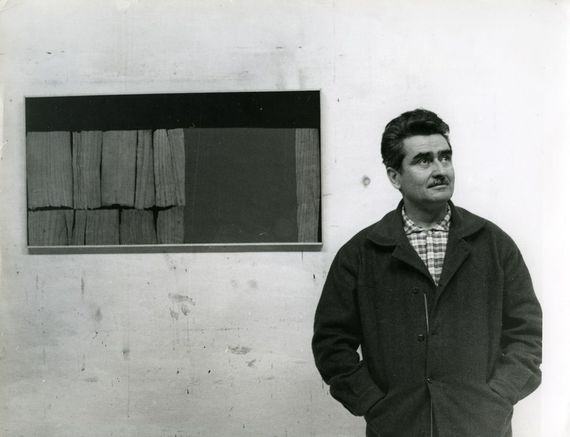

Alberto Burri, courtesy Burri Foundation

Alberto Burri, whose magnificent retrospective is in its last weeks at the Guggenheim was a man who made limonata out of limoni.

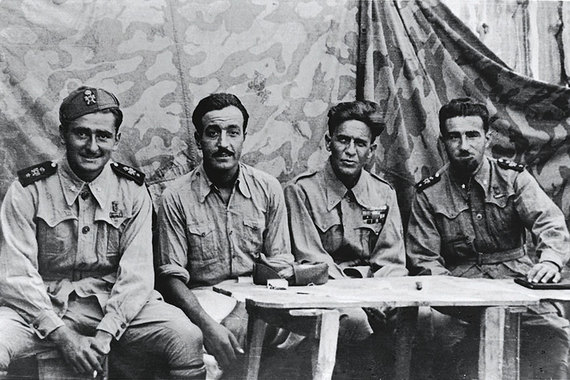

Burri was born in 1915, and became a young fascist when Mussolini represented hope for the ailing Italian post WWI nation. He enlisted and served in campaigns in North Africa and Yugoslavia, eventually serving in the medical corps as a surgeon. Captured in Tunisia, he was sent to a POW camp in Texas.

Burri, at left, during the war, 1935 , courtesy Burri Foundation

Though the Italians were treated better than the Japanese interned in the U.S., he experienced deprivation and depression. During that time, he (and some fellow inmates) began painting as a way of trying to guard his humanity and of processing his disillusionment with politics and the devastation of war. He was entirely self-taught.

He returned to Italy in 1946 to witness the bombed out ruins of his beloved homeland, and then slowly, the laborious post-war Italian reconstruction. As a proud son of Citta di Castello on the Umbrian border, the gradual restoration of something of a normal life meant a great deal. The films of the postwar Italian neorealists offer the most visceral parallels to Burris work. Visconti, Antonioni and Rossellini (as seen in the vivid document here) also drew attention to the harsh postwar conditions.

Like Picasso, whose work is often loosely subdivided according to the stylistic changes that occurred when a new woman came into his life, Burri's work changed according to the materials that he repurposed for his painting: first war cast-offs, then rebuilding materials, then modern plastics and sheet metals. This makes the Burri exhibition exceedingly easy to follow; we progress along with Burri, marveling at the potential he first saw in those unusual materials, the ingenious meta-surgical transformations he wrought, how each built upon the others.

Rosso gobbo, 1950, Courtesy Galleria Tega, Milan (Gobbi series)

