The splendid, evocative Latin American architecture show arrives at MoMA just in time to take the sting out of the bad press for their Bjork show. Although it's been in formation for six years, it hits the wave of resurgence for all things '60s and '70s and shows when its on its true game, there is nothing better than MoMA.

The exhibition attests to the "the region's breathtaking pace of change, modernization and shift toward the metropolis" says Barry Bergdoll its chief curator and editor of its massive catalog.

Borchers/Suarez/Bermejo Artists Studio 1940

Instagram-friendly (#ArquiMoMA) in 11 designated cities, laden with historic film clips (courtesy the excellent work done by Joey Forsyte), beautifully rendered colored drawings, newly commissioned models, period photographs and wall text, the exhibition will impress some as an historical exhibition, quite similar in vibe to many of the pavilions at this year's Venice Architecture Biennale which looked back to this same period and which also relied on abundant use of film to contextualize and seduce the average viewer. To my mind the large gray expensive newly constructed models serve less well than the films as at a certain point, drawing and wall label fatigue inevitably sets in and the films provide an important pivot to the actual use of the structures.

But Bergdoll and his team of invited co-curators and staff have a larger mission: They mean to correct the oversight of the impressive Latin American modern architecture of 1955-1980, a period which saw the rise of many talented men (and a very few women) and stop the trickle-down and encourage the trickle-up.

My own experiences with this period began on a trip to Rio as a young teenager on an exchange with a Brazilian family whose daughter then came up to suburban New York. Obviously I got the better end of the deal. Going from a modernist house in Botafogo to a glass house in the mountain enclave of Petropolis above the city, dancing all night on Ipanema beach in front of the tall hotels lining the beach, was a jolt for a girl reared in a small split level in one of the many suburban developments which had sprung up around New York City. The exhibition brought back the thrill of heady freedom and the future.

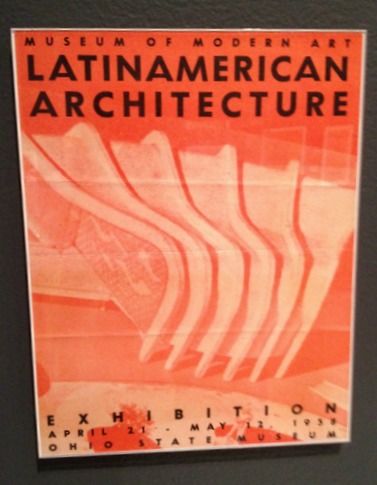

Poster for the Latin American Architecture exhibition MoMA 1958

One of many jobs I soon held at MoMA was in the special events department and I had to lay the sand filled bags of candles that would light the way to the parties in the Garden that was then filled with vitrines specially made for the Italy: the new Domestic Landscape show that anointed that countries original design output. Though this exhibition is meant to recall MoMA's earlier landmark show of Latin American design in 1955 it was in fact the Italian show that it recalled for me: the undulating shapes, the innovative fenestration, the attempt to meld outside and inside, the modernist ethic being overtaken by generous new thinking -- and the influx of so many talented architects in NY. That show curated by Emilio Ambasz; this one partially funded by his generosity.

Tatiana Bilbao alongside Eduardo Terrazas. Triennale di Milano, Mexican Pavilion. 1968.

Walking through the exhibition with the Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao who self-identifies as a "rebel"--she does not design on computer but by writing and models and civic engagement--gave me another hands-on perspective. Bilbao, one of the leaders of the new wave of Mexican architecture that also finds inspiration from a populist point of view, was as stimulated as I was to see these original structures and projects joined together and made sense of as a movement.

"In architecture school," she reminded me "we never learned about this. Our focus was global, to move forward."

An admittedly small survey of leading American architects of a certain age I made also showed that North American architecture students learned precious little about Latin American practitioners. Things have not changed that much. Of Bilbao's mostly final year grad students at Yale this semester none had been to Mexico (she remedied that last month) and only one other Mexican (Enrique Norten) has been invited to teach at Yale. We together bemoaned this huge gap of information about Mexico -- hearing mostly about gang warfare, missing murdered children, immigration... and the best beaches.

Is this exhibition just an exercise in nostalgia or newly hip sixties and seventies fashion? I think not. What the Latin American show demonstrates unequivocally is the necessity of political and social ideas to meld with architecture to produce innovation. Public structures are thus the unifying theme between the countries themselves -- universities, housing, skyscrapers -- the civic sector. The state was most often the muscle behind the project funding. Banks were the other deep pockets; they also wanted to make modern impressions, for example Clorindo Testa's spectacular Bank of London in Buenos Aires.

