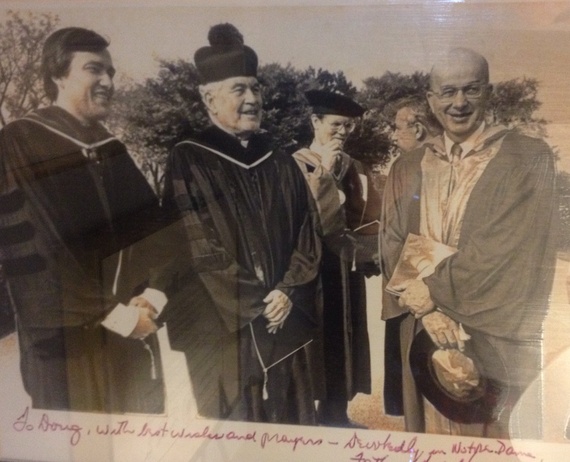

Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., the long-serving ex-President at the University of Notre Dame died last week. Father Ted, as he was affectionately known, gave me the privilege of teaching at Notre Dame for nearly 20 years. His friendship transformed and shaped my life.

In spring 1980, I saw the famed golden dome for the first time. I had never seen a more beautiful campus and I felt immediately welcomed by mother Mary's open arms atop the dome measured against a bright blue sky which would prove to be a relatively rare sunny day in South Bend, Indiana. On the leeward side of Lake Michigan, Notre Dame sits astride the Indiana toll road and this modest Midwestern town that in the summer is drenched in humidity and populated by evening mosquitos that easily could walk on to the Irish travel squad. The only thing worse than summer in South Bend is fall, winter and spring, which except for a few fine days in October merge into steel grey overcast as a capstone to mounds of "lake effect" snow which stubbornly overstays until graduation week in May.

No one chooses Notre Dame for the weather.

Technically, according to Father Ted, I was an hour late the day of my first visit. Lateness is one of my most troublesome vices, though I have been working on others. In fact, it is easy to arrive late because somewhere near LaPorte to the east --- where Chief Justice Roberts attended high school - a small sign appears on the side of the toll road: "Entering EST." Having lived in California to attend law school at Notre Dame's arch rival, USC, I of course thought "est" referred to training seminars that originated in San Francisco and became highly popular with celebrities. The seminars which urged the stripping away of societal masks and impositions in favor of one's real self were often described as "transformative," the same word I used above to describe Father Hesburgh's intervention in my life.

Unfortunately, a few miles down the road a closer look at the flat farmlands still strewn with piles of highway brown snow suggested a different meaning of "est," than mind-blowing California tricks to spark our hidden potential When Father Ted pointed out my ostensible tardiness, I gave a smiling, but strong rebuttal that the appointed hour did not specify my time or his. Surprisingly,FatherTed who was not used to being corrected --- even with a friendly quip - laughed out-loud, and from that moment I felt I had reconnected with an older brother.

Observe Father Ted for a few minutes and you see him reaching out to encourage everyone in his path from a member of the maintenance staff to a well-heeled CEO to an academically accomplished Ivy-league or Oxford scholar petitioning for employment. Not that Hesburgh was always strolling the footpaths around the two campus lakes; indeed, various student comediennes would ask: "what is the difference between God and Father Ted?" And the response," God is always on campus, Father Ted seldom is." That was overstatement. Hesburgh served every President since Eisenhower on tough minded commissions dealing with civil rights and immigration, in particular. Obviously, our dysfunctional Congress could use Father Ted's optimism right this budgetary-impasse moment.

Hesburgh's savvy and determination mirrored that of another priest --- the first president of Notre Dame, Edward Sorin C.S.C. Sorin was an entrepreneur - he built homes nearby so the rural university did not have to await city formation, arranged for a post office to deploy university catalogues, and more. Hesburgh's relations with his French order (the Irish moniker being derived from a sports-writer who bemoaned an under achieving football squad, describing them as "Irish and not even fighting.") Sorin built the university over the skepticism of his religious superior. Actually, he built it twice - the second time after a devastating fire destroyed the first golden dome, which would have devastated a normal man, but was accepted as a Marian challenge by Sorin. "Mary simply wanted something nicer and bigger," said Sorin to his astonished brothers in the French order. In a record nine months the university was rebuilt leaving an expression still used on campus to signify a like challenge: "there is blood in the bricks."

These stories had not yet been passed my way when I arrived at Notre Dame that spring day 36 years ago. I remember well the physical allure of the campus, however. I was overwhelmed by the campus: its serenity, its sweetness, and more metaphysically, what I would come to realize later, its hope premised upon a sublime faith and self-confidence that pours out each day with a positive cheerfulness that seems oddly dissonant with world events with which Hesburgh ensured student engagement.