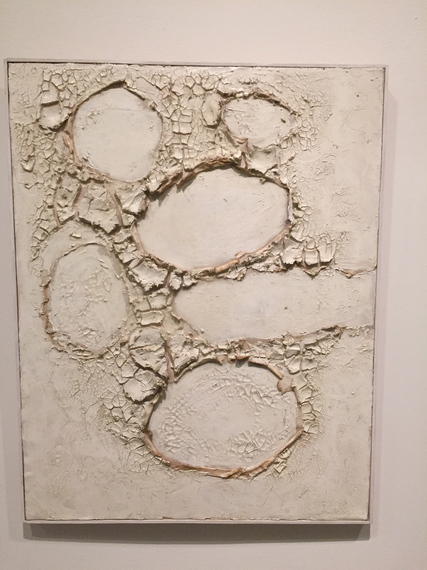

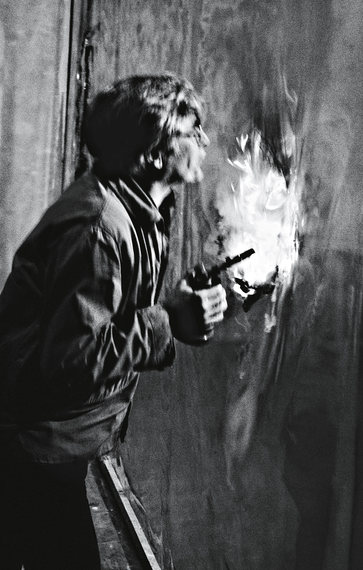

Burri's work never departed the wall though he walked a fine line between painting and sculpture. (Some of the work reminded me very much of one of my favorite American painters, Lee Bontecou.) His canvases became distorted from the rear instead, pushed and pulled like "knees and elbows," but never free-standing. They were often like bodies, but bodies that had been injured or maimed and could not stand upright on their own. They variously resemble organs, skin, membranes, mucus and sutures. They are also not without landscape attributes -- from the rubble of bombed buildings to the parched earth of Death Valley (now looking much like my front yard.) Emily Braun, the soft spoken but dynamic and talented guest curator says he "attacked" the painting surface, "traumatizing" it.

Grande plastica 1, 1962, Private collection (Plastiche series)

This makes them sound awful. Instead they are astonishingly beautiful. With burlap which he gathered immediately after his return to Italy, varnish and glue, plastics (which resemble what happens when I follow Suzanne Goin's famous recipe for Beef Short Ribs (and the Saran wrap she insists on inside the aluminum emerges burned, holey and dessicated) metal, old nightgowns and paint, he makes each painting an arresting work which on its own would dominate any room, and at the Guggenheim, in profundity makes you jump and shiver with delight.

Credit Davide Gambino and Dario Guarneri, in Italian Alberto Burri: A life in Art, trailer

There is almost a sensory overload by the time you've reached the top and you are quietly grateful for the stark black minimalism that finally appears. By then, Burri was spending a decade's worth of winters in California and was influenced by the minimalism then coming into ascendance around him. His land art in Sicily, recently restored, has also been documented in a film. Burri seems to have predicted just about every trend in 20th century art.

Bianco, 1952, Collezione Prada, Milan( Bianchi series)

He was known to stay out of the way of critics and instead cultivate museum directors. For James Johnson Sweeney, the second director of the Guggenheim who was an early institutional fan and called him the "artist of wounds", Burri made an annual perfect miniature of one of his works as a Christmas present. This display mid-ramp is a seasonal delight.