Clorindo Testa. Bank of London and South America, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1959-1966. © Archivo Manuel Gomez Piñeiro, Courtesy of Fabio Grementieri

This emphasis on the indigenous and away from roving starchitects is certainly appealing and hints that the way forward should be inclusive of one's own country's rich architectural heritage. Bergdoll aims to show " the conversations between countries"and above all the integrity and innovation of the Latin American architects. This, he postulates, was not a case of them bowing at the temple of Wright, Corbusier and Mies, though evidence that those architects did influence their younger colleagues is presented. Rather it is to demonstrate the originality of the nativist impulse and its eventual international export. (Over and over however, I was reminded of Paul Rudolph's work as well as Louis Kahn's.) The early adopters of this New Wave were Mexico and Brazil as there was a critical mass of talented thinkers who congregated in these two countries and governments to back them up. Other countries are also well represented -- Cuba, Argentina, Colombia, Venezuela, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, the Dominican Republic and even Puerto Rico. This is another post-mid-century modern, not the one defined by our American heroes (Eames, Nelson, et al) but by Costa, Burle Marx, Bo Bardi, Barragan et al, names we know and others Reidy, Villaneuva, Pani, Alvarez, Testa, we're only belatedly beginning to recognize. (There is even Alejandro Zohn, author of the wonderful Mercado in Guadalajara, no relation that I'm aware of but hopeful!)

Juan Sordo Madaleno. Edificio Palmas 555, Mexico City, Mexico 1975. Photo Guillermo Zamora. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Sordo Madaleno Arquitectos

Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer. Plaza of the three powers, Brasilia, Brazil, 1958-1960. Photograph: Leonardo Finotti © Leonardo Finotti

Brasilia, the capital created out of whole savanna cloth by Oscar Niemeyer, Lucio Costa, Burle Marx and their compatriots in 1960 stands out, a massive achievement that still has people shaking their heads at the hubris of relocating an entire capital city. Obvious precursors are the Mexican and Venezuelan university cities which were responding to enormous growth and political change(there are now 300,000 students in the Mexico City university). The architecture and planning sprang from the amplitude of land as much as the void of local solutions to the urgent needs of the bourgeoning population. And a supply of cheap labor. As Bilbao reminds me, "Europe was finished, there was nowhere else to go." She bemoans the fact that there is still no animated street life in Brasilia, however. "This is the problem of this kind of development."

Oscar Niemeyer. Cathedral Under Construction, Brasilia, Brazil. Photographer: Unknown. Arquivo Publico do Distrito Federal

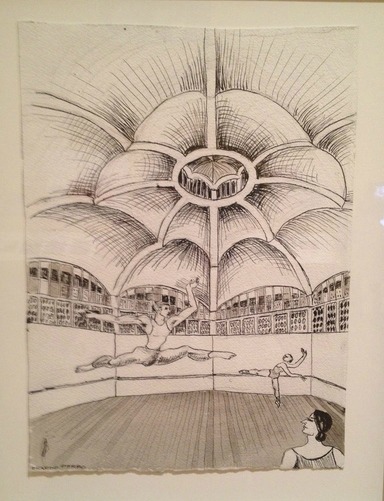

Seeing the show after a recent trip to Havana made everything more vivid especially the deteriorated condition of one of the most ambitious projects in the exhibition, the Cuban National School of the Arts. A playful drawing of the ballet pavilion by Roberto Porra as it was designed for Alicia Alonso's ballet company stands aside my snaps of that particular building, sadly empty, mired in mud. Once the Cubanacan Country club reclaimed by Castro along with the rest of the rich neighborhood, it became a victim of neglect and regime priorities as well as Alonso's mysterious disaffection. I heard a rumor that Norman Foster had volunteered to wave his magic wand over this historic Riccardo Porro/Roberto Gattardi/Vittorio Garatti brick project and I just pray that one of the young out of work Cuban architects I met instead have a chance to restore this icon of Cuban architecture. If anything demonstrates the folly of Latin America needing to look outward for its new buildings, it is this exhibition.

