For many years, especially in the 1950s through 1970s, women artists and writers did their best to keep up with the guys. When the feminist movement came along, they resented being lumped into a category that defined them as "women artists." Why, they had spent their formative, creative lives trying not to be identified as such.

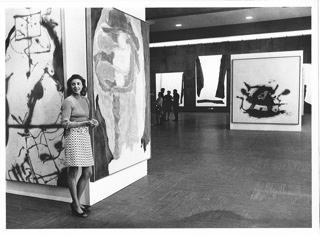

Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, and Grace Hartigan at the opening of Frankenthaler's solo exhibition at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, February 12, 1957. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery and Burt Glinn/Magnum Photos

Writers like Mary McCarthy and Lillian Hellman positively resented what they considered a false and diminutive characterization. They, and many other women who had made their own way without sisterhood, thank you very much, stood intentionally apart from the fray.

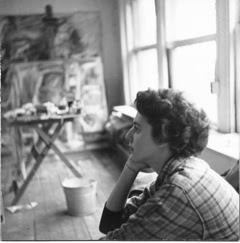

Helen Frankenthaler in her 10th Street Studio, New York, circa 1951-52. Photo credit: Cora Kelley Ward. Courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York

Helen Frankenthaler, a painter who is having a seriously revitalized pop culture moment, was among those who also resisted this label.

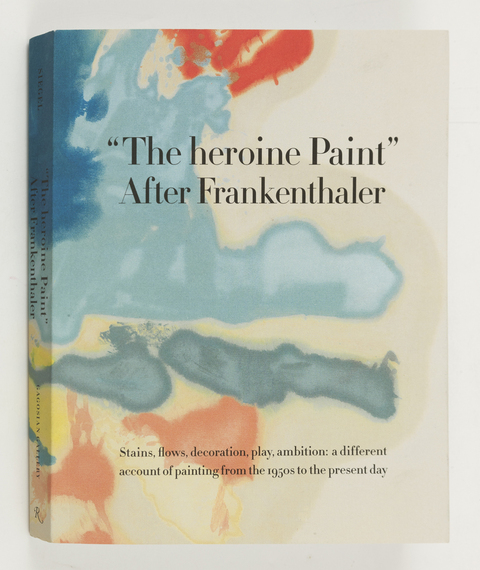

"The heroine Paint" After Frankenthaler edited by Katy Siegel. Cover artwork © 2015 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Rob McKeever.

In a dynamic and excellently illustrated new book with essays about her ongoing influence, "The heroine Paint" After Frankenthaler" published by Gagosian Gallery, the art historian Katy Siegel quotes Frankenthaler in 1964 in response to a question from Henry Geldzahler, then the curator of American Art at the Metropolitan Museum,

"How do you feel about being a woman painter?"

Frankenthaler replied,

Obviously, first I am involved in painting not the who and the how... Looking at my paintings as if they were painted by a woman is superficial, a side issue... The making of serious painting is difficult and complicated for all serious painters. One must be oneself, whatever.

