David Lynch's first museum retrospective in the U.S. is in Philadelphia, with good reason. "Fear, insanity, corruption, filth, despair, violence," the filmmaker told reporters Wednesday, all hung "in the air" when he was a student there in the 1960s.

The matter of Philly's darkness permeated this introduction to the exhibit, David Lynch: The Unified Field, which opens at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts this weekend. Figuratively and literally: Not only was Lynch's home broken into thrice in those days (he was a PAFA student when he made much of the work in the show), but even visually, "every building was black," he said.

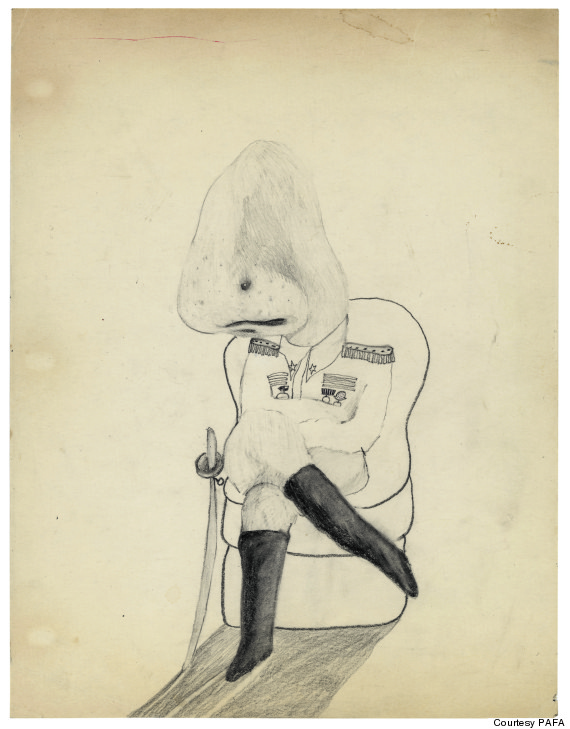

An untitled work by Lynch, painted in 1971.

A "soot-colored" landscape burrowed into Lynch's psyche. Palm trees and noir may mark his best known films (for example, Mulholland Drive and Blue Velvet), but "no place," he said Wednesday, "has influenced me as much as Philadelphia."

"It was very pure, very filthy," he said, before adding with a chuckle: "It was so beautiful to me."

Lynch is an unexpected ham, as anyone who watched the third season of Louie knows. He dresses in black and would fit right into any of his own macabre movies, but he's far from self-serious. His counterintuitive statements come with a wry smile, and the effect is transformative. Suddenly, he's your grandfather letting you in on a joke. You feel you understand him more than you did before. (At the "beautiful" line, the audience laughed knowingly -- dutifully -- along with him.)

Of course, he is not your grandpa or anything like him. Lynch's paintings -- the subject of the exhibit -- are flecked in band-aids and cigarette butts. The one everyone's talking about, Six Figures Getting Sick (Six Times), involves plaster casts of his own, younger, head, onto which animations of vomit are projected to the tune of sirens. These are among his earliest works. Before Lynch ever touched a camera, he was a classical artist, an advanced painting student at PAFA. His interests soon expanded to a concept he describes as a "moving image." His first experiment in this realm was Six Figures, which is on display for the first time since it showed in Lynch's student days (in the room used Wednesday for the press conference) and won him a prize. A minute long and strangely affecting, the audiovisual experience could reasonably be called a proto-film.

Lynch paints to this day. He describes the activity as a narrative exercise. Humanoid figures populate his works. Sometimes they are decapitated, or fleeing monsters. "I like to think of a little story in a world," he said Wednesday, on his approach to painting. "Maybe a few frames before the one you see, and a few after."

For "I Burn Pinecone And Throw In Your House," Lynch incorporated the materials of the narrative: pinecones and matches.

The concerns of these works -- insects, decay, danger -- also haunt his filmography. One of the burglaries at Lynch's home in Philadelphia occurred while his young family slept. The experience stayed with him, notes PAFA's senior curator, Robert Cozzolino, who worked closely with Lynch on building the show with the help of friends in the area for whom a young Lynch painted for cash. Nowhere is safe in a Lynch film, and fixations include "domestic interiors, and what happens to the body in stressful situations," as Cozzolino delicately described the Lynchian aesthetic Wednesday.

Elevating human misery to art inevitably yields questions. A local reporter brought up the Philly neighborhood dubbed "Eraserhood" after Lynch's "Eraserhead." The area, which Lynch used to live in, has since been "ruined," the director said.

"So it's a little nicer, therefore ruined?" asked the reporter.

"Yeah," Lynch said, the little smile back.

Why did the old danger so enthrall him, another asked? Lynch admitted to not knowing exactly why, except that "it just gave a lot of ideas." The dark energy became "a fuel" still "percolating inside me."

The tale of the artist and the underbelly is not a new one. Look at Detroit today. Prices are cheap, tragedies play out on the street, and artists are moving in. Such a place is "cut off," Lynch said. "When I was here, Philadelphia was this lost, remote corner of the world. People had a certain way of dressing, a certain music they listened to."

The philosopher John Dewey famously defined art as a manifestation of daily experience. So too might Lynch. He claims to know little about the history of art or film, out of disinterest. "I'm not proud of it, but I don't care about what happened yesterday, really."

Disconnection arguably keeps the horrors of modern life fresh. Case in point: Lynch's first night in Philadelphia, "I saw a TV," he told the audience, as if describing a meeting with an alien. (He watches television rarely, he added, mostly when traveling.)

"It was a story about a man who hit a woman in an elevator," he continued. "Hit her so hard she fell down."

The man is almost certainly NFL running back Ray Rice, whose abusive behavior is all over the news right now. Lynch detailed a little more: about Rice dragging his fiancée from the elevator, and "plopping" her to the ground, as he put it. He spoke wonderingly, as if we'd switched tracks into a parallel world in which none of the press corps knew the awful facts. Into the rhythm of a press conference, here was suffering. We halted into a moment of silence. A reporter eventually broke it, venturing: "It's like a scene from one of your movies."