National School of the Arts, Havana 2015 Photographs by Patricia Zohn

National School of the Arts, Havana 2015 Photographs by Patricia Zohn

National School of the Arts, Havana 2015 Photographs by Patricia Zohn

National School of the Arts, Havana 2015 Photographs by Patricia Zohn

National School of the Arts, Havana 2015 Photographs by Patricia Zohn

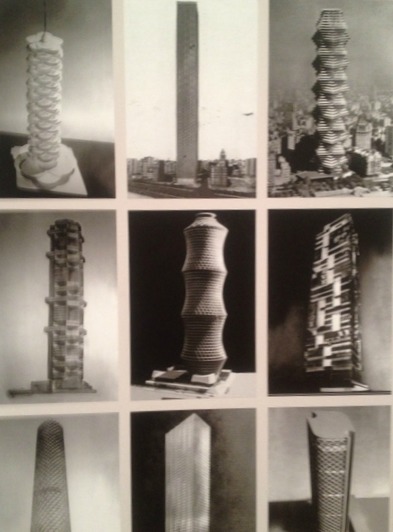

One need only look at images of the buildings submitted for the 1961 Peugeot competition to build a skyscraper in Argentina to see a much earlier version of a Norman Foster Hearst Tower, a Renzo Piano London Shard, a Thom Mayne Phare tower.

Entries for Peugot Skyscraper competition, Argentina, 1961-2

The Jose Marti memorial tower in Cuba, designed by Varela and built 1953-8 and also generated by a Cuban competition is of a piece with these other Peugeot entries, none which were ever built.

Jose Marti Memorial, Havana by Varela 1953-8 Photograph by Patricia Zohn

The largely prefab Russian architecture of Cuba, the outlier in both location (mostly outside the main city of Havana) has not garnered the affections of most architectural historians. But I was instantly struck by the Russian towers and smaller storage structures and housing which have a concrete integrity and especially those that D'Acosta who was able to adapt them to Cuba. Havana has been lucky. No money has meant no architecture destroyed -- even if much is in sadly deteriorated condition.

Havana Private Home, 2015 Photograph by Patricia Zohn

In contrast, Bilbao pointed out many of the buildings which no longer exist in Mexico. (Bergdoll and co would be doing us all a great service by loading a directory of buildings that do exist and how best to access them). Utopia turns out to be a fungible proposition.

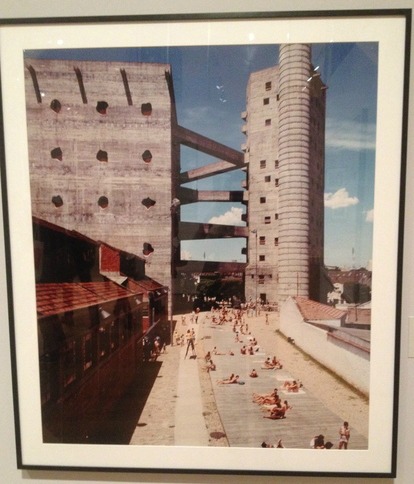

Lina Bo Bardi Romulo Fialdini SESC Sao Paulo, 1977-1986

Women's work is sparse: Lina Bo Bardi, born Italian but eventually a Brazilian citizen, is one of only two women in the show, the other Elsa Mahecha, a Colombian who co-designed a beautiful art museum with Alberto Estreda and a science building at the University in Bogota. This is not the fault of the curators, but rather just the way it was (everywhere!). Bilbao says when she first saw Bo Bardi "it was a revelation and a great inspiration".

Lina Bo Bardi

Elsa Mahecha/Paul Beer Museum of Natural Sciences, Bogota, 1972

Five great ways to complement this landmark exhibition (short of traveling to see the extant buildings):

1- Read Elizabeth Bishop's poetry and watch the film Reaching for the Moon by Bruno Barreto available on Netflix. Bishop went to Brazil to get away from herself and sadness and found happiness with designer Lota de Macado Soares whose fabulous home, pictured in the film says so much about the time. Soares designed Flamengo Park in Rio but after the project became mired in overruns and politics was betrayed by Roberto Burle Marx whom she had hired as landscape designer.

2- A recent documentary by the son of Sergio Bernardes who is represented in the exhibition. MoMA should also program it, but in the meantime look for it in limited festival release.

3- See the films of Brazilian Nelson Pereira dos Santos which are in retrospective at MoMA from April 9-17.

4- See the small but lovely Americas Society Design show to get a feel for what was going on in domestic interiors at the time.

5- See Under the Mexican Sky, the wonderful LACMA exhibit that has now traveled to the Museo del Barrio about Gabriel Figueroa the director and cinematographer who worked with Bunuel and John Huston but who was an auteur of astonishingly beautiful images of Mexico in his own right. He truly painted pictures with his camera.

This view of our nearest neighbors to the south emerges as a timely reminder, another candle to light the way, not just for architecture but for the enormous creativity of so many Latin American artists we have yet to give their due.