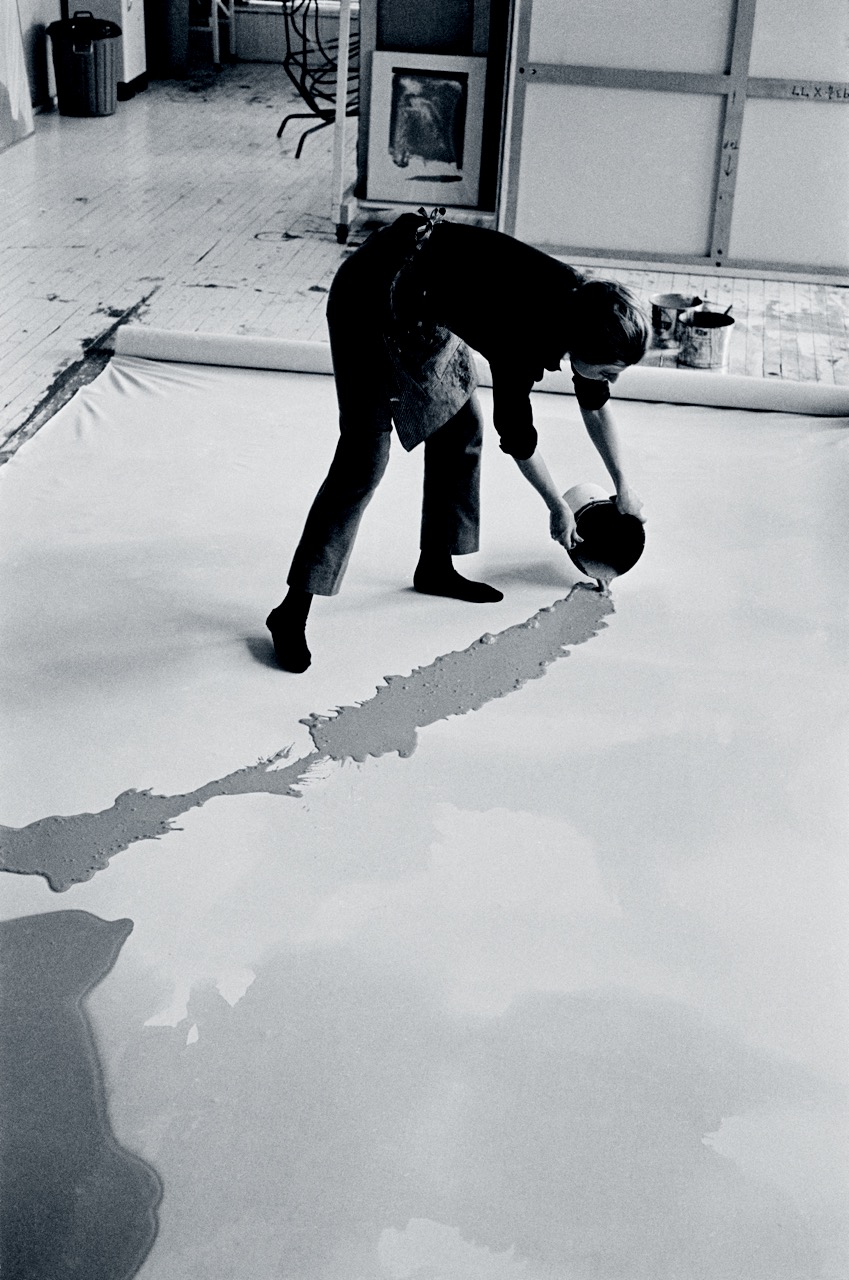

Helen Frankenthaler in her studio at East 83rd Street and 3rd Avenue, New York, with works in progress, Ernest Haas Courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York

Whatever?! Frankenthaler had become a creator of a new kind of abstraction which became known as Color Field painting, using stains and color to seep into the canvas.

Nature Abhors a Vacuum, 1973 © 2015 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York

Her elders, the big boys of Abstraction (Pollock, De Kooning, Rothko, Kline, Still et al) had made their runny, drippy, aggressive marks and Frankenthaler took a different but no less aggressive path to filling the canvas with extraordinary shapes and colors.

Mountains and Sea, 1952 © 2015 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Siegel's book charts Frankenthaler's influence on other (mostly women) artists and their practices. (Some critics have also made analogies to the stain technique being representative of menstrual blood. But this could not help but remind me of Donald Trump). Whether Frankenthaler, who also influenced many other male artists (Morris Louis, Ken Noland et al) would have appreciated this particular collectivity is no longer in my view, relevant: The more women artists and architects can be seen as running towards, rather than away, from their influence on other women artists, the better.

Cool Summer, 1962 © 2015 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Rob McKeever, courtesy Gagosian Gallery

When I went to Elizabeth Hardwick's apartment to interview her at the end of her life about Mary McCarthy, her good friend and colleague, I began by telling her what a role model she had been for me. "I am nobody's role model!" she snapped. I realized I had begun on precisely the wrong note, for she too did not want to be singled out as a woman who had passed along anything particularly "female" or indeed anything other than the caliber of her brilliant work.

