Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who set off homemade bombs at the Boston Marathon and embarked on a week-long police chase with his brother Tamerlan in April 2013, was sentenced to death on Friday.

The seven-woman, five-man jury that handed down Tsarnaev's sentence went against the wishes of several Boston bombing victims, including the parents of the attack's youngest victim, 8-year-old Martin Richard.

The jury's decision had to be unanimous in order for Tsarnaev to receive death; if one juror did not agree, a sentence of life without parole would have been imposed. Jurors in the case had to be "death qualified" -- willing, but not eager, to impose the death penalty.

Massachusetts outlawed capital punishment in 1982 and hadn't put anyone to death since 1947. (Tsarnaev was eligible for the death penalty because he faced federal charges.) A Boston Globe poll from April revealed that fewer than 20 percent of Massachusetts residents favored execution for Tsarnaev.

Setting aside Massachusetts' history with the death penalty or the wishes of those directly affected by Tsarnaev's brutal actions, there are a few other reasons why the death penalty deserves to be called into question.

We're likely putting innocent people to death.

Though Tsarneav pleaded not guilty to his crimes, his lawyer, Judy Clarke, was blunt about the fact that he did play a role in the 2013 attack. But almost 4 percent of U.S. capital punishment sentences are wrongful convictions, meaning about 1 in 25 people who are sentenced to death are likely innocent, according to a new statistical study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This could mean that approximately 120 of the roughly 3,000 inmates currently on death row in America might not be guilty, and at least several of the 1,320 people executed since 1977 were innocent.

Executions can be excruciatingly long affairs.

Oklahoma inmate Clayton Lockett was pronounced dead 45 minutes after his April 2014 execution began. The average length of the previous 19 executions in Oklahoma, prison officials told The Associated Press, was 6 to 12 minutes.

Due to complications with the lethal injection procedure, Lockett writhed and rolled his head back and forth on the gurney as the area around his injection site swelled to the size of a golf ball. He tried to speak and get up off the gurney until his heart rate weakened and eventually stopped altogether.

Lockett's not the only one to suffer on the gurney: On Jan. 16, Ohio executed convicted rapist and murderer Dennis McGuire by lethal injection with an untested combination of drugs including the sedative midazolam and the painkiller hydromorphone. It took him 25 minutes to die. In 2006, it took Joseph Lewis Clark, who was executed by lethal injection, 86 minutes to die.

Executions are often botched.

Amherst College law professor Austin Sarat examined every execution from 1890 to 2010 and found that 3 percent of all executions during those years did not go according to protocol. Though Sarat says these botched executions included decapitations at hangings and defendants catching fire in electric chairs, he also notes the percentage of executions not done properly hasn't gone down with the adoption of lethal injection.

"Botched executions have not disappeared since America has adopted the current state-of-the art method of lethal injection," Sarat wrote in a Boston Globe op-ed. "In fact, executions by lethal injection are botched at a higher rate than any of the other methods employed since the late 19th century, 7 percent."

An attempted execution in 2009 was so botched that inmate Romell Broom actually lived. Broom's execution was stopped after an execution team tried for two hours to find a suitable vein, sticking him with needles at least 18 times with pain so excruciating he cried and screamed.

Executions methods often cause physical pain.

Michael Lee Wilson, who was executed by lethal injection at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in January, told prison officials he could feel the combination of execution drugs injected just before his death.

"I feel my whole body burning," Wilson said before succumbing to the drugs.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice maintains a website devoted to executed offenders, which includes each inmate's last statement. Many of the statements contain phrases like "it's burning"; "I feel it"; "I'm feeling it"; "I can feel it, taste it"; and "this stuff stings."

"My left arm is killing me. It hurts bad," said Jonathan Green, executed in October 2012.

Sarat noted that pain may be inevitable in executions.

"A close look at executions in America suggests that despite our best efforts, pain and potential for error are inseparable from the process through which the state extinguishes life -- and that the conversation about capital punishment needs to take that fact into consideration," Sarat wrote.

Death penalty trials are expensive.

Death penalty trials can cost millions more than non-death-penalty trials -- a cost that's placed on taxpayers. The Economist reports:

An execution itself is not expensive, but the years of appeals that precede it are. Defendants facing death tend to have more, better and costlier lawyers. Death-row inmates are more expensive to incarcerate, too: they usually have their own cells, with meals brought to them and multiple guards present for every visit. “It’s because of this myth that these people will be executed in a couple of months,” explains Richard Dieter of the Death Penalty Information Centre.

Though Tsarnaev was sentenced Friday, he likely has years of appeals in his future -- meaning even more costs adding up.