Pulling up to the front entrance known as the circle, a robust young man of Italian ancestry named Gus approached and asked my business at Our Lady's University. "Your dean has requested that I apply for a teaching position," I said

"Really now," the skeptical young man said," eying the USC Trojan sticker affixed to the back window of my old Toyota. "Some," opined Gus in his "Jimmy Cagney-like, distinctive south Philly accent might see that sticker as "fighting words." The term of art used in First Amendment analysis gave Gus away as a law student. Nevertheless, keeping up the pretense of playing the choir boy in the classic Bing Crosby movie, "Going my way," Gus pronounced my sentence: "pray and ask forgiveness," and he continued: "be prepared with a good answer for your wandering beyond the fold."

The latter would prove to be providential advice for the interview process -- which in my case proceeded over three visits and several days. Having convinced the students, faculty, and board members of my Catholic sensibility and knowledge of the law, the final question was put to me in the Civil Rights Reading Room which then served as an archive for Father Ted's work with the US Civil Rights Commission. Ted would later reveal that he was "fired with enthusiasm by Richard Nixon" from the job since Hesburgh had the fortitude to hold the Nixon administration accountable for some lackluster compliance of its own. Father Ted's public service was shaped by his commitment to high principle, a course made easier, Father recounted by the pleasant thought of returning to ND. He urged me to keep the open door at ND in mind and act in like manner. When an assistant secretary attempted to subvert the mission the President gave me publicly to build up our inter-faith understanding and diplomacy, I did indeed keep this good advice in mind.

Oh yes, the final question put to me in the interview for the faculty: "What team would I support in the rivalry? Having been admonished by Gus to be prepared to explain my football apostasy, I responded: "I intend to sit proudly on the Notre Dame side and pray silently that SC looks darn good."

Laughs and a welcome aboard.

By the time of my arrival, Father Hesburgh had already transformed Notre Dame into an undergraduate institution matching the Ivy's and schools like Northwestern and USC from which I matriculated. Now Father Ted sought something grander: affecting the entire faith by disapproving of and disproving the stereotype that the intellectual side of the Catholic faith is no deeper than the memorized Baltimore catechism.

In the 1950s, Catholicism was not widely perceived as possessing the intellectual grit for empirical discovery. In Rome, a simple Italian prelate by the name of John XXIII was reawakening Catholic liturgical life in a conclave known as Vatican II which changed the Church around the globe . By the time Father Ted was completing his extraordinary 35th year as president, however, Notre Dame had become the beating heart of a faith that had found its voice in the pursuit of social justice. Father Ted's national presence with Martin Luther King in behalf of civil rights exemplified this of course, but it was also the very talented and earnest young men ( Hesburgh opened the school to women in 1972 in league with many other institutions), and while Notre Dame women can recount the usual male stupidities, their critical thinking and academic competitiveness was never doubted, as Larry Summers would let slip at Harvard. Hesburgh inspired students to act, not just read the Gospel.

In the 1960s, a youthful, idealistic, Kennedy-esque mindset brought Notre Dame graduates like Fernand "Tex" Dutile down to the south on Freedom rides. In the 1980s, Margaret Ryan would rank #1 in a very competitive law class, marry Michael Collins (#2), fulfill with distinction her duties to the US Marines, including trial litigation service in Okinawa at a very sensitive time and ultimately as aide to the Commandant. Today, Professor Dutile is just beginning a well-deserved retirement after four plus decades in the classroom, including a stint as Dean and a long-time member of the NCAA body overseeing the integrity of college sports. Judge Margaret Ryan is a revered member of the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Services. If column length were without limit, the Hesburgh-inspired graduates who devoted a substantial part pf their lives to the Peace Corps, AmeriCorps, Teach for America, and like organizations and endeavors would include just about all those who were academically able to study there.

Bottom line: In the 1960s and 70s when the rest of the US, if not the world, started a deconstructive march through self-indulgence, Father Ted was insisting on strategic thinking that made a good faith effort to reconcile orthodoxy and intellectual inquiry. Then, and now, many were/ are dissatisfied with Ted's Land-o-lakes rapprochement of faith and reason (and the ecclesial relationship between university and the local bishop), but Father Ted took the criticism in stride. "Come here, help us do better," he would challenge his critics, whom he not infrequently brought onto his faculty. One such opponent was the distinguished editor of the American Journal of Jurisprudence - formerly, the Natural Law Journal, Professor Charles E. Rice. Rice died within hours of Father Ted last week. Rice was a tough, but much beloved instructor not only of law, but also, by virtue of his reserve status as a Lt. Colonel in the Marines, boxing. In terms of Catholic developments, Rice was about as right as Hesburgh was left. Rice was nationally respected as a pro-life advocate; indeed, whine carefully examined, Rice was the only Catholic pro-life activist who took a position consistently in favor of protecting life, including unborn life, in all circumstances even when doing so would run counter to saving the mother or where the pregnancy was the result of rape.