Sweeney collection of Burri minis

Sweeney collection of Burri minis

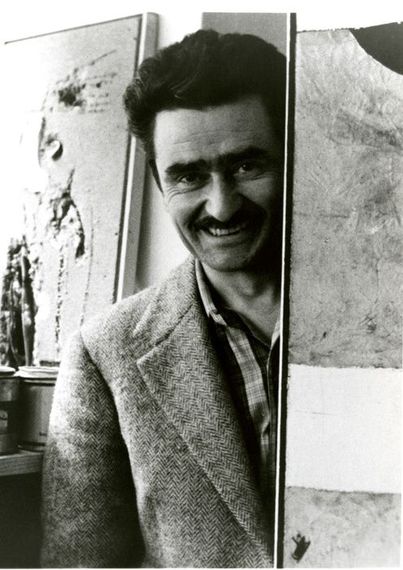

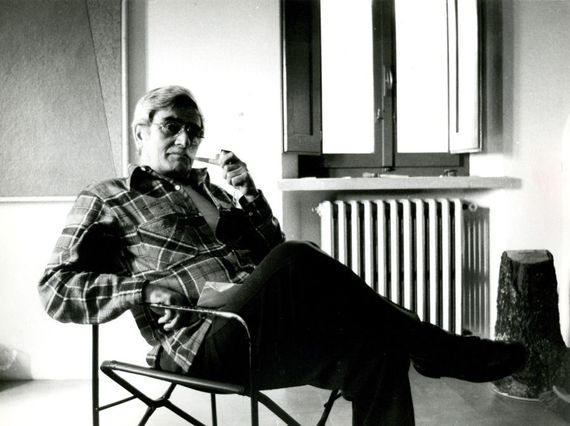

I wondered about the Burri of the Los Angeles years (30 winters) and I was able to speak with Claudio Fogu, a professor of Italian studies at UCLA (site of a Burri black ceramic wall in the sculpture garden) and UCSB, who as a young man came into Burri's orbit and became a friend. They came from the same region in Italy, a region that Fogu says produced 'burberos" -- men who were firmly in the medieval tradition: rough on the edges, short fused, and typically tough on women. Yet Fogu says he also resembled "Geppetto," Pinocchio's father who had a whimsical air.

The youthful and older Burri, courtesy Burri Foundation

His wife Minsa, whom he married in 1955, was a former ballerina, "a striking woman who looked like a porcelain doll... or a Degas sculpture with white skin and lots of mascara" and was herself a 'strong woman, always adamant about her own artistic persona" says Fogu. A "very determined and tense person," she was also a "litigious" person, eventually ending up in a long legal battle with the foundation Burri himself had created for the works. She and Burri were often contentious by day (they each had their own studios in a Ray Kappe-esque house they lived in on the top of Mulholland Drive with views to the Valley) but more agreeable by night. They worked together on a book of her poems which he illustrated. She was insistent on having her own career and to be treated as Burri's peer, and he bought a theater for her in LA.

Burri had gone to Paris and seen Dubuffets and Miros and eventually Rauschenberg and others made a pilgrimage to his studio.

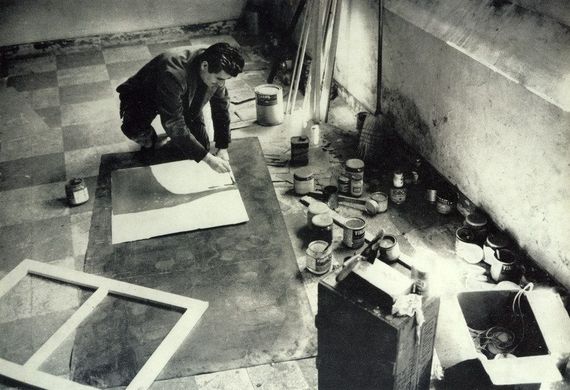

Burri in the studio, courtesy Guggenheim Museum

He saw himself firmly as part of the continuum of art history, even the Renaissance masters from his region whose touches of gold leaf and brilliant reds are echoed in his own masterpieces. Fogu had the impression that Burri was not happy with his place in art history and felt he had been overlooked as one of the masters. Curator Braun qualifies by noting that "all Italian artists of the 1950's, [Lucio] Fontana included, were overlooked in the 1960s in the U.S. by the rise of minimalism." "He was not a joiner and did not seek publicity", she adds. During his lifetime, he actively pursued recognition on his own however (making sure the information about his unusual medical background and as a prisoner of war was known) and bought an old tobacco factory in his hometown which became a museum devoted to his work. In addition, he bought back some of his works, and worked obsessively on his meticulous catalog raisonne. He saw himself as someone who had revolutionized the language of art.

Burri at work, courtesy Guggenheim Museum

It is assumed (though not verified by a doctor) that all the exposures to chemicals and flammable materials eventually took their toxic toll on his lungs -- along with smoking -- and he became severely asthmatic which limited his ability to continue with his work. Burri was a soccer addict and on the weekends Fogu would come and watch with him or help him move or photograph paintings in the studio. He loved jokes and teasing and had a humorous streak.

Burri at work in the studio, courtesy Guggenheim Museum

You will see in this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition one of the clearest examples of an artist marching to his own drum, and in that way, for any creative person, it is a fiery, dramatic, passionate source of inspiration not to be missed.

The Alberto Burri exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum closes on January 6, 2016. Please do not miss the excellent videos on the Guggenheim site.