, I did not feel this connection from the Saturday night audience (is there bridge and tunnel for ballet too?). Goldberg is a demanding ballet to dance and to watch and to play. It takes eighty minutes and I felt pockets of the audience become subdued not only out of respect but out of impatience. If you don't know the music there are a lot of false positive endings.

We have been talking about outsized ambition these last weeks in the Culture Zohn: Simon Rodia and his Watts Towers, Hillary Clinton and the Presidency, Leni Reifenstahl and her film on the Olympics of 1939, now Bach and Jerry Robbins and the Goldberg Variations. The irony that many geniuses, including Robbins, are tormented when they create their greatest works has never been lost on any of us.

But on the eve of Super Tuesday, it's worth reminding ourselves that daring to dream the impossible dream is a very good thing. Oddly enough, it was in Paris, having finally found my bliss, and relaxed into another way of life, that I began to take ballet class again and not lose sleep over it.

In the penultimate Goldberg variation, the dancers come together as a group in period costume: Look, over there, just in the distance, it's the future and we embrace it, they seem to say; being afraid of not getting the steps right or not pleasing a special patron is not worth staying awake all night for; to stave off connecting is to stave off life.

(The last two performances of the Goldberg Variations are Feb 9 @ 2 and Feb 12th @ 7:30 during the winter season. During the spring season an all Robbins festival will be performed and the Goldberg Variations June 22, 25, 29. Try not to miss it.)