Rice died within hours of Father Ted last week. Rice was a tough, but much beloved instructor not only of law, but also, by virtue of his reserve status as a Lt. Colonel in the Marines, boxing. In terms of Catholic developments, Rice was about as right as Hesburgh was left. Rice was nationally respected as a pro-life advocate; indeed, whine carefully examined, Rice was the only Catholic pro-life activist who took a position consistently in favor of protecting life, including unborn life, in all circumstances even when doing so would run counter to saving the mother or where the pregnancy was the result of rape.

Father Hesburgh never steered the inquiry to his favored position. And to preserve an atmosphere of friendly unity, Father Ted would step back with humility and characteristic deference. Indeed, Father Hesburgh's kindness extended to helping your author off the blooper roll. In the late 80s I hosted progressive Cardinal Joseph Bernardino of Chicago and Cardinal John O'Connor of New York, and with Father Ted also on stage behind me, I unceremoniously said it was the Center's pleasure to bring two of America's foremost theologians to the same stage. Laughter ensued, during which Ted leaned over to whisper: "you're all right professor, you didn't say which two."

Ted was a visionary who got things done, or occasionally, got fired. He encouraged all who joined with him to keep Notre Dame as that place where Catholics come to do their thinking. Father Ted linked academic and political venues in his personal life with ease, and he invited others like Ohio Governor John Gilligan to do the same. Gilligan did and nourished, along with Catholic scholar and distinguished theologian, Edward McGlynn Gaffney, the Center on Law & Government that had as its theme uniting law, ethics and public policy. With the election of Ronald Reagan, or as known by his film roll "the Gipper" playing all American George Gipp, politics changed a bit, and Father Ted permitted me in my more conservative moments to succeed John Gilligan.

These transitions were without rancor and indeed for many years to come, and at present, Centers brought law and government together for study (obviously much in need given the legislative impasse that has - again - shut down the government). Father Ted put the Center on Human Rights under the ever welcoming and building hand of the late Father Bill Lewers, C.S.C.s of fairness and a conscious objectivity, but that direction is irrelevant to the broader and enduring Catholic commitment to justice. Father Hesburgh was renowned for the challenge echoing Paul VI, "if you want peace, work for Justice."

In all of this, the proof is in the teaching, and if there was one commodity Notre Dame sought to supply on the campus itself, beyond a Ara Parseghian or Lou Holtz 11-0 season, it was inspiring, lasting, and provocative teaching.

My students will need to be the judge of mine. And just as every season is not without defeat, teaching isn't either, but at Notre Dame, neither teaching nor team will - God willing - ever fail as the result of complacency. The teaching principles of Frank O'Malley in liberal studies can continue to be found taped to the desks of new and tenured faculty, who never quite know when their students will permit their retirement. O'Malley is long-gone; Emil Hoffman no longer holds forth in chem, but in his time he could command a crowd in the tiered science lab or on the bench outside the old Knights of Columbus hall. The light-hearted nature of John Houck still resonates in a business program that seeks to awaken the world to the joy of giving as much or more than it receives.

And Notre Dame teaching extends well beyond the undergraduate or professional study years or even the regularly enrolled. Over my two decades at Notre Dame, I and others crisscrossed the continental USA visiting alumni clubs as a Hesburgh lectures. Not surprisingly, the university;s outreach to its alumni is not an unadorned outstretched hand for donations (and Father Ted's contributions to the endowment are what today are sustaining the momentum of Father Jenkins presidency, which on the heels of the quadrangle builder, Monk Malloy, delivers to current students a campus life experience that parents and older alumni envy for its beauty as well as practicality.

All of these Hesburgh-inspired achievements remain now to give honor to Our Lady. But one other aspect of Hesburgh's Notre Dame deserves note. It is well known that Notre Dame commencements are a venue for new U.S. Presidents to chart their course. Presidents as different as Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama have been likewise invited and treated.

While the practice of bringing heads of government to Notre Dame pre-dates Father Ted, it was sustained by him and applied specifically to newly elected U.S. Presidents in his usual fair-minded manner. It didn't matter to Father Hesburgh whether the President at the podium saw the issues as he or even as the Catholic Church did; what mattered was that the university both out of respect for the Office and in admiration for a fellow citizen making the personal sacrifice to take up public service, extended this important platform to a new President so that the world might listen, and so that the flagship Catholic university in America might thoughtfully respond.

Catholic in the upper case is denominational, and because that is so, we within this chosen boundary of faith will likely always have some objection to the policies of the woman or man electorally chosen as President of the United States. Father Ted in introduction and private remark was never known to be bashful in defense of the matters held especially dear to the Church or to himself. At the same time, the lower case sense of catholic as universal enjoined upon him extending tolerance and welcome for all.

In a hyper-partisan world, maintaining both usages of Catholic/catholic is not only difficult but also frequently confounding to our best supporters and even our family. Father Ted was immensely pleased that his successor, Father John I. Jenkins, C.S.C carried forth this tradition which lies at the very core of the university's reason for existence. Father Theodore M. Hesburgh,C.S.C left us a lasting legacy of what it means to be both Catholic and a University.