In Chicago a few weeks ago at their first architecture biennial, I knew going in I wanted to focus on the women architects -- in a profession seriously deficient in recognition of women practitioners. Though Liz Diller and Zaha Hadid and now Jeanne Gang and Annabelle Selldorf and Kazuyo Sejima of Sanaa have designed towers, I'm still surprised at the number of competitions and short lists that include no women, and equally important, whether those women at the forefront are eager to be role models for other women coming along. The parallel influence and events now swirling around Frankenthaler then, is instructive.

Giant Step, 1975 Artwork © 2015 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Rob McKeever.

In addition to the new Siegel book, a recent exhibition at Brandeis she curated on the School of Frankenthaler was hailed as groundbreaking. Just this week, a symposium on Frankenthaler will take place at NYU Institute of Fine Arts (free and open to the public, few seats remain but the event will be live streamed). Proenza Schouler, the ultra hip design team based their 2015 fall collection on Frankenthaler's inspiration.

Proenza Schouler Fall 2015 Collection

Frankenthaler herself alternated between a sort of intentionally scruffy artist look and a very fashionable one.

Helen Frankenthaler in her studio at East 83rd Street and 3rd Avenue, New York, with works in progress, 1961. Andre Emmerich © estate of Andre Emmerich. Courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York

Helen Frankenthaler at the opening of her traveling retrospective, Kongresshalle, Berlin, 1969. Courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York

A few weeks ago, the Vienna State Opera unveiled their newest safety curtain by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster based on a photograph of Helen in her studio by Gordon Parks (which I don't have the rights to show you here but which you can see online if you go here along with a fab photo of Frankenthaler at the Beaux Arts Ball dressed as Marie Therese Walter, Picasso's young muse and lover).

Copyright: Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster safety curtain at the Vienna State Opera, copyright museum in progress / Andreas Scheiblecker

Speaking of Picasso, and the profound influences females had on him, I often find myself writing about the men, (especially Picasso) and I know part of that perpetuates the iconography of the still influential Great Male Artists. Though Frankenthaler had not been previously been considered by some (male) art historians in that very top rank of 20th century artists, maybe it has as much to do with the way we look at women artists and automatically discount their work. The whole backlash against feminism and women practitioners themselves rebelling against being called women artists or architects should seem antique. Regrettably, it's not.

One of the most interesting things about the book are essays and notes from contemporary women painters themselves on Frankenthaler and her work. Laura Owens, a painter whose work and activism I find admirable, noticed the transitional moment that Frankenthaler herself represented, both foreground and background, messy but who worked wearing her Rolex, who mainstreamed watercolor techniques in her staining methodology. Daniel Belasco points out in his essay, "As Frankenthaler knew, a woman painting in a so-called feminine aesthetic risked gross misinterpretation."

Women artists are still walking that fine line--wanting to be seen as serious players, but also wanting to be able to be feminine without worrying if they will be seen as minor. The camaraderie in the photo at the top is so powerful and showed that there was an early sisterhood of support and though Frankenthaler may have dressed up as Marie Therese, she--and perhaps her fellow artists- were muses for each other. They did not claim feminist labels, but they lived them. As Frankenthaler wrote to Hartigan,

"The pains of beautifully showing your identity are really too much for me sometimes. I never understood the need for muses: come to me!"

Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

To learn more about Helen Frankenthaler, visit the website of her foundation where you can see wonderful images I wasn't able to load and learn more about her work and career.

To learn more about the Frankenthaler symposium this Friday October 23rd and the live stream go here.

To see more of the Frankenthaler inspired Proenza Shouler collection go here.

To learn more about the Vienna State Opera commissioning program and museum in progress programs go here.

To purchase "The heroine Paint" After Frankenthaler go here.