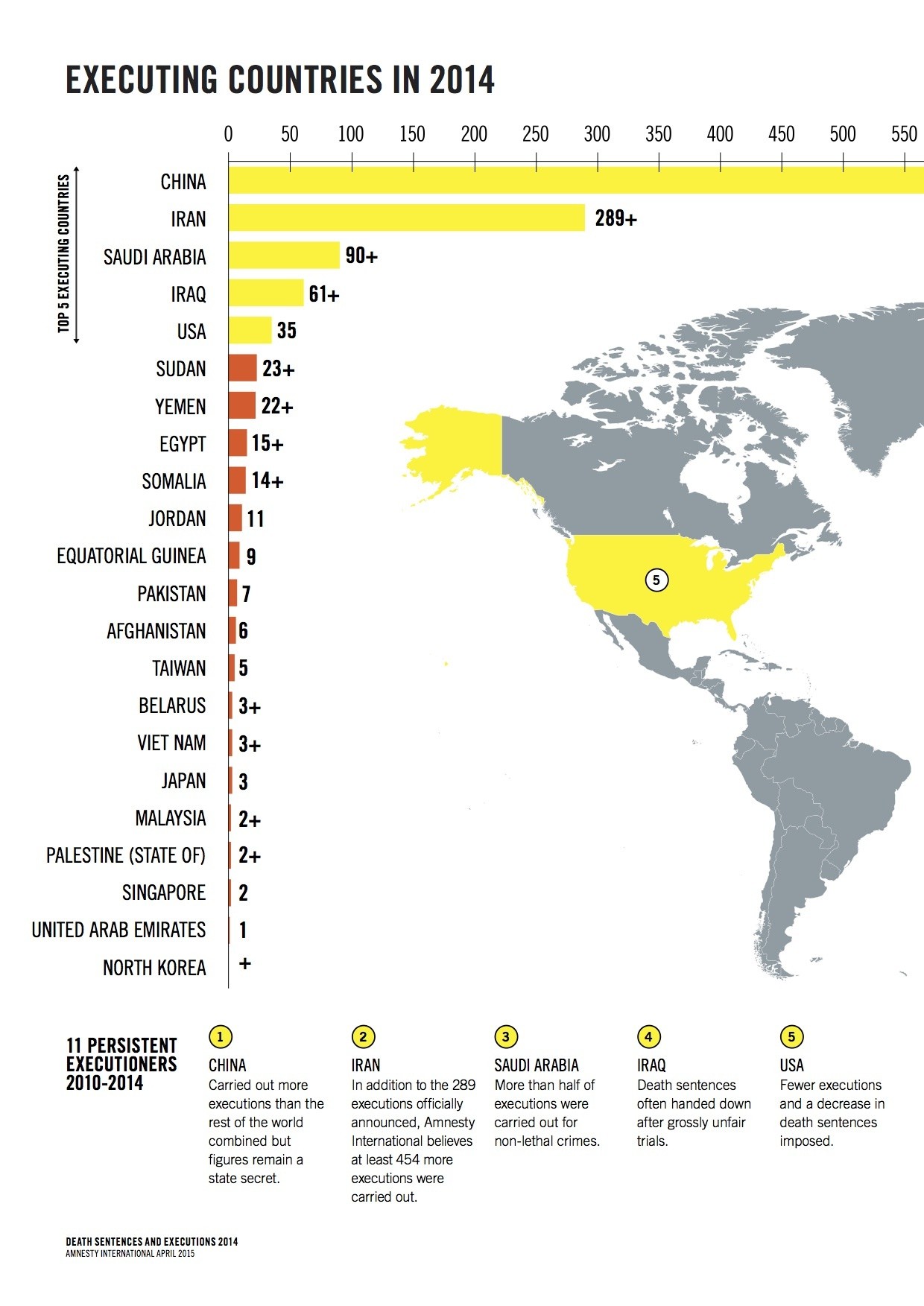

Very few countries perform executions, and we're in some questionable company with the ones that do.

The United States was one of 22 countries to report performing executions in 2014, and it is the only country in the Americas to have carried out executions that year, according to Amnesty International. Japan and the U.S. were the only countries in the G-8 to have carried out executions that year.

Steven W. Hawkins, executive director of Amnesty International USA, called Tsarnaev's sentencing "outrageous" in a statement Friday, saying it "is not justice."

"It is outrageous that the federal government imposes this cruel and inhuman punishment, particularly when the people of Massachusetts have abolished it in their state," he said. "As death sentences decline worldwide, no government can claim to be a leader in human rights when it sentences its prisoners to death."

We're considering lowering our standards for how to execute people, rather than re-considering the idea itself.

A short supply of lethal injection drugs has led states to consider other methods of execution, including the new drug combination that left Lockett writhing on the gurney in the execution chamber.

Aside from sedatives and heart-stopping drugs, some lawmakers are considering execution methods of the past, including firing squads, electrocutions and gas chambers. Missouri state Rep. Rick Brattin (R), who in January proposed firing squads as an option for executions in his state, said his suggestion wasn't an attempt to "time-warp."

"It's just that I foresee a problem, and I'm trying to come up with a solution that will be the most humane yet most economical for our state," Brattin said, noting he thought it unfair for relatives of murder victims to wait years, even decades, to see justice served.

Nick Wing contributed to this report.

A version of the story was originally published in April 2014, after the execution of Oklahoma inmate Clayton Lockett.

Before You Go