Dáithí de Mórdha works as an archivist at Ireland's Great Blasket Centre, located in Dún Chaoin, on the tip of the Dingle Peninsula, at the halfway point of the Slea Head Drive. The Centre is an interpretative facility and museum detailing the unique community who once lived on the Great Blasket Island, their traditional way of life as subsistence fishermen and farmers, as well as the extraordinary amount of literature which the islanders produced.

Daithi gave me a tour of the Blasket Centre and an education on what life was like for its residents and those who emigrated from the island. He offers some fascinating insights into a slice of Irish culture and history and what it means to be part of a landscape--as well as to need to leave it behind.

Meg: Can you describe the location of the Blasket Islands?

Daithi: The Blaskets are a group of islands situated on the west coast of Ireland, at the tip of the Dingle Peninsula in Co. Kerry. They range in size from less than an acre to the 1,000 acres of the largest one, the Great Blasket. The islands are only one kilometre from the mainland, but the Blasket Sound between them and Dún Chaoin is one of the most treacherous stretches of water in Ireland. It is often the case that the island is cut off from the mainland, even with modern boats and helicopters, for weeks due to adverse weather conditions.

Meg: The Island has a great literary tradition...can you explain the background to this?

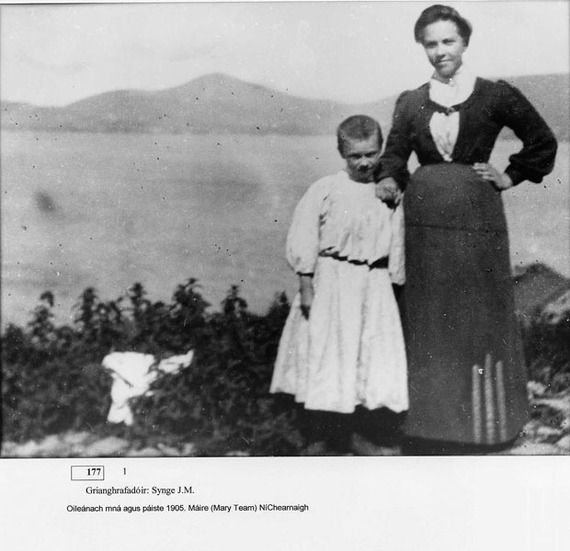

Daithi: At the turn of the 20th century there was a revival in interest and study of the Irish language. Scholars from Ireland, the UK, Europe and Scandinavia began venturing to the most remote, Irish-speaking communities to study the living language. Many went to the Blasket, and encouraged the people to begin writing accounts of their lives. In the 1920s and 1930s the Blasket Island writers produced books which are deemed classics in the world of literature. They wrote of Island people living on the very edge of Europe, and brought to life the topography, life and times of their Island. They wrote all of their stories in the Irish language. The term 'peasant literature' is sometimes used for this type of literature, but I find that disparaging; I think the Irish term 'Litríocht na nDaoine' (The People's Literature) is better.

Meg: The Centre's film on the Island's history said that residents had a name for every field and every cove. I found that very moving. Could you elaborate on this?

Daithi: The majority of the islanders who didn't emigrate rarely ventured more than 20kms for the island. Therefore their worldview was based on that which was familiar to them. We, as citizen of the global village, can name cities, mountain rivers etc from all over the world. The islanders had a name for every feature of their islands because the islands were their whole world. Also as fishermen and farmers they needed to be very specific as to where things were located. Many of the placenames were practical (An Ghort Fhada, the long field, for example), but others had more deep meanings, like An Leaca Dubhach, (the sorrowful slope), so named because of a fishing tragedy which left 18 widows as a result of so many men being drowned.

Meg: Can you talk a bit about the significance of fishing to the Islanders?

Daithi: People who don't live by the sea can see the water as a boundary which stops you from doing something. For coastal peoples the sea is a highway - for the Blasket Islanders, they were only a few days old the first time they travelled by boat, to come to the mainland for baptism. From then until they died (they also were buried on the mainland), even the most simple things required sea travel - shopping, church, hospital & doctor visits, even going to dances or football matches. Thus the sea was central to every aspect of their lives.

Meg: Can you explain why the relocation occurred?

Daithi: The island was officially evacuated by the state on the 17 November 1953. The main reason for the evacuation was emigration; from a peak of 176 in 1916, the numbers fell to just 21 in 1953. Generations of young people left, leaving the majority of the island's population as either old couples or middle-aged bachelors. There was only two weddings on the island between 1930 and 1953. If you take away the young people from a community, you take away the future, and without new children being born, the island was doomed.

Other factors included the closing of the island school in 1941, again due to a lack of schoolchildren, the lack of facilities such as a shop or church, and the death during the winter of 1947 of a young man, Seáinín Ó Cearna, of meningitis, without the aid of a doctor or priest due to severe weather conditions. This was the straw that broke the camel's back for the island; the people asked the government for help, and after a lengthy period of investigation, they decided to give the islanders new farms and homes on the nearby mainland. The islanders, by this stage, wanted to leave; many of them were afraid of meeting the same fate as Seáinín.

Meg: The Springfield/Holyoke area of Massachusetts, where my family is from, was the primary destination for emigrants from the Blasket Islands. Can you describe what inspired those waves of immigration?

Daithi: A young woman on the island had a choice to make when she reached 17/18 years of age. She could either stay on the island, hope for a marriage, struggle with housework, farmwork, raising children etc, or emigrate. There was no other employment on the island. The women were especially envious of the lives their aunts, sisters and friends were living in the US, with nice shop-bought clothing, steady employment, cars and houses, running water etc.

The economic effect of this was not as severely felt as the emotional effect: most emigrants sent home money to their parents and the letter and parcel from America was keenly awaited for. But the emotional effect was massive; the vast majority of emigrants up until the 1950s rarely returned home, even for a visit. Emigration was like death - you were not likely to see that particular relation again. A case in point from my own family: my grandfather had a brother whom he never met, because his eldest brother had emigration before my grandfather was born and never came home.

Want to hear more? The complete interview is here. Want to see more? The pictures are here.

Meg Pier's www.ViewfromthePier.com features an extensive collection of "Peer to Pier" interviews with fascinating folk from around the world.

Become a Fan of View from the Pier on Facebook www.facebook.com/viewfromthepier