If you go to 36 Lispenard Street, in New York's Tribeca neighborhood, you will find a plaque erected by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The plaque honors the work of the people who, during the time before slavery was abolished, helped shelter women and men who were escaping from the horrors of the South. The house served as a crucial station on the Underground Railroad; the LPC estimates that over 1,000 slaves passed through its door.

The plaque specifically mentions a man named David Ruggles, a remarkable figure in the history of New York City, journalism and the epic, heroic battle that abolitionists fought to defeat the scourge of slavery.

Ruggles' story is incredible. Born in 1810 in Connecticut, he became a fearless and tireless campaigner against slavery and discrimination. A century before Rosa Parks, he deliberately sat in the "white" section of a train, and then sued the railroad company when he was thrown off.

Ruggles became one of the prime leaders of the New York Vigilance Committee, an anti-slavery outfit which was headquartered at 36 Lispenard. Their exploits were wildly risky, and very courageous, as Ruggles' biographer, Graham Russell Hodges, recounts:

Ruggles and the rest of the Committee of Vigilance openly confronted slave catchers, demanded that the city government grant jury trials to fugitives and offered legal assistance to them. Backed by the New York Manumission Society, whose members included the lawyer William Jay, son of Chief Justice John Jay, the Committee of Vigilance proved highly effective in protecting the rights of local blacks. On several occasions, Ruggles went to private homes where enslaved blacks were hidden and informed the servants that they were actually free. In case anyone missed these activities, Ruggles often published such adventures in abolitionist newspapers such as the Emancipator and The Liberator.

Ruggles himself estimated that he helped over 600 slaves on their way to freedom. As part of his efforts, Ruggles took in a man who had just escaped from slavery in Maryland: Frederick Douglass.

Douglass tells the story in his autobiography, "My Bondage and My Freedom":

I kept my secret as long as I could, and at last was forced to go in search of an honest man -- a man sufficiently human not to betray me into the hands of slave-catchers. I was not a bad reader of the human face, nor long in selecting the right man, when once compelled to disclose the facts of my condition to some one.

I found my man in the person of one who said his name was Stewart. He was a sailor, warm-hearted and generous, and he listened to my story with a brother's interest. I told him I was running for my freedom -- knew not where to go -- money almost gone -- was hungry -- thought it unsafe to go the shipyards for work, and needed a friend. Stewart promptly put me in the way of getting out of my trouble. He took me to his house, and went in search of the late David Ruggles, who was then the secretary of the New York Vigilance Committee, and a very active man in all anti-slavery works. Once in the hands of Mr. Ruggles, I was comparatively safe.

Douglass adds, "[Ruggles] was a whole-souled man, fully imbued with a love of his afflicted and hunted people, and took pleasure in being to me, as was his wont, 'Eyes to the blind, and legs to the lame.'"

But Ruggles was also a groundbreaking figure in American journalism, as Hodges writes:

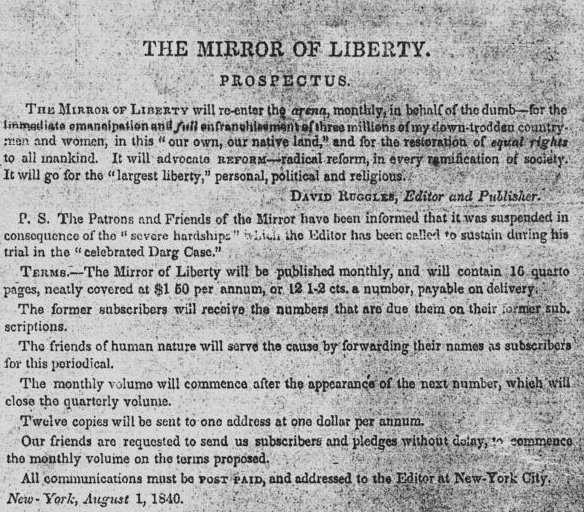

In addition to his service as the key conductor of the Underground Railroad in New York City in the 1830s, Ruggles was a tireless, fiery, pioneering journalist, penning hundreds of letters to abolitionist newspapers, authoring and publishing five pamphlets, and editing the first African American magazine, The Mirror of Liberty.

Here's what the first issue of The Mirror of Liberty, published in 1838, looked like:

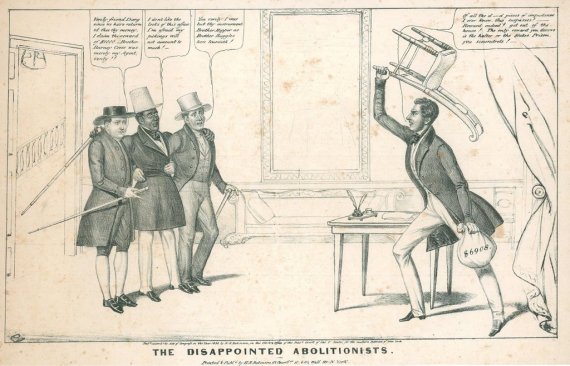

Unsurprisingly, Ruggles' high public profile made him a controversial figure. In 1838, he was arrested and indicted, along with three associates, after he refused to return a slave to his owner. It was a sensational case, enough to make him a subject of political cartoons like this one:

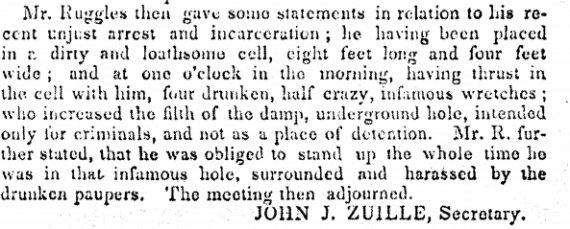

Ruggles was undaunted. Here is an account he gave of being arrested:

Ruggles continued his activism, but he was plagued by severe health problems. In 1842, he moved to Massachusetts, where he became a doctor. He died in 1849.

In 1841, Ruggles gave a speech in Boston. In it, he said:

I have had the pleasure of helping six hundred persons in their flight from bonds. In this, I have tried to do my duty, and mean still to persevere, until the last fetter shall be broken, and the last sigh heard from the lips of a slave. But give the praise to Him who sustains us all, who holds up the heart of the laborer in the rice swamp, and cheers him when, by the twinkling of the North Star, he finds his way to liberty. Six hundred in three years I have saved; had it been in one year, I should have been nearer my duty, nearer the duty of every American, when he reflects that it was the blood of colored men, as well as whites, which crimsoned the battle-fields of Bunker Hill and the rest, in the struggle to sustain the principles embodied in our Declaration of Independence.

As this year's Black History Month draws to a close, it's worth remembering such an unsung hero.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article misstated Hodges' middle name as David. His middle name was Russell.